Photo by Pete Miller

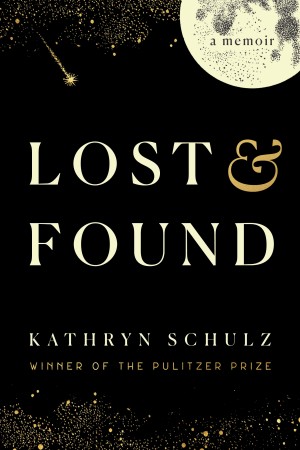

As a journalist, I make a living by telling the stories of other people: a forgotten African-American novelist, a Muslim immigrant to frontier Wyoming, a pair of female chefs operating a high-end restaurant in the middle of nowhere, Utah. So I suppose it’s not surprising that when I sat down to write a memoir, I found myself wanting to write not only about my own life but about the lives of those closest to me — in particular, my wife, whom I met in 2015, and my father, who died the following year. As that suggests, Lost & Found is partly a love story and partly an elegy, but it is also a consideration of all the many things, from the trivial to the momentous, that we lose and find over the course of a lifetime.

As it happens, my father’s own life exemplified both the tragic and the comic aspects of loss. Fluent in six languages and possessed of an astonishing intellect, he was the classic absent-minded professor figure, famous for constantly losing his wallet and cell phone and car keys (and occasionally losing his entire car). But, as I describe in the excerpt below, his earliest years were marked by loss in some of its most devastating forms, from exile to genocide. One of the central mysteries of his life — how such a loving and happy adult emerged from so much childhood trauma — is also one of the animating questions of my book: how, in the face of so much inevitable loss, can we find a way to live with gratitude and joy?

From Lost & Found:

I have sometimes thought that my father’s lifelong habit of misplacing things was the comic-opera version of the tragic series of losses that shaped his childhood. Although you wouldn’t have known it from his later years, which were characterized by abundance, or from his personality, which was characterized by ebullience, my father was born into a family, a culture, and a moment in history defined to an extraordinary degree by loss: loss of knowledge and identity, loss of money and resources and options, loss of homes and homelands and people.

In its broad outlines, the story is familiar, because it belongs to one of the most sweeping and horrific episodes of loss in modern history. My father’s mother, the youngest of eleven children, grew up on a shtetl outside Lodz, in central Poland — by the late 1930s, one of the most dangerous places to be Jewish on an entire continent increasingly dangerous to Jews. Because her family was too large and too poor for all of them to escape the coming war together, her parents arranged, by a private calculus unimaginable to me, to send their youngest child off to safety. That is how, when she was still a teenager, my paternal grandmother found herself more than twenty-five hundred miles from the only world she had ever known, living in Tel Aviv, which at the time was still part of Palestine, and married to a Polish Jew considerably her senior.

Not long after, my father was born, and not long after that, as a toddler, he was sent away to a kibbutz, to be raised for some years among strangers. While he was there, two formative losses befell his family. First, his biological father died and his mother remarried — a fact my father only learned more than two decades later, on his wedding night. Second, every member of my grandmother’s family that had remained behind in Poland was sent to Auschwitz. Her parents perished there, as did nine of her ten siblings. On January 27, 1945, when the camp was liberated, only her oldest sister, my great-aunt Edzia, walked out alive. I don’t know when or how this information reached my grandmother, or how she learned all the rest of the news that must have made its way to Tel Aviv name by name. Almost a quarter of a million Jews had lived in Lodz when she left it; barely more than nine thousand survived the war. When my father returned from the kibbutz a few years later, it was to a family reconfigured twice over, once by death and remarriage, once by the emotional and practical conditions created by this wholesale annihilation — almost an entire lineage gone, grandparents and aunts and uncles and cousins and friends and neighbors all slaughtered, a mother bereft beyond description.

