Dr. Joanna Sliwa is a historian at the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (Claims Conference) in New York, where she also administers academic programs. She previously worked at the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, and at the Museum of Jewish Heritage — A Living Memorial to the Holocaust. She has taught Holocaust and Jewish history at Kean University and at Rutgers University and has served as a historical consultant and researcher, including for the PBS film In the Name of Their Mothers: The Story of Irena Sendler. Her first book, Jewish Childhood in Kraków: A Microhistory of the Holocaust won the 2020 Ernst Fraenkel Prize awarded by the Wiener Holocaust Library. She lives in Linden, New Jersey.

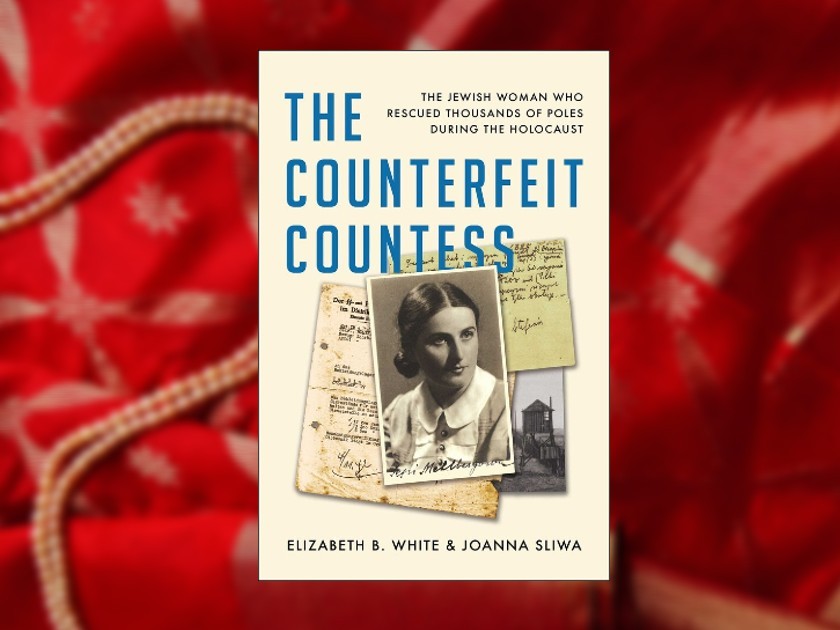

Jewish mathematician Janina Mehlberg survived the Holocaust in Poland by posing as the Christian Countess Suchodolska. As an official in the Polish Main Welfare Council (RGO) in Lublin, she won permission from the commandant of Majdanek concentration camp to provide food and medicines for thousands of non-Jewish Polish prisoners in the camp. As an officer in the underground Polish Home Army, she used the deliveries to smuggle supplies to resistance members imprisoned in Majdanek – a place where 63,000 Jews were murdered in gas chambers and shooting pits.

On her first delivery, Mehlberg met Dr. Stefania Perzanowska, the heroic organizer of the infirmary for Majdanek’s women prisoners. It was the start of a relationship that would prove profoundly meaningful to both women.

SS Captain Dr. Blancke had informed Perzanowska the day before that she was to take receipt of a special delivery for the women’s infirmary the next day. He warned her not to engage in any conversation beyond the minimum necessary to conduct the transaction. That morning, wanting to make a good impression when she received whatever was in the delivery, Perzanowska had put on the least filthy of her uniforms and kerchiefs and resolved to try to smile, if she could only remember how. It was almost a year since she had been arrested in Radom for Underground activities. After fifteen brutal interrogation sessions, the Gestapo gave up trying to extract information from her and dumped her in Majdanek in January 1943. Since then, the camp’s daily routine of unbearable suffering and unrelenting violence had steadily ground her down and drained her spirit. She tried to appear confident and caring to the desperately ill and dying women she could do so little to help, but in fact she felt almost devoid of human feeling, enclosed in a hard, cold shell of indifference.

As she approached the guardhouse, Perzanowska saw the trucks laden with cans and baskets and realized with a shock that this was the delivery she was to receive. Then she entered and saw a slender, handsome brunette with thick dark braids piled on her head like a crown. “Suchodolska of the RGO” Perzanowska heard the woman say. Somehow, her voice, her smile, her look of deep concern, and the warmth of her empathy penetrated Perzanowska’s shell and made her feel human again. The doctor stared in wonder at the woman as she read out the list of the food in the delivery and explained that the same delivery would be made twice a week and could include additional food and medicines as approved by the camp doctor. Here was someone, Perzanowska marveled, from that other world — “outside the wire” — that had come to seem a universe away. What efforts had been made, what risks taken to bring this largesse to the doomed? Perzanowska turned to the medical orderly and asked, “May I express the thanks of the prisoners to Madame?”

