Photo by Toa Heftiba on Unsplash

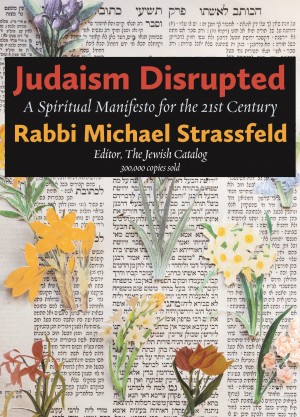

Fifty years ago, I, together with Richard Siegel z“l and Sharon Strassfeld, edited the Jewish Catalog: A Do-It-Yourself Kit. We hoped to show people how to shape their own Jewish lives with joy. We clearly hit a nerve. The Catalog’s timely and joyous spirit was embraced by the Jewish community and is still in print, having sold over 300,000 copies.

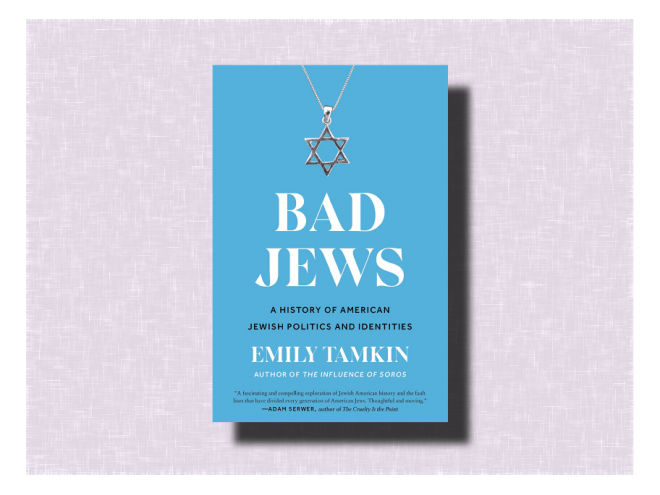

Judaism Disrupted: A Spiritual Manifesto for the 21st Century is my ninth book and has been the most original and most challenging book to write yet. In it, I attempt to answer a different question – not how to build a Jewish life but why. I wrote this book because I am worried about Judaism and its future. A few weeks ago, I was at a gallery in SoHo where a panel of artists talked about the intersection of art and Jewish life. Each of the panelists introduced themselves, one after another describing themselves as good, bad, or mediocre Jews. It was clear that all of them believed that a good Jew goes to synagogue, keeps kosher, and believes in God, which most of them did not. This discussion summarized what I see as a categorical mistake, one that led me to write Judaism Disrupted in the first place. Judaism’s purpose is not to help us become good Jews, it is to help us become good people. Judaism should be offering wisdom and practices to help us take the most precious gift we have been given — our lives — and live with meaning and purpose. For these artists, and so many others, Judaism’s rituals feel disconnected from anything that matters.

We live in very disruptive times. Almost 2000 years ago, there was another such moment, when the Temple in Jerusalem was destroyed by the Romans and the entire sacrificial system that was central to Jewish practice abruptly ended. The genius of the rabbinic leaders then was that they created a Judaism that was portable, that Jews could take with them wherever the winds of misfortune would carry them. Judaism emerged in a new form.

Today, we also need something different. In the open society in which we live (and thrive), we need a Judaism that is permeable. Seeing Judaism as permeable does not take away its distinctiveness but rather it opens the tradition to the world around us in new ways. Increasingly that world is not just neighbors or friends but people who are members of our family, be it through intermarriage or community ties.

Will Judaism change as a result? Of course it will, as it always has. Instead of viewing the outside world with suspicion, we now must have confidence in our tradition to interact with the world and retain our identity at the same time.

What does it mean to be a Jew in the twenty-first century? It means to be a mensch, striving to live with the awareness that we were strangers in Egypt and therefore we need to take care of those on the margins of society. Being a mensch requires that when we interact with family and friends, we recognize both that we are made in the image of God, and that we are all imperfect humans.

Judaism asks us to become spiritual menschen as well as menschen. What is the difference? Living with a spiritual perspective means that we understand that the world is larger than any one of us and that we are connected – to our planet, to God, or to the oneness/wholeness that underlies the universe.

In the open society in which we live (and thrive), we need a Judaism that is permeable.

Judaism isn’t only being disrupted by our times. It also disrupts us, challenging us to continue the unfolding creation of the world. How? My book outlines eleven core principles that can serve to help each of us to become a spiritual mensch. I suggest simple practices, some traditional and others brand new, to help us bring an awareness, a kavanah–intentionality – into our daily existence. They include the cultivation of inner qualities such as a gratitude for the blessings we have, compassion for fellow human beings in need, and finding a sense of satisfaction rather than an endless striving for what we think we lack.

In addition to ongoing daily practices, I explore the weekly practice of Shabbat, which enables us to take a break from our daily routine to rest and reflect. I delve into yearly Jewish holidays, which invite us to reflect on issues in our lives, for example, the meaning of freedom on Passover, the process of teshuvah–compassion, forgiveness and change – during the High Holidays, and the challenge of saving our planet on Sukkot.

Among the influences that have shaped my Jewish life, perhaps the most significant is Hasidism, the eighteenth century pietistic movement which teaches that holiness is not just found during prayer or studying Torah, but is found everywhere in the world. Any interaction can be a moment of holiness, of healing, of loving connection. For more than 3000 years, the Jewish people have engaged in a discussion of how to live a life of meaning. Over time, the meaning behind many rituals and practices has been lost and other old traditions are no longer appropriate to our time. It is up to us to continue to unroll the Torah scroll to find new meanings for the contemporary moment.

In my last chapter, “Final Words,” I write:

The last commandment, #613, is that each person should write a Torah scroll. These days this commandment is often fulfilled by paying a scribe to write one letter in a new Torah scroll on your behalf.

For me, a metaphorical understanding of this, the last commandment, is appropriate. In fact, we all write a Torah scroll — it is the story of our lives. We write it by our deeds and misdeeds. It is filled with hopes and disappointments. It is probably the only commandment that every Jew fulfills even if we do it without awareness. We leave the Torah we have written to family and friends to read and remember when we are gone. They provide comfort and ongoing connection to those who are no longer alive. These Torahs will be repeated as long as memories endure.

Rabbi Michael Strassfeld was one of the editors of The Jewish Catalog (1973) a guide to do-it-yourself Judaism that sold over 300,000 copies. He authored The Jewish Holidays (1985), co-authored A Night of Questions: A Passover Haggadah (1999) with his wife Rabbi Joy Levitt, and authored A Book of Life: Embracing Judaism as a Spiritual Practice (2002).