Tel Aviv had been a relatively good place to weather the war, but it was not a good place to face its aftermath. With the future of the Middle East in flux, the city was increasingly dangerous; one morning, a friend of my father’s was killed by a stray bullet while playing in the street outside their apartment. As conditions deteriorated, the family, never well-off in the first place, struggled to scrape by. My grandfather was a plumber, but work was scarce, and by then he and my grandmother had two other sons to feed as well. In February of 1948, three months before the United Nations carved an entire new country out of Palestine, my grandparents decided that they were done trying to raise their children there. And so, in one of the more unlikely trajectories in the history of modern Judaism, they packed up their meager possessions, left what was about to become the state of Israel, and moved — to Germany.

It was, unsurprisingly, not their first choice. After the war, my grandparents had applied for visas to America, but there were few of those available and eleven million other refugees in need of a place to call home. Between the physical peril and their dwindling finances, they could not afford to wait indefinitely; and so, when my grandfather heard a rumor that it was possible to make a decent living on the black market in postwar Germany, he took notice. He had no religious devotion, no Zionist impulses, and no scruples whatsoever about bending the rule of law in the former Third Reich; his allegiance was to his family, and to survival. If a living could be made in Germany, then never mind that the whole tide of history was just then surging in the other direction: to Germany they would go.

It was a terrible journey. To get to a port with a ship bound for Europe, the family, together with an uncle who had decided to join them, had to travel by car from Tel Aviv to Haifa — a distance of just sixty miles, but hazardous ones, in those days. By then, civil war had broken out in Palestine between Arab nationalists and Jewish Zionists, and blockades, bombings, ambushes, land mines, and sniper fire were all increasingly common. Midway along the route, the uncle was shot in the front seat. My father, seven years old, sat in the back and watched while he gradually died. In later life, my father’s normal volubleness always veered around this tragedy; either from lingering trauma or out of an instinct to protect his children, he recounted it without elaboration, as bare biographical fact. I know only that his family, lacking any other option, continued on to Haifa, where they left the body, then sailed to Genoa and made their way to Germany.

They stayed for four years, settling in a little town in the Black Forest. My father played in the woods and learned to swim in the river and befriended an enormous sheepdog named Fix. At school, he mastered German, the language in which he first read Kidnapped and Treasure Island, and was sent by his teachers to sit alone in the hallway for an hour each afternoon during religious instruction. On evenings and weekends, his father set him down in the sidecar of his motorcycle and drove him all over the country, an adorable bright-eyed decoy atop a stash of Leica cameras and illicit American cigarettes. It was a pleasant existence, but also a precarious one, and the older my father got, the more he understood that his family was in trouble. The money they made was stashed under floorboards and rolled inside curtain rods; there was talk, not meant for the children to hear, of near misses and confrontations, of whether and where and how much the authorities had begun cracking down on smugglers. Over time, it became obvious to my father that his fate hinged on the question of whether the visas or the police would arrive first.

By luck, it was the visas: in 1952, my grandparents packed up their children, made their way to Bremen, and set sail for the United States. My father began throwing up while land was still in sight, and even if the ocean hadn’t been pitching beneath him, it is easy to imagine why he would have felt unstable. By then, he had lost, like Elizabeth Bishop, two cities and a continent, along with almost all of what should have been his family. He had lived on a commune and in a war zone, in the Middle East and in Europe, in the burning forge that made Israel and the cooling embers of the Third Reich. He was not yet twelve years old. He spent almost the entire voyage in his steerage-class berth, at sea in both senses, miserably ill. Only when his parents told him that they were drawing near to port did he struggle up to the deck to look at the view. That is my father’s first memory of his life in America: coming unsteadily into the sunlight and wind and seeing, there in the narrow waters off of Manhattan, the Statue of Liberty.

Kathryn Schulz is a staff writer at The New Yorker and the author of Being Wrong. She won a National Magazine Award and a Pulitzer Prize for The Really Big One, her article about seismic risk in the Pacific Northwest. Lost & Found grew out of Losing Streak, a New Yorker story that was anthologized in The Best American Essays. Her work has also appeared in The Best American Science and Nature Writing, The Best American Travel Writing, and The Best American Food Writing. A native of Ohio, she lives with her family on the Eastern Shore of Maryland.