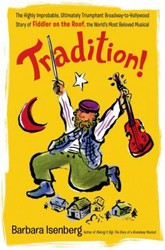

It has been fifty years since Fiddler on the Roof opened on Broadway on Tuesday, September 22, 1964 at New York City’s Imperial Theater. To mark its golden anniversary, two histories of the musical have recently been published. One is Alisa Solomon’s incisive, comprehensive, and scholarly Wonder of Wonders: A Cultural History of “Fiddler on the Roof” (2013); the other is Barbara Isenberg’s more popular and lightly researched Tradition! The Highly Improbable, Ultimately Triumphant Broadway-to-Hollywood Story of “Fiddler on the Roof” (2014). (Also valuable for students of the Fiddler phenomenon is Jeremy Dauber’s engrossing 2013 biography The Worlds of Sholem Aleichem: The Remarkable Life and Afterlife of the Man Who Created Tevye.) In the past half century Fiddler has attained a mythic status among American Jews. There are few adult American Jews who are unfamiliar with stage or cinematic portrayal of the tribulations of Tevye, Golda, and their three eldest daughters Tzeitel, Hodel, and Chava.

No one associated with Fiddler anticipated that the show would be a smash, and they would have been happy had it lasted a year. Previous (and later) Broadway shows with Jewish themes had been at best modestly successful, and few thought Fiddler would attract many gentile theater-goers. One potential producer turned it down because he believed its appeal would be limited to Hadassah theater parties. He couldn’t have been more wrong. Fiddler was one of the great successes in Broadway history, and its original backers made a fortune. Its eight-year run of 3,242 performances surpassed that of My Fair Lady, Oklahoma, and South Pacific, and until Grease came along in 1979 it held the record for the longest-running Broadway musical or non-musical show. There have been five Broadway revivals of the show, and every year at least five hundred productions of Fiddler are staged in the United States. In the 1960s and 1970s the musical was performed in Spanish, German, Hungarian, Czech, Turkish, Greek Swedish, Ukrainian, Russian, Hebrew, Yiddish, and other languages. The Japanese version became the longest-running American musical in Japan, and the British version played in the West End for four and a half years. The New York Times theater critic Clive Barnes gushed in 1967 that Fiddler, after only three years, had become “a living, breathing classic. To criticize it would be like criticizing motherhood, and, like motherhood, it’s here to stay.” Pauline Kael, the notoriously critical movie-reviewer, said the 1971 film of Fiddler, that year’s most financially successful movie, was “the most powerful movie musical ever made.”

Yet there were many people who, despite Barnes and Kael, disparaged Fiddler. Part of this stemmed from an elitist disdain for Broadway’s appeal to middle-brow tastes, and it certainly is true that Jerry Bock (music) and Sheldon Harnick (lyrics) were not in league with Verdi or Puccini. But criticism of the show, particularly by Jews, was motivated by more than cultural snobbishness. First of all there was the matter of historical accuracy. Jerome Robbins, the director of Fiddler, took great pains to portray Jewish life in Russia as truthfully as possible, transporting the cast to Orthodox weddings in New York City and providing them books on the history and sociology of Eastern European Jews. In the competition between historical verisimilitude and the demands of theater, however, the latter emerged victorious. Thus the matchmaker in Fiddler was a woman, but matchmakers of Fiddler’s era were men. No tailor would come to a Friday night Sabbath meal with a tape measure around his neck, nor would any rabbi dance with a woman. Neither the sets nor the characters ring true.

In his 1964 Commentary essay “Tevye on Broadway,” the Yiddish literary scholar Irving Howe described Fiddler as “gross,” “disheartening,” “a tasteless jumble of styles,” and “the cutest shtetl we’ve never had.” For Yiddish purists, Fiddler was a sacrilege, a reflection, to quote Howe, of the ignorance of American Jews of East European Jewish life and of “the spiritual anemia of Broadway and of the middle-class Jewish world which by now seems firmly linked to Broadway.” Howe was not alone. The novelist Philip Roth called Fiddler “shtetl kitsch,” and the writer Cynthia Ozick said it was “shund” (romantic vulgarization). Ironically, in 2002 YIVO presented Bock and Harnick with its Special Cultural Arts Award.