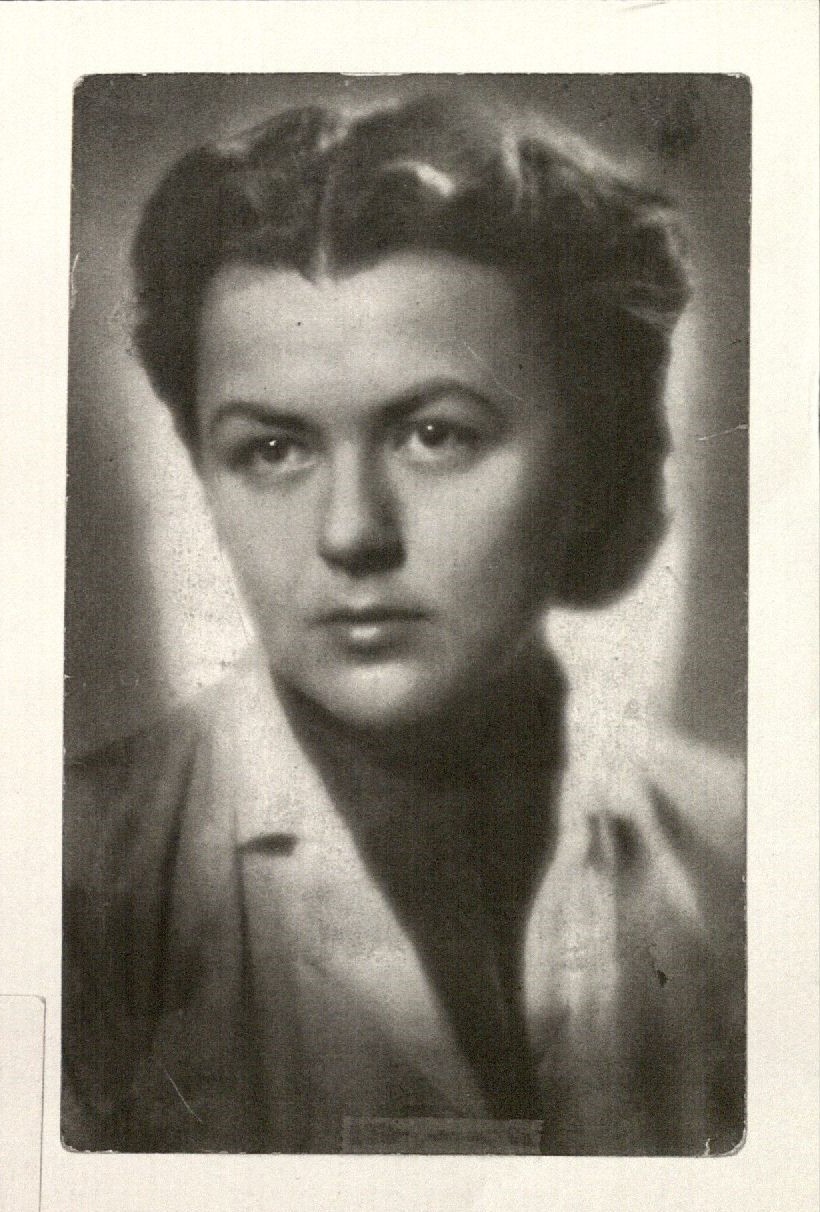

Janina Mehlberg, ca. 1930s.

“Janina’s Story,” Accession Number: 2003.333. Courtesy of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

The SS duty officer, having become bored as Janina read the list, was attending to other things. The medical orderly indicated to the women that they should step outside. They did so, then Perzanowska, fighting back tears, struggled to find the words to thank Janina. “You don’t know what it means to me to speak with you, a free woman. Everyone in Field I will be so grateful when I tell them what you have done, and so envious when they hear that I met with you!” Janina looked at the orderly. “Will you allow me to shake hands with the prisoner?” She showed him her palms. “You see I have nothing in my hands, I will not give her anything, just shake her hand.” The orderly looked around, saw no guard was watching, and said gruffly, “Shake hands, if you must, but make it fast!” Janina, tears on her cheeks and trembling, took Perzanowska’s hand, squeezed it, and said, “Tell the others in the compound that this handshake is for all of them, from all of us who are still free!”

