Author Ilan Stavans has three new books out this year, and will be introducing each one to Jewish Book Council readers as part of the Visiting Scribe series here on The ProsenPeople.

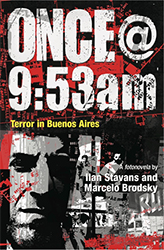

I want to describe how my fotonovela Once @ 9:53am: Terror in Buenos Aires came along. A version of these thoughts appear in the volume’s afterward, but I also want to respond to the controversy the experiment has generated.

I have always felt that the terrorist attack against the AMIA, the Jewish Community Center in Buenos Aires, on July 18, 1994, begged to be turned into a graphic novel. The effects of the tragic event in the ethnically mix neighborhood of Once in Buenos Aires, Argentina, are still felt today, especially among Latin American Jews.

Yet the idea didn’t materialize until I met Argentine activist and photographer Marcelo Brodsky and I met, around 2008, through a mutual friend. An admirer of his photographic work, particularly of his artistic strategies to “intervene” historical images in order to make their message more emblematic, I was eager to talk to Brodsky about my interest on the fotonovela as a popular genre in Latin America that needed to be appropriated in order to explore today’s politically-charged themes defining the region.

During lunch we discussed an assortment of topics, after which I asked him if he had read fotonovelas in his adolescence. I preceded my question by describing my own fascinating with the form, describing my assiduous readings of it almost every weekend, when new fotonovelas arrived to the corner newsstand in my neighborhood. I even told him that my father, a prominent actor of Mexican soap-operas, to make ends meet, had sometimes done some roles in fotonovelas.

As it happened, Brodsky was an enthusiast. A few days later, he even sent me a number of extra copies of Argentine fotonovelas in his personal collection by FedEx. That conversation — and a number of others we entertained in the next few weeks — showed not only how much we had in common but, also, that a collaboration between us was a possibility.

I remember mentioning to him my distress at the quagmire the AMIA investigation had become over the last fifteen years or so, and the extent to which I had become a buff of the whole terrorist incident, collecting a plethora of items in my library: photos, reportage, interviews, novels, books, documentaries, interviews, etc. I then suggested that through the format of the fotonovela, should we turn the 1994 incident into our central theme, we could achieve a multiple feat: explore through fiction — a type of fiction soundly based on facts — what journalism and police investigations had failed to uncover; renew the fotonovela as a legitimate genre of aesthetic exploration; and, equally important, collaborate in ways that would allow literature and photography to become partners, exploring ways in which words and images might work together.

I had another objective in mind: I wanted to use the fotonovela as a platform for innovative scholarship. This needs an explanation. Over my career, I have tried to approach research in non-traditional ways. I don’t like the term “creative” because traditional scholarship is creative too, yet I’m conscious that, in the Manichean paradigm used in academic circles, knowledge is often perceived along those extremes: conventional and unconventional. After the AMIA tragedy, and more so as the unfinished business of finding the culprits dragged on for a long time, I remember thinking to myself that the episode merited from me a more thorough exploration, although I didn’t know what format it should take.

My chance encounter with Brodsky made that possibility a reality. After all, he was an insider: an Argentine with some personal knowledge of the situation, since he had found large pieces of granite from the frontispiece of the AMIA building, lying beside the River Plate, in Memory Park, a memorial to the victims of State Terror he had helped build. These pieces later became part of Brodsky’s artwork. He got in touch with survivors in order to identify the stones and get their testimonies. It is while doing this kind of research that he became friends with people that were at the AMIA that fateful day. I instead was an outsider, albeit one with a long devotion to the incident.

The collaboration was pleasurable from beginning to end. During the next few months, I wrote a first draft. Actually, at that point the narrative I envisioned was more ambitious. It was divided into three symmetrical chapters, only the first of which deal directly with the AMIA bombing. The other two looked at different characters and plots in various parts of Buenos Aires as people struggled to make sense of the incident. We then secured funding from various foundations.

We set a date for me to travel for the shooting and began to make arrangements with actor’s unions, dressing companies, car and prop rentals, as well as with the AMIA administration. Our production headquarters were in the building of Hebráica, a Jewish club in the Once neighborhood. We also needed to secure permission from the Buenos Aires municipality to be on location. As we set the production in motion, it became obvious to us that the storyline as it currently stood was unwieldy. It would take years to shoot it and about five times the budget we had secured to finance it.

Reality always wins in these kinds of battles. The decision, at that point, was for me to trim it, focusing exclusively on the first chapter. My intention now was to make it cohesive, to allow it to grow organically. I subsequently made a revised draft that is quite close to the final version of the fotonovela. From that draft Brodsky commissioned a storyboard. During the production, that storyboard was simultaneously a map and a compass. It grounded us and gave us confidence.