Then there is Fiddler‘s distortion of the eight Sholem Aleichem short stories upon which the musical was supposedly based. An example is the contrast between how Sholem Aleichem and Fiddler handled Chava’s conversion to Russian Orthodoxy and her intermarriage. Sholem Aleichem made clear that transgressing these ultimate Jewish taboos was unacceptable to Tevye’s world and that he would never forgive Chava. She is dead to him, and he and Golda sit shiva for her. When Tzeitel begs Tevye to show some pity toward Chava, he replies, “Don’t speak to me of pity. Where is her pity for me? She is not my daughter. My daughter died long ago.” Despite his love for Chava, traditionalism triumphs over universalism.

The message of the musical and movie, however, is different. Here Chava and her husband, Fyedka, come to see her family off after it has been expelled from the village. Tevye initially wants nothing to do with the couple, and Fyedka responds, “Some are driven away by edicts, and others by silence.” In other words, there is no fundamental difference between the anti-Semitism of the Czar and Tevye’s opposition to intermarriage. Tevye is moved by Fyedka’s words, and he acquiesces in the life the couple has chosen. “God be with you,” he says softly to them. Here Fiddler reflects the liberal sensibilities of Jerome Robbins and Joseph Stein, who wrote the musical’s book. Harry Stein, Joseph Stein’s son, said that his father did not object to his own marriage to a gentile, but he did regret that his son did not marry a black women since that would more clearly demonstrate the family’s liberal and integrationist bone fides.

Jewish survivalists strenuously objected to Fiddler’s take on the Chava story. Ruth Wisse, the Harvard Yiddish literary scholar, noted that “it must have felt perfectly innocent to change a Jewish classic into a liberal classic.… But if a Jewish work can only enter American culture by forfeiting its moral authority and its commitment to group survival, one has to wonder about the bargain that destroys the Jews with no applause.” Fiddler reflected the fundamental conflict within the liberalism of the 1960s between the celebration of ethnic and cultural pluralism on the one hand and the applauding of individual autonomy and the rejection of ethnic and religious divisions on the other. In esteeming Fiddler, American Jews were generally oblivious to the fact that they were being asked to simultaneously respect the values of Tevye while accepting the imperatives of the American melting pot. They have remained conflicted, and this tension has remained at the center of the debate over the nature of American Jewish identity.

Jewish survivalists strenuously objected to Fiddler’s take on the Chava story. Ruth Wisse, the Harvard Yiddish literary scholar, noted that “it must have felt perfectly innocent to change a Jewish classic into a liberal classic.… But if a Jewish work can only enter American culture by forfeiting its moral authority and its commitment to group survival, one has to wonder about the bargain that destroys the Jews with no applause.” Fiddler reflected the fundamental conflict within the liberalism of the 1960s between the celebration of ethnic and cultural pluralism on the one hand and the applauding of individual autonomy and the rejection of ethnic and religious divisions on the other. In esteeming Fiddler, American Jews were generally oblivious to the fact that they were being asked to simultaneously respect the values of Tevye while accepting the imperatives of the American melting pot. They have remained conflicted, and this tension has remained at the center of the debate over the nature of American Jewish identity.

The Americanized version of Tevye and his daughters has a typically American happy ending. Tevye leaves his village for the golden land and beckons the fiddler to join him, while Chaya and Fyedka are off to Cracow where they supposedly will live happily after. Why a couple from the Ukraine would select a Polish city is left unstated. “What the show ultimately celebrates was this melting pot called America,” its producer, Hal Prince, recounted. “At the end of the show, that’s where they were going.… And that’s the strength of this country — its identification with so many cultures and religions. It’s an amazing experiment that worked.”

