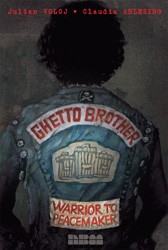

Earlier this week, Julian Voloj shared the story behind Ghetto Brother: Warrior to Peacemaker, his nonfiction graphic novel about the 1971 Hoe Avenue peace meeting brokered by the Ghetto Brothers’ president and Nuyorican crypto-Jew Benji Melendez. He will blogging here all week as part of the Visiting Scribe series on The ProsenPeople.

My graphic novel Ghetto Brother: Warrior to Peacemaker is many things. It’s a story about gangs in New York; a tale of the Bronx’ economic decline; a narrative of the early days of hip hop — but most of all, it’s a coming-of-age story with a Jewish twist.

As is well documented, the American comic book industry was full of Jewish pioneers. One might argue that only after Superman took off, the industry as we know it today was created.

As is well documented, the American comic book industry was full of Jewish pioneers. One might argue that only after Superman took off, the industry as we know it today was created.

Superman was, of course, the brainchild of two nice Jewish kids from Cleveland, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, who quickly learned how unfriendly the industry can be — the topic of my next graphic novel to be published in 2016. (Read a preview here.)

Superman, the Samson from Krypton, had his debut in 1938, the same year a nationwide pogrom in Germany called Kristallnacht made clear that Hitler’s hatred was not sheer rhetoric. The son of Kal-El stayed mostly out of politics, but prior to the United States’s entry into the war, Siegel and Shuster created one very cool mini-comic How Superman Would End The War, published in Look Magazine in 1940.

Probably the most iconic comic book attack on Hitler’s evil empire was the debut of Captain America, the patriotic avenger was created by another dynamic duo, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, in 1941. Kirby, arguably the most influential American comic book creator of the twentieth century, grew up on New York’s Lower East Side and changed his name from Jacob Kurtzberg.

After World War II, superheroes were in decline, and so was the comic book industry. Despite many Jewish creators, Jewish topics were rarely explored in comics. In 1955, EC Comics’s Impact ran an eight-page comic story by Bernard Krigstein called Master Race. The protagonist of the story was a former death camp commander who eluded justice until he was spotted on the subway by a Holocaust survivor. It’s a remarkable story, created less than a decade after the Shoah during a time when the topic was rarely discussed in popular media.

Decades later, Art Spiegelman started to publish Maus, which became the first graphic novel to win the Pulitzer. Spiegelman gave the medium the credibility to explore serious topics.

Since then, many Jewish artists have used the medium for a variety of Jewish topics from the relationship to Israel (Sarah Glidden’s How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less) to a comic book version of the The Book of Esther.

Comic books today are much more than just superheroes.

Born in Germany to Colombian parents, Julian Voloj is used to living in between worlds. In his work, the grandson of Shoah survivors explores questions of Jewish identity and heritage.

Related Content:

- Superman: The High-Flying History of America’s Most Enduring Hero by Larry Tye

- Superman Versus the Ku Klux Klan: The True Story of How the Iconic Superhero Battled the Men of Hate by Richard Bowers

- Reading List: Graphic Novels and Comics from a Jewish Perspective

- Essays by Artists, Illustrators, and Graphic Novelists on The ProsenPeople

- Super Boys: The Amazing Adventures of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster – The Creators of Superman by Brad Ricca

Julian Voloj is a New York – based writer whose work has been published in the New York Times, Rolling Stone, the Washington Post, and many other national and international publications. Born to Colombian parents in Germany, where he studied literature and linguistics, Voloj moved to New York in 2004. His fascination for forgotten heroes and hidden figures stems from his own family history and has been a leitmotif in his nonfiction graphic novels.