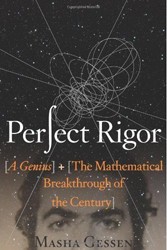

Welcome to Birobidzhan: “something between a fantasy and a joke … perhaps the worst good idea ever.” Thus award-winning journalist Masha Gessen describes the main subject of her book, Where the Jews Aren’t: The Sad and Absurd Story of Birobidzhan, Russia’s Jewish Autonomous Region. By her own admission, Gessen grew up with a Russian Jewish identity of “non-belonging.” Here she explores the story of Russian Jewishness through the lens of the fantastical, failed Yiddish state, searching for “Birobidzhan, the concept of home, and knowing when to leave.”

At the far east of Russia, by the Manchurian border, lies the land of Birobidzhan,which was declared a Jewish autonomous region in 1934, with Yiddish as its official language; the Soviet committee in charge envisioned a site for “the preservation of [The Jewish People’s] nationality.” It was designed as an agricultural colony, but the region’s distinguishing features were vicious mosquitoes, swamps, and rocky terrain. The farms soon flopped and were replaced with industrial plants. Early settlers were fleeing poverty and pogroms in the 1930s; by the 1940s, they were refugees of World War II. At its peak, Birobidzhan had six Yiddish-language schools, the Birobidzhan Star newspaper, and a library. But the vision was short-lived. Designated to accommodate minorities in post-revolutionary Russia and favored for the patriotic boost it gave during the war, it was condemned as the fuel of an “internal enemy” shortly afterwards. By 1948 the Jewish nationalist project was perceived as a threat. Stalinist purges cleansed the region of its activists, thousands of Yiddish books were burned, and Russification set in with full force. A Times correspondent visiting Birobidzhan in 1954 remarked simply, “I could not see that the place had any special Jewish character.”

Gessen’s book reports on Birobidzhan as a historical entity, but also inspects the “Jewish Autonomous Region” as an idea. Between shtetl and state, religion and regime, where do the Jews belong? What language does the Jew use to express the political, spiritual and cultural feeling of “home”? Zeev Jabotinsky and Theodor Herzl are discussed, but Gessen finds the answer in two other figures: historian Simon Dubnow (1860 – 1941) and poet David Bergelson (1884 – 1952). Dubnow, rejecting Zionism and socialism, argued that the Jewish people could domesticate diaspora: Judaism did not need a land, but a strong memory and multipolar community. Bergelson believed in a cultural Judaism expressed in Yiddish, and in Why I am in Favor of Birobidzhan (1935), he described the region as the place to “build a glorious Jewish culture, socialist in form and national in content.” Granted, this was a propaganda piece. More than a decade earlier, he had cursed the Bolsheviks. In two decades, he would disappear, accused of treason, on the Night of the Murdered Poets. Gessen highlights Dubnow’s ideology, contextualizing the dream of Jewish diasporic nationalism. Through Bergelson’s story, she presents the complexity of that dream for the Yiddish activist of the early twentieth century, desperate for survival — first, devastatingly, in Western Europe — and then, very soon, in the Soviet East.

Where the Jews Aren’t, though eloquently written and chronologically ordered, wanders as unexpectedly as its subjects, shifting dizzyingly from Dubnow to Bergelson to Birobidzhan and back. As Gessen explains, the book is best understood as a reflection on Russian Jewishness with Birobidzhan as its case study. Two forces charge the history of Birobidzhan. One is Jewish identity, a pulsing memory of the power of Yiddish prose and politics. The second is terror. Gessen stresses the importance of a “flight instinct”: “the suitcase, packed, is always by the door.” Gessen’s moves — from the Soviet Union to the U.S. to Russia and back — bookend the Birobidzhan story, becoming a contemporary frame for the cycles of fear and hope of Russian Jewry. Where the Jews Aren’t begins and ends with bags packed, ready for departure. But how lucky we are that Gessen takes the suitcase by the door and opens it: a glimpse of what is being taken along, and what is left behind.