Sholem Aleichem, in contrast to the Americans responsible for Fiddler, was not enamored of America. In his story “Tevye Goes to Palestine,” his daughter Bielke marries Padhatzur, a wealthy man embarrassed by his lower-class father-in-law. Padhatzur wants to get Tevye out of the war and says he will pay if Tevye relocates to the United States. “The colossal nerve of this contractor,” Tevye says. “Telling me to give up an honest, respectable livelihood and go off to America.” Padhatzur then suggests Palestine as an alternative destination, and Tevye prefers immigrating to primitive Palestine is better than remaining in his village and being subjected to the insults of his son-in-law.“ But Padhatzur goes bankrupt, is unable to fund Tevye’s relocation, and flees along with Beilke to America one step ahead of his creditors. “America is “where all the unhappy souls go, and that’s where they went.” Padhatzur was not the only one of Sholem Aleichem’s characters forced to move to America. Another is the son-in-law of Ephraim the Matchmaker, a crook and wife-beater. It would appear that for Sholem Aleichem is a refuge of scoundrels, and this might reflect his own troubled life in the United States.

In “Get Thee Out,” the last of the Tevye stories, Tevye is left wondering where he will end up after being forced out of his village. He resembles a cork on an ocean wave, and the possibilities where he might land include Odessa, Warsaw, and even America. In any case, the choice is not his, and he is a passive onlooker. In Fiddler, however, Tevye in an act of affirmation sets off to America with Golde (in the short story “Get Thee Out” Golda is deceased) and three of his daughters.

But what about Palestine? Tevye had looked forward to settling in Palestine courtesy of Padhatzur’s money. “I’ve been drawn for a long time toward the Holy Land,” he says. “I would like to stand by the Wailing Wall, to see the tombs of the Patriarchs, Mother Rachel’s grave, and I would like to look with my own eyes at the river Jordan, at Mt. Sinai and the Red Sea, at the great cities Pithom and Raamses.” Palestine is not a possible destination for Tevye in Fiddler, for Tevye, but it is for Yente, the town’s busybody. She declares she is going to take her “old bones” to Palestine and continue her career in matchmaking. “Children come from marriages, no? So I’m going to the Holy Land to help our people increase and multiply. It’s my mission.”

But what about Palestine? Tevye had looked forward to settling in Palestine courtesy of Padhatzur’s money. “I’ve been drawn for a long time toward the Holy Land,” he says. “I would like to stand by the Wailing Wall, to see the tombs of the Patriarchs, Mother Rachel’s grave, and I would like to look with my own eyes at the river Jordan, at Mt. Sinai and the Red Sea, at the great cities Pithom and Raamses.” Palestine is not a possible destination for Tevye in Fiddler, for Tevye, but it is for Yente, the town’s busybody. She declares she is going to take her “old bones” to Palestine and continue her career in matchmaking. “Children come from marriages, no? So I’m going to the Holy Land to help our people increase and multiply. It’s my mission.”

In the 2004 Broadway revival of Fiddler, Yente is no longer a soldier in the demographic war between Jews and Arabs but a feminist unconcerned with the future of the Jewish state. Joseph Stein, who also wrote the book for the revival, now has her proclaim, “I just want to go where our foremothers (sic!) lived and where they’re all buried. That’s where I want to be buried — if there’s room.” Israel is overcrowded, where old Jews come to be buried, and where the problems between Jews and Arabs have miraculously dissolved. If Palestine for Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye is the Promised Land, for Fiddler’s Tevye America is the land of promise. Here again Fiddler reflects the political sensibilities of its makers.

Edward Shapiro is professor of history emeritus at Seton Hall University and the author of A Time for Healing: American Jewry Since World War II (1992), We Are Many: Reflections on American Jewish History and Identity (2005), and Crown Heights: Blacks, Jews, and the 1991 Brooklyn Riot (2006).

Related Content:

- Reading List: Sholem Aleichem

- The Golden Age Shtetl: A New History of Jewish Life in East Europe by Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern

- Reading List: Jews and the Theater