In a tight, gripping tale, photographer and writer Julian Voloj and artist Claudia Ahlering beautifully weave together seemingly disparate subjects that are seldom found joined in a graphic novel. Ghetto Brother: Warrior to Peacemaker is the story of gangs, the power of unity, and the genesis of hip-hop in New York; it is the story of a secret Jewish heritage that comes to light; it is the story of the still-unfolding legacy of urban renewal and disenfranchised neighborhoods in the ‘60s and ‘70s in New York. It is the story of Benji Melendez, son of Puerto Rican immigrants who settled on the shores of the United States to pursue a better life for their family.

As a teenager in the South Bronx during a devastating period largely born of mass disinvestment, Benji finds himself seeking identity and social order through the world of gangs. But when violence escalates and peaks with the tragic death of one of Benji’s gang brothers, there is a hopeful, unexpected turn. The Ghetto Brothers call for peace in what culminates in the historic Hoe Street truce meeting instead of retaliating with the same brutality that took one of their own. It is then that area gangs apply their energy into what would become the emergence of hip-hop. Benji, however, finds himself transitioning into fatherhood and a career in social work while embarking on a personal odyssey that uncovers his crypto-Jewish heritage.

Ghetto Brother’s format as a graphic novel does justice to its powerful story. Claudia Ahlering’s clear black-and-white artwork elevates what could have been sentimentality into cinematic focus, and Julian Voloj’s voice feels authentic, purposeful, and nimble. Moreover, the contribution of each artist’s work delivers an emotional impact that is faster and stronger than traditional prose. Voloj and Ahlering give us a story for reexamining our lives and creating a better future

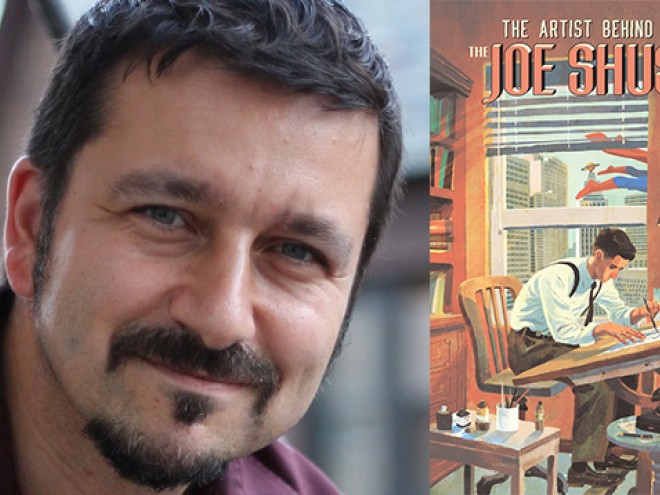

Interview with Julian Voloj

The graphic novel Ghetto Brother: Warrior to Peacemaker was inspired by the real-life story of Benjy Melendez, former gang leader who initiated a gang truce, fostered the development of hip-hop, and simultaneously discovered his Jewish roots. Author Julian Voloj shares the details of his creative process and how his own background helped him to understand his protagonist. See review on page 40, and read the unabridged interview online.

Rachel Pinnelas: How did you come to meet Mr. Melendez? Did you seek him out? Was it by chance?

Julian Voloj: My background is in photography, and I have always loved graphic novels. I did a series on Jewish diversity, so every time I found an interesting personality in New York, I always try to photograph the person. I read a profile of Melendez in Tablet: he’s a marrano Jew who was with a gang in New York. I was very interested in meeting him, so I asked the journalist to put me in touch.

I met with him in the South Bronx. I knew the area very well from my first solo exhibition, Forgotten Heritage, but I didn’t know the gang history there. Melendez told me his story, which I wanted to encapsulate in a single photograph for my project. He’s a character, as you can imagine from reading the book, and as we chatted I decided I really wanted to do more with this story. Initially I did a fumetti, which is like photo comics. But I thought there was so much more to this story and I saw a full movie, in a way. I connected at that point with an old friend of mine who did illustration for a book I did back in the nineties. She worked in television, but had never done a graphic novel. And so I put one and one together and said, “You know what? I have this idea. Would you be interested in doing a graphic novel?”

