Alina Bliumis received her BFA from the School of Visual Art in 1999 and a diploma from the Advanced Course in Visual Arts in Fondazione Antonio Ratti, Como, Italy in 2005, with visiting professor Alfredo Jaar. She is the co-author of the book From Selfie to Groupie and will be blogging here all week for the Jewish Book Council’s Visiting Scribe series.

When I moved from Minsk, Belarus, to New York 20 years ago, I noticed a certain ‘identity crisis’ within the Russian-Jewish community in the United States: Americans often consider members of this community to be Russian, Russians consider them to be Americans, and some Jewish Americans are not quite sure how to relate to this subset of their own community, still struggling to fit into the larger Jewish-American context. The question of how people define their own identity compelled my partner and collaborator Jeff Bliumis and I to undertake our artistic anthropological inquiry into Brooklyn’s Russian-Jewish immigrant population — we wanted to hear from people firsthand.

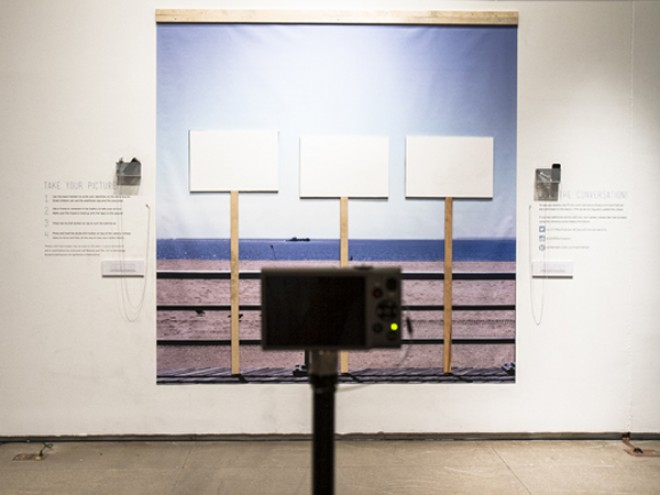

One morning, on a sunny July weekend in 2007, we drove to Brooklyn’s predominantly Jewish, Russian-speaking Brighton Beach to ask beachgoers to define their identities. Each participant was asked to pose for a photograph with any or all of three signs reading “Russian,” “Jewish,” and “American,” or to come up with his or her own self-definition by creating a unique sign with a marker and a paper pad.

We didn’t know what to expect. Would people be willing to interact? Would they feel comfortable publicly sharing their identity or be willing to be photographed, considering the history of Soviet Jews hiding they Jewish identity for decades?

We started at 6 in the morning, as we wanted to get a few shots of the three signs on a deserted beach. While we were photographing the signs, a seventy-something-year-old man named Alex walked by (from my experience in New York, passersby don’t usually get involved in other people’s business, but that rule doesn’t apply in Brighton Beach). The man stopped and asked “Chto vu zdes’ delaete?” (what are you doing here?). Again, anywhere else this question or the fact that he didn’t attempt to ask it in English might be strange but not in Brighton Beach. We explained that we were artists and told him about the project, asking him if he was willing to participate. He quickly replied “it is easy, I have an American passport, so I am American.” He took the “American” sign and posed.

We took his photo, and then as Alex was telling us his “immigration” story two more men, also in their seventies, walked by and asked: “Chto vu zdes’ delaete?” Once again we explained, and they both picked up all three identities and posed for a photograph. One of the men, Boris, explained “We are Jewish, we fought in the Russian army during Word War II, and we have American passports, so we chose all three signs.”

Alex wasn’t satisfied with Boris’s answer, though, and argued that once you move to a new country, you have to forget your past and move forward. Boris and his friend disagreed, and the conversation became more heated. At that moment we understood that it might be an interesting day ahead of us.

Each interaction took about 15 – 30 minutes: we introduced ourselves and our project, talked about where we came from, listened to where the participant(s) came from, talked about family history, occupation, interest, health, assimilation, political views, etc., and then we would finally, at the end of the conversation, we would ask them to participate and pose for a photograph. To our delight, most of the participants would say “yes,” although sometimes it took some persuasion. For example, one young women believed that it is bad “karma” to take a photo, so we explained to her that her voice (via the identification markers) was what mattered and she could cover her face, if she wanted. She did.

By 3 in the afternoon, 52 people had posed, and 44 portraits were taken.

And while the photos present part of the story, the explanations of the participants adds an additional level of nuance to the question of how one self-identifies. A few of these explanations can be found below:

“When I was living in the former Soviet Union, we had to hide the fact that we were Jewish. I wouldn’t want to make it public and talk about it openly. When my family moved to the USA and became citizens, I was able to say openly and proudly that I am an American Jew.”

“I am an American citizen but I don’t feel American. I like living here but I haven’t assimilated, didn’t learn the language well, and don’t have a deep understanding of American culture.”

“A writer is condemned to work with his own identity, shaped by language. In my particular case, Russian and English are the tools of this Soviet-born and American-raised author from Odessa.”

“In the Soviet Union, a ‘rootless cosmopolitan’ was someone who lacks patriotism and betrays his birthplace. They were wrong: a cosmopolitan is someone who believes that all people are equal, no matter where they come from.”

Find out more about this project and the companion book, From Selfie to Groupie, here. In NYC? You can participate in a pop-up version of this photography project at Jewish Book Council’s May 19th Unpacking the Book event, “Soviet Roots, American Branches.” Register here (it’s free!).

Related Content:

- A Replacement Life by Boris Fishman

- Panic in a Suitcase by Yelena Akhtiorskaya

- Reading List: Russian/Soviet Jewry

Alina Bliumis is a New York-based artist has been collaborating with her partner, Jeff, since 2000. Their works are in various private and public collections, including Moscow Museum of Modern Art, Museums of Bat-Yam, the Saatchi Collection, the Harvard Business School, the Museum of Immigration History, and the Victoria and Albert Museum.