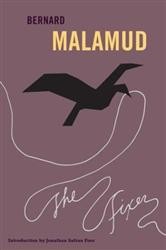

In the third and final volume of the Library of America’s collection of Bernard Malamud’s later stories and novels, editor Philip Davis invites us to consider Malamud’s current status as a figure in Jewish American literature and to address the question of why we should continue to read him today.

Many believe that Malamud’s achievement as a master of the short story dates from the late forties and early fifties, culminating with The Magic Barrel (1958), the first short story collection to win the National Book Award. His originality stems from his ability to compress language, a compression that mirrors the smallness of his immigrant father’s world. As critics at the time recognized, Malamud transformed the traditions of Jewish folklore into a terse yet deeply evocative Yiddish-cadenced prose that translated the heartache of Jewish history into feeling. Malamud is celebrated for his compassion, his evocation of a distinctive Jewish mood tinged with the tears of Jewish memory. As he explains in the Introduction to his Stories of Bernard Malamud (1983), which is included in this volume, “I would often be writing about Jews, in celebration and expiation.”

In addition to republishing thirteen of Malamud’s later stories, drawn mainly from the collection Rembrandt’s Hat (1973), the Library of America volume includes Malamud’s most provocative novel, The Tenants (1971), about Black-Jewish relations and the racial/ethnic sources of creativity itself. This volume also reprints Dubin’s Lives (1979), a book about a middle-aged biographer seeking a more erotically infused personal life, and God’s Grace (1982), a post-apocalyptic novel in the vein of Robinson Crusoe, featuring a Jew who seeks to instruct a tribe of chimpanzees in an ethical Jewish life.

The Tenants, embedded in the racial turbulence of late 1960s New York City, remains a significant work about the vexed story of Black-Jewish cultural history. Focusing on the charged relationship between two writers, one a non-Jewish Black man and the other a white Jewish man, Malamud meditates on empathy and the impossibility of racial brotherhood. His effort to conjure Black dialect is, a half-century later, embarrassing to read. While the novel ends with the familiar Malamud declaration that each “feels the anguish of the other,” followed by a chanting of rachmones (Yiddish for “mercy”), The Tenants ultimately exposes the limits of its author’s empathy.

Malamud’s lasting achievement remains the short story. In his best later stories, characters often reach a moment of illumination, of moral clarity, of rachmones, which confers a deeper humanity. We witness this modest but telling epiphany in “Rembrandt’s Hat.” Arkin, a minor art historian, and Rubin, a deep-feeling, self-doubting, struggling sculptor, have a falling-out over a comment by Arkin regarding a white hat Rubin is wearing; it reminds the art historian of a famous self-portrait by Rembrandt. Rubin feels “wounded” by this seemingly casual remark; it exposes his failure as an artist — “a fat burden,” he reflects, “on my soul.” In the end, Arkin apologizes, realizing that he has misremembered the particular Rembrandt painting he ascribed to Rubin. Rubin breaks down in tears, and each experiences a moment of catharsis.

One wonders if these late works, despite their familiar Malamudian themes, will garner a readership beyond Malamud scholars and students. Nevertheless, they invite readers to (re)discover this writer’s implicit moral challenge: that we recognize our connection to others. In Malamud, acts of empathy signal our humaneness. The greatest achievement is to be a mensch.

This last volume in the Library of America series may not showcase Malamud’s most revered, canonical early stories. But Malamud: Novels and Stories of the 1970s and 80s confirms his status as a profoundly important writer who was able to translate both his private grief and the fraught emotional world of Jewish experience into memorable literary art.

Donald Weber writes about Jewish American literature and popular culture. He divides his time between Brooklyn and Mohegan Lake, NY.