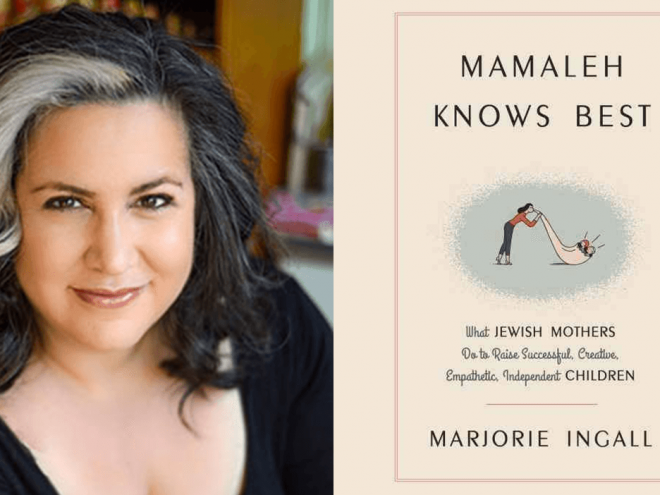

Marjorie Ingall is a columnist, ghostwriter, and author of Mamaleh Knows Best: What Jewish Mothers Do to Raise Successful, Creative, Empathetic, Independent Children. In honor of the book’s release tomorrow, Marjorie is guest blogging for Jewish Book Council all week as part of the Visiting Scribe series here on the The ProsenPeople.

I’m a ghostwriter. This week, a book comes out with my name on it—just mine. It’s the first book I have written as myself since 1998.

I feel naked.

To me, ghosting is infinitely more comfortable than writing a book as me. I love channelling someone else’s voice. It feels like a game. You talk to the person for as long as the person will let you (for some celebrities, that’s not long) and try to emulate their speech patterns and sense of humor. It’s wearing a Halloween costume, in book form! You treat the subject as a research project: find out as much as you can about their life so you can ask probing questions; try to make their story relevant to as many people as possible. Make them likeable, even if they’re not. (And let me head this off at the pass: No, I can’t tell you for whom I’ve written books, speeches, articles and blog posts, because then I’d have to kill you. That joke is never funny, but it’s really all one can say on the subject, non-disclosure agreements being what they are.)

Another reason I like ghosting so much is that I’ve spent so much of my career writing in the first person. I started in women’s magazines, which prize a confessional we’re-all-just-pals voice, perhaps as a way to seem unscary and sisterly. Even though I often wrote about health and science, I was still supposed to begin every story with a personal anecdote. It can feel both formulaic and invasive, putting yourself into a story where you really don’t belong. Getting to write a whole book and reveal nothing of myself was, in comparison, a huge relief.

Not everyone is so sanguine, though. When my older daughter was in first grade, I spoke to her class for Career Day. The teacher informed the class that Josie’s mom was a ghostwriter, and they got so excited they were almost vibrating. This was because they thought I wrote about translucent haunting spirits from beyond the grave. They were visibly disappointed to learn otherwise. One bright boy was more than disappointed – he was outraged. “So you wrote the book, but your name isn’t on the cover?” he sputtered. “That’s so unfair!” I explained that I got paid, and the arrangement was totally fine with me.

“But… it’s a lie!” he said. “People think someone else wrote the book, because it says someone else wrote the book, and you’re both lying!”

He wasn’t wrong. Most of us know that celebrities don’t write their own books, but we all participate in the fiction that they do. It’s a kind of collective self-hypnosis. Guess what: politicians don’t write their own op-eds or speeches, either. Though presumably after Melania Trump’s RNC debacle, more of us than a year ago know about the role of speechwriters in the performative, presentational game. (And presumably after Donald Trump’s original Art of the Deal ghostwriter publicly turned on him, more people understand how book ghosting works, too. For what it’s worth, I’m in a private support group for ghostwriters in which we talk about our projects and challenges, and most ghosts are utterly horrified by the notion of spilling the beans about clients. It’s akin to doctor-patient privilege. If you’re appalled by the client, don’t take the job.)

My new book, the one that I’ve written as me, is a book that combines social history, theology and parenting. It’s a look at the Jewish mother stereotype: a character that seems almost as malevolent to most of us as a ghostwriter does to a first grader.

But ghosting, I think, was oddly good practice for writing the book I did. An excellent ghostwriter encourages the best aspects of their client to shine through. The work of ghosting is self-effacing, but not self-negating; you need to be assertive to write the best book possible, and that means gently directing the client in the way they should go. The ghost also needs to be sure everyone — self, client, editor, and agent(s) — gets heard. If you’re going to be a good ghostwriter, you have to set up and manage expectations before you leap. You and the client both have to honor your commitments.

That’s what good parenting is, too. It’s not all about you; it’s about the next generation. (It’s planting seeds in a garden you never get to see, as Lin-Manuel Miranda wrote while pretending to be Alexander Hamilton.) It’s about being nurturing without being spineless. And despite the caricature of the Jewish mother as a neurotic, narcissistic, self-dramatizing human pressure cooker, the historical Jewish mother has done a tremendous job in raising kids who are both accomplished and kind.

Accomplished and kind is what we want to pretend our icons are, but it’s more important that we raise our real-life children that way in the real-life world.

Marjorie Ingall is a columnist for Tablet Magazine and a frequent contributor to The New York Times Book Review. She has written for many other magazines and newspapers, including The Forward (where she was The East Village Mamele), Real Simple, Ms., Food & Wine, Glamour, Self, and the late, lamented Sassy, where she was the senior writer and books editor.

Related Content:

- Beg, Borrow, Steal: A Writer’s Life by Michael Greenberg

- Amy Gottlieb: The Rabbi Whisperer Ponders the Sermon

- Judith Claire Mitchell: I’m Telling Everyone

Marjorie Ingall is the author of Mamaleh Knows Best: What Jewish Mothers Do to Raise Creative, Empathetic, Independent Children, and The Field Guide to North American Males. A former columnist for Tablet and the Forward, she is a frequent contributor to The New York Times Book Review and has written for a gazillion other outlets.