The principal roles were played by professional Argentine and Brazilian Jewish actors. We persuaded family and friends to take some of the other roles. For instance, the girl carrying the balloons is Brodsky’s daughter; and one of the terrorists was a member of our crew. I personally wanted some prominent figures in the Jewish community to participate. This desire came from the movie My Mexican Shiva (2007), which was based on a short story of mine, in which the director cast my father and other prominent Mexican Jewish actors. He even invited me to the shooting and asked me to have a small nonspeaking part( due to union requirements), but it was ultimately cut. With that in mind, while in Buenos Aires I called my friend Marcelo Birmajer, author of the parody Three Musketeers, who is among the most celebrated Jewish writers from Latin America today. He has a cameo in the scene where the protagonist is beaten down. Brodsky is seen having coffee with the protagonist. I myself play the Orthodox rabbi that shows up inconspicuously with several colleagues in the early part of the fotonovela and at the end announces, apocalyptically, that the end of time has come.

I mapped out each page meticulously: the number of frames it needed, the location of text, and use of color. Brodsky used these instructions as inspiration, adapting them according to his aesthetic needs. Like in comics and graphic novels, the success of the fotonovela as a genre depends on the degree in which illustrations drive the plot forward while text goes deeper into character formation. Take pages 24 and 25, where a group of rabbis on the street in the Once neighborhood discuss an assortment of topics: the frame consistently look at them at once from afar and in close-up, allowing for gestural nuance, locating them in context, while their consuetudinary dialogue allows the reader to understand their mood, their demeanor, and what they are feeling in these crucial minutes before the terrorist attack. Or else, look at the chase sequence on pages 47 and 48, as the complicit girl runs toward the white Renault Traffic: the suspense strives from her matching with the other culprits while passersby become suspicious of their activities.

Since the post-1994 investigations have done nothing but hide them behind innuendoes, my explicit objective was to give the terrorist a face. I used the format of the fotonovela to give them a physicality they otherwise lacked.

Brodsky and I were always sure we wanted to conclude the story with the photograph of the tragedy used on the front page of major newspapers worldwide. Almost from the outset he worked on getting permission. I remember the moment he told me he had secured it. I felt as if the whole endeavor was now kosher. The aim was to delve into the way stereotypes are approached in the Argentine milieu, from the photographer’s gaze at femininity (as a freelancer he works for Playboy) to the representation of Jewish and Arab characters objectivized on the streets. This is the original context in which the action took place. Needless to say, each culture is comfortable in its own excesses.

Shooting took a total of three days. Brodsky took close to ten thousand pictures. In the months that followed he organized the material and began collaboration with a designer who developed the narrative while also inserting dialogic balloons and other comic-strip devices. Brodsky sent me periodically batches of about 5 or 6 pages, to which I made all sorts of changes, fine-tuning the dialogue, exploring alternative subplots, and so on. The need emerged of inserting maps of the city. For purposes of managing the suspense, we used digital clock-numbers on strategic pages.

The overall production took about eight months. The fotonovela was published in Spanish, in Buenos Aires, by the publishing house Asunto Impreso, whose editor Guido Indij made valuable editorial suggestions. On July, 18, 2011, in time to commemorate the anniversary of the incident, a photographic exhibit, with the storyboard, a handful of pages in various stages of development, and a video walk through the neighborhood, including interviews with the AMIA witnesses and survivors, was scheduled to accompany the release.

Ultimately, my dream was to use the very tools of popular culture in order to produce rigorous knowledge and to disseminate that knowledge in an alternative scholarly format. I wanted it to look like a comic yet deliver a serious message about the intersection of politics and religious freedom in Latin America. I wanted to amuse and stimulate, to provoke thought and generate discussion. Mostly, I wanted to reach a diverse audience beyond the Ivory Tower.

I was thrilled when Brodsky told me, by phone, that Once @ 9:53am: Terror in Buenos Aires was being read in Argentina by people of all backgrounds, some of whom had little previous information of either antisemitism and the terrorist attack. He also mentioned the heated reaction it generated in intellectual circles, including Jewish-Latin American ones, for turning tragedy into an illustrated narrative, as if embracing the topic through popular culture was a form of desecration.

I was thrilled when Brodsky told me, by phone, that Once @ 9:53am: Terror in Buenos Aires was being read in Argentina by people of all backgrounds, some of whom had little previous information of either antisemitism and the terrorist attack. He also mentioned the heated reaction it generated in intellectual circles, including Jewish-Latin American ones, for turning tragedy into an illustrated narrative, as if embracing the topic through popular culture was a form of desecration.

My response: it is precisely in the realm of popular culture where this fight needs to be fought, subverting predictable tropes, turning stereotypes upside down, and showing that art isn’t the exclusive domain of elites. After all, neither terror nor antisemitism are the prevue of only a few.

Ilan Stavans is a Lewis-Sebring Professor in Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College and the author of many books of both Jewish and nonsectarian interests.

Related Content:

- Amalia Safran: AMIA: Three Weeks’ Reflection

- Book Cover of the Week: Hot Dog Taste Test by Lisa Hanawalt

- Jeremy Dauber: If You Read Just 10 Stories by Sholem Aleichem…

Ilan Stavans is the publisher of Restless Books and a passionate lover of dictionaries, with a collection of over three hundred now housed in his personal collection at the University of Pennsylvania. He has published an assortment of books about language, including Spanglish: The Making of a New American Language (2003), Dictionary Days: A Defining Passion (2005), Resurrecting Hebrew (2008), and How Yiddish Changed America and How America Changed Yiddish (2020). He serves as a consultant to the Oxford English Dictionary and lives in Amherst, Mass.