It can be disorienting to imagine your favorite cartoonist’s works hanging in a museum. How do you preserve the intensely private and intimate experience of reading a graphic novel, for instance, when its individual pages have been posted on bright white museum walls?

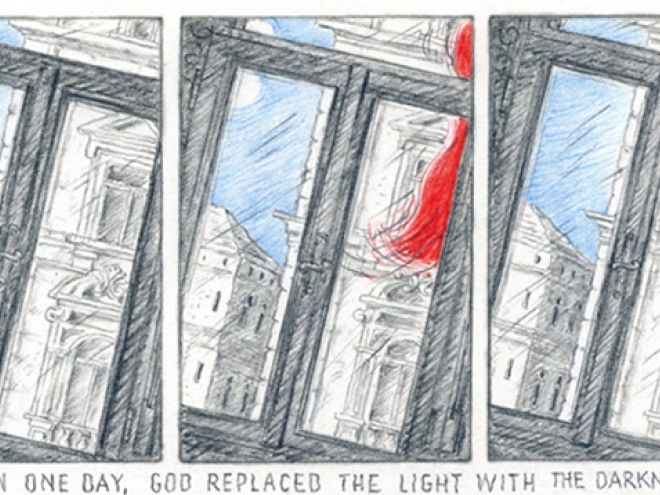

But as Vanessa Davis recently noted of the sprawling exhibition currently on display at The Jewish Museum, titled Art Spiegelman’s Co-Mix: A Retrospective, in this case the grouping, and in particular the section of the exhibition dedicated to Maus, “adds something that the book couldn’t do.” As she explained, the carefully mapped out pages of Spiegelman’s graphic memoir, now installed in perfect rows — sometimes alongside sketches, thumbnails, or other related media — visually evoke the timeline that the cartoonist worked so carefully to piece together in his memoir.

Davis’s observation opened a one-hour gallery talk that she gave to an audience of about thirty people last Thursday evening, which was part of an event series called “Writers and Artists Respond.” She recalled first reading Maus at twelve or thirteen years old, a time when, she said, “I saw my Jewish self and my artistic self as something different.” It took a while for her to recognize that you could be an artist who writes about your Jewish self without necessarily being relegated to the margins. “When you access your past, it’s bigger than you,” Davis later added, noting the tremendous influence that Spiegelman’s work — including but certainly not limited to Maus—has had on cartoonists and artists from all walks of life. She described Spiegelman’s work as “unsentimental, elegant, and serious” not despite but because he uses comics to tell stories.

Throughout the evening, Davis walked the group through the various parts of the exhibition, which includes works from Spiegelman’s early “underground” days to his New Yorker covers and books written for kids. She lingered over the famous and controversial New Yorker cover from 1992, of a Hasidic man kissing a black woman. When you’re creating a cartoon, she explained, unlike, for example, a photo-journalist, “you don’t have to be realistic.” Spiegelman’s work successfully captures small moments even as he touches on big events, allowing his readers to vicariously experience a “personal and immediate proximity” to whatever he’s addressing.

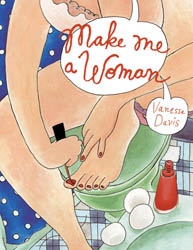

Davis’s own comics, which have been collected in Spaniel Rage (Buenaventura Press, 2005) and, more recently, the gorgeous, oversized hardcover titled Make Me a Woman (Drawn and Quarterly, 2010), tackle what she calls “my small life” — but her work, like Spiegelman’s, resonates beyond the particular moments and personalities that she portrays on the page. “That’s what comics is about — compartmentalizing,” she explained, describing the ways that Spiegelman manages to pack information into every inch of the page much like his father insisted on packing every article of clothing into an already overflowing suitcase. Davis too seems to have been influenced by this sentiment, though in a different way. “I like writing autobiographically and in small snippets,” she said at one point, referring in part to her diary comics.

Davis’s own comics, which have been collected in Spaniel Rage (Buenaventura Press, 2005) and, more recently, the gorgeous, oversized hardcover titled Make Me a Woman (Drawn and Quarterly, 2010), tackle what she calls “my small life” — but her work, like Spiegelman’s, resonates beyond the particular moments and personalities that she portrays on the page. “That’s what comics is about — compartmentalizing,” she explained, describing the ways that Spiegelman manages to pack information into every inch of the page much like his father insisted on packing every article of clothing into an already overflowing suitcase. Davis too seems to have been influenced by this sentiment, though in a different way. “I like writing autobiographically and in small snippets,” she said at one point, referring in part to her diary comics.

Viewing the exhibition with Davis as a thoughtful and inspiring guide reinforced the sense that seeing particular pieces of art on display can add depth to our understanding of them. There is a different kind of intimacy involved in weaving in and out of a crowd gathered to celebrate an artist and his works. It reminds you that your individual experience with a piece of art— of reading, or looking, or listening— is always, in fact, “bigger than you.”

Tahneer Oksman recently received her PhD in English Literature at the Graduate Center at CUNY. She is currently at work on a manuscript on Jewish women’s identity in contemporary graphic memoirs.

Tahneer Oksman is a writer, teacher, and scholar. She is the author of “How Come Boys Get to Keep Their Noses?”: Women and Jewish American Identity in Contemporary Graphic Memoirs (Columbia University Press, 2016), and the co-editor of The Comics of Julie Doucet and Gabrielle Bell: A Place Inside Yourself (University Press of Mississippi, 2019), which won the 2020 Comics Studies Society (CSS) Prize for Best Edited Collection. She is also co-editor of a multi-disciplinary Special Issue of Shofar: an Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies, titled “What’s Jewish About Death?” (March 2021). For more of her writing, you can visit tahneeroksman.com.