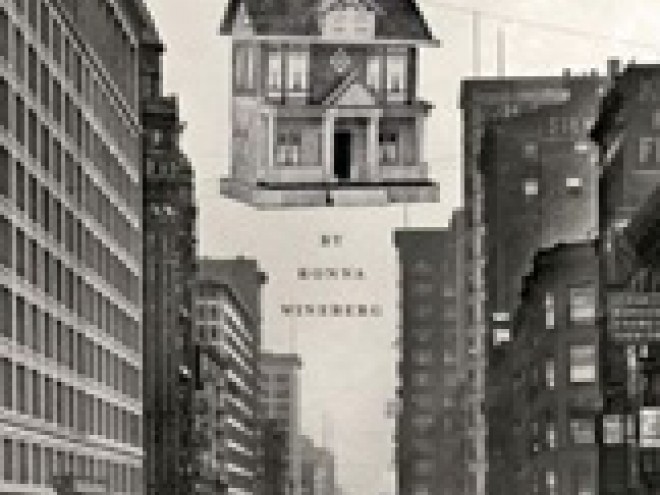

Earlier this week, Ronna Wineberg wrote about saying Kaddish for her mother and also shared a deleted scene from her first novel, On Bittersweet Place. She has been blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council’s Visiting Scribe series.

The Russian portions of On Bittersweet Place are loosely based on my family history.

The Russian portions of On Bittersweet Place are loosely based on my family history.

When I was growing up, though, I knew only the broad outlines of that history. My paternal grandparents came from Lithuania and met in Chicago. I knew very little about their lives. My grandfather had died when my father was seventeen. My grandmother didn’t speak about the past except to tell us that we were related to a great, intellectual family, The Katzenellenbogens, and to the teacher of Albert Einstein. She didn’t talk about her parents or siblings or life in Europe.

I knew more about my mother’s family. She was the first child born in America. Her parents, older siblings, aunts, and uncles all came Russia. Our small house was filled with visitors, relatives who spoke with thick accents. Though I’m a second generation American, I often felt as if I had a foot in each world then, the old and the new. My great grandfather had been murdered in a pogrom. I didn’t know how or when.

When I was in college, my cousins and I decided to talk to my mother’s family about Russia. We gathered relatives in the living room of my parents’ house and asked questions. We were riveted by stories of hardship, persecution, and flight. The discussions were passionate; people disagreed about the details of what had happened. My great uncle, a man in his late sixties, described his father’s murder in Russia. As he did, my uncle cried. That moment stayed with me.

I never learned more about my father’s family. I knew I was fortunate to have learned about my mother’s history. I knew, too, I wanted to write about an immigrant family in the 1920s. But I wrote short stories about other subjects, a collection of stories, Second Language.

Finally I went back to the family history. Writing On Bittersweet Place taught me how to use fact in order to create fiction. This is what I learned:

1. Family stories aren’t enough. I realized I didn’t know the history of the period. I did research about the world of 1912 to 1928 first. Questions arose as I wrote and revised. I had to do more research. Were matchbooks used in 1927? Yes, I discovered. Was “big shot” a phrase in 1927? No, I learned. The details needed to be right.

2. Facts can interfere with imagination. I began to write about life in Russia using the facts of my great grandfather’s death. This didn’t work. I decided I wanted to capture the emotion surrounding his death but not to duplicate the facts. This decision felt liberating. I created a new family and characters. When I discovered Lena’s voice, On Bittersweet Place developed a rhythm, a direction. Lena isn’t based on a real person. She led me through the book.

3. A novel begins with an idea: what if. Recently, I read from On Bittersweet Place at a synagogue. During the Q&A, an eighth grader asked, “How did Lena know she wanted to become an artist if she had never tried to draw?”

“Each person is different from the other,” I said, struck by the question. “One person wants to draw, another to swim, and another to sing. Do you ever get an idea that you want to try something you’ve never done before?” I asked.

“Oh, yes.” He nodded.

“That’s what happened with Lena and drawing. She just wanted to try it. Try to be an artist.”

I realized this is a description of writing a novel. A novel is an idea that comes to a writer. It may be based on a phrase, an image, a fact. The writer doesn’t know if he or she can actualize the idea. But the writer tries. As I wrote, I wondered: what if this happened or that happened. I experimented, surprised by the characters and plot twists.

4. Characters will guide the writer. Lena’s brother Simon pushed me to make him a more important character than I’d anticipated. Lena behaved in ways I didn’t expect when I began to write the book.

5. The writer needs time. All writing, especially a novel, needs time to percolate. I needed time to focus on the book in a consistent way. Since fiction isn’t bound by fact, scenes and characters can be re-imagined and rewritten in draft after draft. That’s one of the pleasures of writing. The author Paul Theroux has said, “Fiction gives us a second chance that life denies us.” Everything in a novel is open to change. Until the book is published. Then the characters and story fly away from the writer. The book takes on a life of its own.

Ronna Wineberg is the author of On Bittersweet Place and a debut collection, Second Language, which won the New Rivers Press Many Voices Project Literary Competition, and was the runner-up for the 2006 Reform Judaism Prize for Jewish Fiction. She is the recipient of a scholarship from the Bread Loaf Writers Conference and fellowships from the New York Foundation for the Arts and elsewhere. She is the founding fiction editor of Bellevue Literary Review, and lives in New York.

Related Content:

- Essays: On Writing, Publishing, and Promoting

- Reading List: Historical Fiction

- JBC Network Books 2014 – 2015