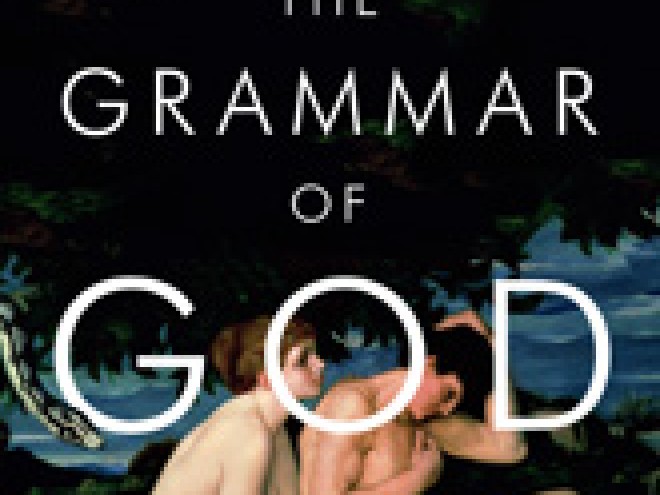

Earlier this week, Aviya Kushner wrote about the “smashing, positively dashing spectacle” of modern theater performed in Hebrew. She is the author of The Grammar of God and is blogging here all week for the Jewish Book Council’s Visiting Scribe series on The ProsenPeople.

In Monsey, New York, the religious Jewish community where I grew up, no one was reading The King James Bible. And I certainly wasn’t either.

My mother is Israeli, and so my first language was Hebrew; naturally, I read the Torah in Hebrew. At home, we often discussed the Torah around the dining-room table — its language, its humor, its grammar, and its tendency to contradict itself. At yeshiva day school, which I attended six days a week, the Torah and its commentaries were taught for hours each day. I memorized many passages, and was quizzed on others. I didn’t think I could be surprised by anything Biblical.

Then I drove a thousand miles, across the Mississippi River and through miles and miles of corn, and enrolled at the University of Iowa’s MFA program in creative writing. There, I took a Bible course with the novelist Marilynne Robinson. In that graduate course and in the community church class I attended, I encountered the Bible in English translation for the first time. And the translations I was reading obsessively weren’t just in English; they were also Christian.

It was an entirely new world, and I was often lost in it. On many occasions, I did not recognize passages I knew by heart in Hebrew. I found seven recurring surprises:

1. Verses in the Wrong Place. The verses, or psukim, are not always the same as they are in Hebrew. I first realized this when reading Job; a verse I was looking for was literally in a different chapter in English. But this really hit home with the Ten Commandments. One verse in Hebrew becomes four in The King James. The change in versification affects tone, but it also makes it hard to understand a lot of the commentators’ writing on the importance of adjacent words and ideas — because the location has been changed.

2. Headings, Titles, and Other Unexpected Explanatory Info. Reading the King James Bible, a Jewish reader might be surprised to encounter the heading “The Tenne Commandments.” Similar headings occur in other older influential translations, like The Geneva Bible and Tyndale’s Bible. For Jewish readers who may have spent hours poring over rabbinic commentary on which commandments count in the Ten Commandments, or what is commandment one, this heading can be jarring. Similarly, it’s strange to be told in a heading what a psalm is about.

3. Names Often Mean Nothing in Translation. In Hebrew, names are a big thing — laughter is part of the name Yitzchak (Isaac), and holding on to a heel is the source of the name Yaakov (Jacob). One strangeness of reading the Bible in English is realizing that names mean nothing in translation, because they are generally transliterated, not translated. So an English reader can’t hear a tie between Eve and life, or Adam and earth.

4. Body parts are sometimes erased or flattened. Looking for Moses saying that he is arel sfatayim, or literally uncircumcised of lips, and figuratively not up to the speaking aspect of leadership, in English translation? Good luck. The lips are sometimes edited out. So too is yerech Ya’akov, literally the thigh of Jacob, and other evocative bodily moments.

5. Punctuation can be jarring. There are no question marks in the Hebrew scroll, but there are plenty of them in English translation. Ditto for exclamation marks, periods, and colons. Sometimes punctuation can change the entire meaning of a passage, since there is a big difference between a declarative sentence and a question.

6. Grammar often evaporates in translation. Sometimes a verb becomes a noun, as in the infamous case of Moses with horns as opposed to his skin beaming with light. And sometimes, when there has been centuries of discussion on what is happening grammatically in a particular phrase, the translation picks one option — and the English reader has no idea how much of a challenge that phrase is.

7. Complexity doesn’t always come across. Difficult sections in Hebrew are often simpler and clearer in English. It’s interesting to think about whether it’s a good idea to translate ambiguity, or whether the translator’s job is to pick one meaning and go with it. Whatever the reasons, many of the passages that have stumped rabbinic commentators for centuries, and have created pages and pages of commentary, become easy-to-understand declarative sentences in English.

It is this definite, clear tone that I found most surprising of all. This tone gives the misleading impression that there is only one way to understand a text. Many English translations only translate the pshat, the simplest understanding of the Torah text itself, and do not translate commentary. The reader of English may not realize that there is a rich tradition of Hebrew commentary that is thousands of years old, and that there is a long lineage of argument and discussion. Instead, the English reader often encounters one single authoritative Biblical text, presented alone.

The final surprise for me was how I felt during this reading project. Reading translations of the Hebrew Bible into English was sometimes a sad experience; I was overwhelmed by all that had been lost. But I still recommend that Hebrew-speaking readers spend time with translations of the Bible, especially translations from different faiths and centuries.

The final surprise for me was how I felt during this reading project. Reading translations of the Hebrew Bible into English was sometimes a sad experience; I was overwhelmed by all that had been lost. But I still recommend that Hebrew-speaking readers spend time with translations of the Bible, especially translations from different faiths and centuries.

Why is it worth it?

The Bible in translation is the most important text in Western culture, and it can be dangerous to ignore it. Reading translations should be seen as a window into what millions of readers throughout the world think and feel; at the very least, whether we are Jewish or Christian, religious or secular, we should all be talking about how the particular Bible we read affects what we believe, and how language and translation have shaped us all.

Aviya Kushner is the author of The Grammar of God: A Journey into the Words and Worlds of the Bible, to be published September 8th by Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of Random House.

Related Content:

- Bible & Biblically Inspired Stories Reading List

- Jewish Essays on Language

- Jessica Cohen: The Hebrew Translator on Translation

Aviya Kushner is the author of The Grammar of God, which was a National Jewish Book Award Finalist, Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature Finalist, and one of Publishers’ Weekly’s Top 10 Religion Stories of the Year. An associate professor at Columbia College Chicago, she is The Forward’s language columnist and has a lifelong love of the Book of Isaiah.