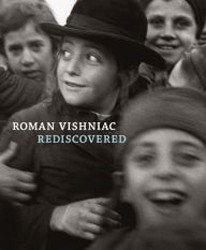

The Budapest-born Goldman was one of very few photojournalists working in Palestine in the 1940’s. Although he was largely unknown for most of his life — the norm at the time was not to publish photo credits — Goldman’s work nonetheless attracted a number of admirers, many of whom, such as David Rubinger, went on to become celebrated Israeli photographers themselves. His striking photographs, mostly depicting the day-to-day life of pre-state Israel, were never archived anywhere, but stored in simple plastic bags in Goldman’s apartment and serendipitously discovered, after the photographer’s death, by one of his friends.

Looking at Goldman’s work today, one understands instinctively why Goldman’s work was forgotten: There is something wonderfully un-modern about his work, a quality that appears sweet and naïve in today’s media culture, in which paparazzi lurk around every corner and the extreme close up is the favored aesthetic.

For one thing, Goldman never gets too close to his subjects. Unlike the generation of photojournalists who would follow him, Goldman, one senses, was too much of a gentleman to shove a lens in anyone’s face. Instead, he keeps his distance, and, as many of his subjects were Israel’s Founding Fathers — from David Ben Gurion to Menachem Begin — that distance translates perfectly into respect.

Here, for example, is Ben Gurion, shirtless in a black bathing suit, doing gymnastics on the Tel Aviv beach. Get too close and you run the risk of offending the leader or, even worse, of portraying him too flatteringly, as an icon of virility and strength, an outcome desired by the propagandist but reviled by the journalist. Get too far, and the magic of the moment — the elderly statesman frolicking— would be lost. Goldman, just a few steps away, strikes just the right distance.

This supreme sensitivity makes Goldman’s photographs a small miracle in today’s world of telephoto lenses and eliminated distance, and they make for interesting, almost prosaic constructions, rich with tensions between public and private.

But just as importantly, perhaps, and just as striking, is Goldman’s refusal to infuse the moment with metaphor, or embellish it in any other way. Unlike, say, the atmospheric shots of Henri Cartier Bresson, Goldman’s contemporary, Goldman is less interested in “the decisive moment,” that elusive fragment of time that captures both the instant and the timeless in one grand swoop. Rather, he is, as much as possible, an objective shooter, ever more the reporter than the artist, interested in beauty but never at the expense of his best estimation of the truth. His photographs, therefore, may not be as moving as Bresson’s, but they are instructive; anyone wishing to get a keen sense of what life in Palestine was like during the restive pre-state years is very likely to find it here, not in broad, inspiring strokes but rather in small, quiet and elegant works.

On a lighter note, the book showcases not only Goldman’s touching subtleties but also his impeccable timing: His photographs are a celebration of being in the right place at the right time, such as the King David Hotel shortly after it was bombed by Begin and his men.

The pictures go beyond telling the wordless story of Israel’s early years. They succeed, by straddling the line between journalism and art, in capturing the mindset and sensibilities of the young nation, a mindset that now looks so familiar yet so far away.