If ever there was a harsh reminder that Tu B’shvat is not a celebration of the spring, this year would be it. Just a few short weeks since Jerusalem was covered in snow, and only a matter of days since the Midwest regained function from its lake effect/severe weather storms; it’s a little difficult to picture almond blossoms swaying in a warm breeze by Thursday.

This is also my first year living in New York City, where that image is kind of difficult to picture in any weather. I won’t try.

Back in October, Gabi Gleichmann wrote a blog post for the Jewish Book Council that was so beautiful our own staff kept forwarding it around to one another: “A Jewish Family Tree: The Genesis of The Elixir of Immortality.” Reading Gleichmann’s description of what provoked him to write his first novel, I began to consider my own family tree.

Back in October, Gabi Gleichmann wrote a blog post for the Jewish Book Council that was so beautiful our own staff kept forwarding it around to one another: “A Jewish Family Tree: The Genesis of The Elixir of Immortality.” Reading Gleichmann’s description of what provoked him to write his first novel, I began to consider my own family tree.

My mother’s side has a tradition of re-mapping the entire family tree at every wedding. A long stretch of butcher paper is pinned up against a wall, blank but for the names of the furthest ancestors we can trace back, appropriately configured at the top of the sheet. From there, the wedding guests have to collaboratively produce the family tree. Over the course of the reception or rehearsal dinner, the map gradually materializes as relatives approach the makeshift board, remind themselves of the exact relation between themselves, the names already in ink, and the people standing around them, and scrawl their own names in. Parents write in their children; the bereaved their parents, grandparents, great-grandparents…

It’s a lovely tradition, and it’s always a moment of great pride. But Gleichmann’s writing sharply reminded me of how misshapen a result it must have produced at my parent’s wedding.

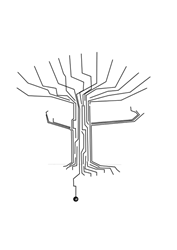

Most family trees meet laterally, with the subject’s parents’ legacies mapped across a horizontal plane; mine, to ride the metaphor, is the ever-widening trunk between the branches and the roots.

My mother’s family left the Russian empire late in the 19th century. They made a life for a couple generations in England, where one of our ancestors rose to some prominence as a rabbi — destitute, but revered — before emigrating to America and settling in the Midwest, later relocating to California.

My father’s family, on the other hand, was all but wiped out. Their (present-day) Belorussian and Romanian villages were easy and obvious targets of the Nazi genocide, and the few who had struck out for America by chance were left marooned in the Land of Opportunity, with no one left to send for.

So my mother’s family is tree branches, living, breathing, blossoming before our very eyes, while my father’s family anchors into the ground.

I know, of course, that tree roots grow, too. But because you can’t see them, because they’re buried, it’s difficult to recognize their true expanse or fully comprehend their effect on everything above-ground, crucial as we vaguely know them to be. I think it’s the same way with family legacies muted by the Holocaust: we are aware, vaguely, that the victims related to us existed, that they affected those who survived for us to know in some distant way, but we don’t have anywhere near a complete sense of what our families were before they all but ceased to exist. And we don’t understand how that loss poisons our lineage from there, not really.

I know, of course, that tree roots grow, too. But because you can’t see them, because they’re buried, it’s difficult to recognize their true expanse or fully comprehend their effect on everything above-ground, crucial as we vaguely know them to be. I think it’s the same way with family legacies muted by the Holocaust: we are aware, vaguely, that the victims related to us existed, that they affected those who survived for us to know in some distant way, but we don’t have anywhere near a complete sense of what our families were before they all but ceased to exist. And we don’t understand how that loss poisons our lineage from there, not really.

What stirred me in reading Gabi Gleichmann’s reckoning with his own absence of tangible ancestry was how he created something out of that loss, how he transformed this great void into something living and beautiful and sprawling for his children and on:

I told my wife I was determined to give our boys a present: a Jewish family tree, one that was even more extensive that the 350-year history of the Cappelen family. It would go back a thousand years. I would create it with my pen and my imagination. After all, the lives and undertakings of all those others were still alive within me. All of us are itinerant time machines; our recollections enable us constantly to travel back and forth in time, through our own lifetimes and throughout history as we summon bygone eras into our own present. The memories of the departed and the disappeared remain alive and well, pulsing beneath the surface of our own days.

I also reminded myself that only the art of the novel is capable of bringing back to life the dead and the forgotten, history’s myriads of anonymous individuals, by giving them faces once again and erecting a memorial over them.

He sees the roots.

Looking for Tu Bishvat reads? Try here.Nat Bernstein is the former Manager of Digital Content & Media, JBC Network Coordinator, and Contributing Editor at the Jewish Book Council and a graduate of Hampshire College.