I really believed in the story so I said, “You know, worst case scenario, I do a Kickstarter. I will find a way to publish it.” I met Melendez back in 2010, and 2011 was the fortieth anniversary of the gang truce he had facilitated as a Ghetto Brother. So I said, “Listen Benji, you have all these contacts. Can you get to these people and maybe we can organize a reunion?” And so until the reunion, it wasn’t really clear if we could get this done. We only had maybe eight pages illustrated, but it was a very exciting concept, and at the reunion all these people who had been involved in the Hoe Avenue peace meeting were so gratified that someone cared about it — even this white Jewish guy from Germany! They all followed up afterwards with their own photographs and to share their stories, and suddenly we had all these materials for the graphic novel. From that moment on, I knew it was going to happen.

RP: Is there anything about your own personal history that you related to in Mr. Melendez’s?

JV: So much of his life has been engaged in the struggle to find his own identity, and I grew up Jewish in Germany, which has its own complexities. There were certain aspects where I tried to find of my own identity so I can identify with this whole coming-of-age challenge. But also in the Latino aspect, and the Jewish aspect. He’s also a people person; I consider myself a people person, but we’re very different of course. So it’s like, very different circumstances. But also, I feel like the sanitized New York we live in today has a lot to do with interest in this book. New York is now so clean and so corporate and so chain store-ish.

RP: What sparked your interest in the history?

JV: I have always been interested in the history of New York, and of the Bronx, especially. In 2006 I had my first solo exhibition, Forgotten Heritage, at the Bronfman Center in New York, showcasing photographs from a Jewish neighborhood if the Bronx. I explored and studied the history of the area for this project, so I very much consider myself a history buff. I also come from an educational background, so I wanted to educate but still make it entertaining. Visitors to the exhibition responded that they had learned a lot from it, which is exactly what I wanted to do: teach people on a historical subject without making it boring.

RP: As a photographer, what was it like working in another form of visual narrative?

JV: In a way, it was really like doing a movie — without having to deal with all the costs and such. We really recreated the Bronx. It was great that there were people like Joe Conzo — the first hip hop photographer, owing to the fact that he was the only one with a camera in his community at that time. Conzo gave us some of his photographs. So we took photographs, from which we created all of these whole landscapes for the book. It’s wonderful to see that: those years that you have been your head. Unfortunately, I’m not as talented as an illustrator, so I have to rely on other people, but I’m a storyteller, so it worked very nicely that we could get this together.

RP: A lot of people equate graphic novels with their colorful comic book counterparts, but Ghetto Brother is in black-and-white. Can you tell me about that choice?

JV: I envisioned it in that way to capture the retrospective quality of the story. When you have movies about World War II, they are often filmed in black-and-white. If you see a color image from the period it looks weird somehow, though of course in reality everything was in color. When I thought of this situation in the Bronx that was so, so dark, I felt like black-and-white would show a little bit of the desperation from this time. In a way it also symbolizes the way gangs saw each other in black-and-white terms: you’re either with me or against me. Interestingly enough, when we were looking for a publisher, some people really said they didn’t like the illustration because it’s very non-American. It’s very European in that sense. American publishers wanted it in color; they wanted it to more closely resemble The Warriors, because they thought it would be more marketable the more similar it was to a popular movie. But we were very happy with the images as they were.

RP: As an artist yourself, what was it like collaborating with another artist? And as a writer?

JV: It was a very interesting experience. It was also perfect timing, because I think the way we worked on this would have not worked ten years ago. I think I often drove the artist crazy because I continued to get input from Bronx locals who lived in this time and wanted to make sure the book was very authentic, very real. For me it was very important to have every detail right. So the illustrator and I were on Skype, phone calls, and email together constantly. The process took a lot of negotiation because I had certain things in my mind, and the illustrator had other things in her mind.

A great example is how we dealt with list of all the gangs who participated in this Hoe Avenue peace meeting. We were not sure if this list is complete or not, or how to best represent the list in a graphic novel. We came up with the idea to show the gang jackets, and ended up “listing” the participating gangs that way. It’s basically the first full page of the whole story. We did an event at the Bronx Museum, and several people in the audience were wearing their gang jackets. They came away really impressed at how accurately and realistically we had captured not just the story by the visuals with it, and that made all the difficulties and details of project worth it — even driving everybody involved crazy along the way.

Rachel Pinnelas is an Associate Editor at Dynamite Entertainment. A comic fan from a young age, she started her professional career in the industry as a Marvel intern, and has worked for both Marvel and DC Comics. She lives, reads, and writes in New York City.