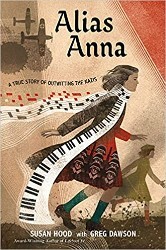

In the author’s note that introduces Harboring Hope, Susan Hood explains that this historical novel-in-verse will tell the story of the Danish Jews’ “escape” rather than “rescue” from the Nazis.

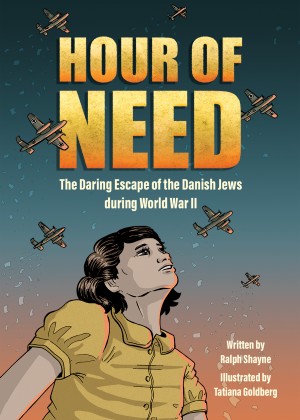

The German occupation of Denmark was calculated to function efficiently: if Danes cooperated economically with the Nazi regime, they would be subject to fewer restrictions than other defeated nations. Despite this fact, the Danish Jewish community was unique in Europe in that it largely survived the war. Allegedly, some German soldiers outright avoided violence, fearing that if they provoked reprisals they might be stationed elsewhere under harsher circumstances. Many Danish Christians also refused to collaborate with the Nazis. One theory holds that this was because the Jewish population was small and thoroughly assimilated, making it more likely that their fellow Danes would protect them.

The book’s protagonist is Henny Sinding, a young woman who actively resisted Nazism and helped bring many Jews to freedom. Working with other Danes who were committed to protecting their Jewish neighbors, she arranged for the Gerda III, a lighthouse supply ship, to transport refugees to Sweden. Although this complex story does portray imperiled Jews as individuals with agency, it inevitably focuses on the choices of Danish Christians, who could have acquiesced to Nazi laws but courageously chose a different path.

Sinding, like many of her fellow resisters, refused to see her actions as remarkable. Hood contrasts Sinding’s modesty with the reality that she routinely risked her own life. The daughter of a Danish naval officer, Sinding was familiar with maritime life and would use her knowledge to challenge authority. However, there was nothing inevitable about the course she eventually took. Her parents emphasized honesty and independence, yet they also thwarted her pursuit of a career in dance, viewing ballerinas as inherently corrupt women. Hood weaves in a number of Danish cultural influences, including Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales, Pippi Longstocking, and the Danish legend of Holger Danske, a sleeping knight who would awaken and come to the country’s aid.

Hood points out that despite the altruism of people like Sinding, not all Christian Danes had selfless motives. The vaunted bravery of the citizens who rowed Jews to safety in fishing boats appears in a different light once readers learn that many were paid, sometimes exorbitant fees, for their efforts. Hood’s commitment to telling the truth sets the book apart from other, more romanticized accounts.

In a section entitled “So Many Lives, So Many Stories,” the author also demonstrates that Danish Jews were not a monolithic group, but rather represented every niche in society: “Some were landowners,/suddenly homeless,/Some were executives,/suddenly unemployed./Some were shopkeepers,/suddenly out of business./Some were schoolchildren,/suddenly dismissed.”

Hood uses a variety of poetic forms in her exploration of the anomalous response of these Danes during World War II. Many of the poems are written in free verse, while others take the form of cinquains, nonets, and triolets. One concrete poem is shaped like a lighthouse, and list poems provide drama in a compact form.

The heroic acts of Henny Sinding and her colleagues — as well as the resilience of Denmark’s embattled Jews — present possibilities for defying authoritarian terror.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.