Suddenly, SS guards spilled out of the guardhouse and sentry box screaming at Janina to finish and leave. Perzanowska watched in awe as Janina did not even flinch but calmly informed them in proper German that she was authorized to speak with the doctor about the needs of the infirmary, to learn the number of patients needing special diets, and to write down what was needed. Furthermore, as there were different kinds of soups and breads in the delivery, she needed to show the doctor where they were placed in the truck. So Janina and Perzanowska climbed onto one of the trucks, and as Janina announced which can had what kind of soup and explained what was in the baskets, she asked Perzanowska under her breath in Polish whether she wished to send a message to anyone. Perzanowska, feeling the guards’ eyes on her, gave a slight nod. Then Janina, notebook in hand, told the orderly that she had to take down the information of the persons who received the delivery. The oblivious orderly stated his name, while Perzanowska muttered an address in Lublin and a brief message to be sent there.

Finally, some SS men got in the trucks and drove them off to the protective custody camp. The officer of the day informed Janina that she was to pick up the cans outside the gate at 1:00 p.m. the next day. Then Janina watched as Perzanowska walked slowly back down the road to hell. It was a vision that would haunt her for days.

But Perzanowska was actually smiling. “There are brave people on the outside who are taking risks to help the helpless victims of Majdanek!” she thought with amazement. And she diagnosed the cause of the sensation that had just come upon her: hope.

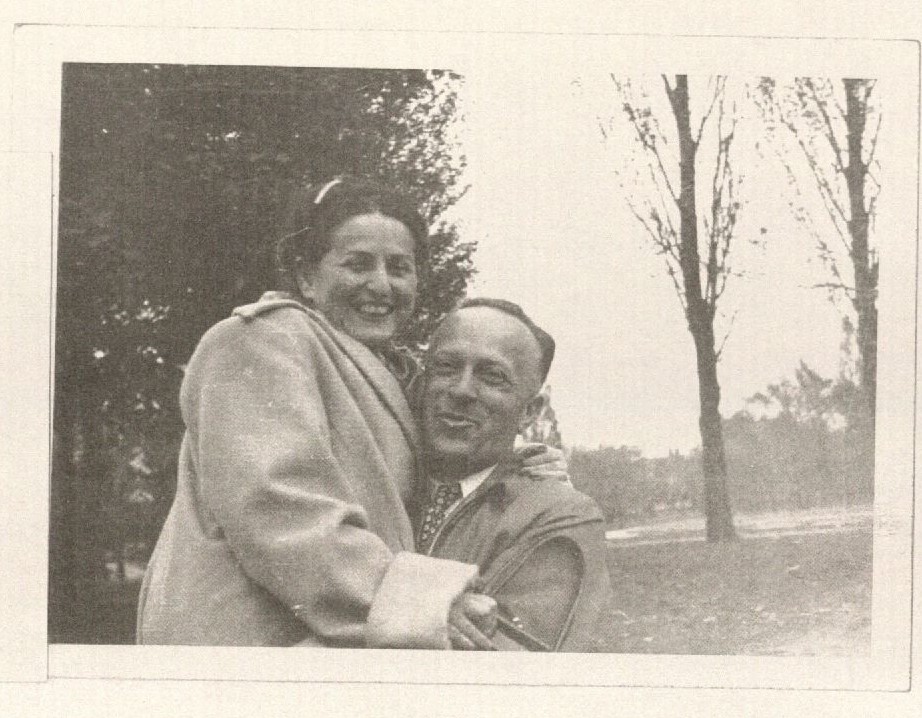

Photo of Janina and Henry Mehlberg, ca. 1950s.

“Janina’s Story,” USHMM Accession Number: 2003.333. Courtesy of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Dr. Elizabeth “Barry” White recently retired from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, where she served as historian and as Research Director for the USHMM’s Center for the Prevention of Genocide. Prior to working for the USHMM, Barry spent a career at the US Department of Justice working on investigations and prosecutions of Nazi criminals and other human rights violators. She served as deputy director and chief historian of the Office of Special Investigations and as deputy chief and chief historian of the Human Rights and Special Prosecutions Section. She lives in Falls Church, Virginia.