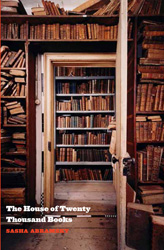

Sasha Abramsky has been blogging here all week on The ProsenPeople’s Visiting Scribe series. Earlier this week, he wrote about the continuity of reading across Jewish generations and observance and the mystical experience of writing a memoir, observed as he worked on The House of Twenty Thousand Books.

Libraries tell stories. The books, the places those books were published, the materials used in their production; the paper trail of previous owners of those books, and the connections from one volume to the next — all are pebbles marking hidden paths.

My grandfather, a historian both of Jewish history and of socialist history, owned a lot of books. By weight — which is of course a useless measure of bibliographic worth, but which at least tells you something about how many pages he plowed through over a lifetime of reading — there were several tons of books in his house when he died in 2010. They resided on double-stacked, floor-to-ceiling shelving in every room of the house except the kitchen and the two bathrooms. I worried, only partially in jest, that the house would collapse when the books were removed from the walls. By geographic locale, there were books originating in cities as far afield as early sixteenth century Constantinople, seventeenth century Amsterdam and Antwerp, eighteenth century Warsaw and Vilna; books from the United Kingdon, the United States, from Russia and Israel and numerous other epicenters of the Jewish and socialist experiences. By topic matter, the books — and by extension the conversations — at the house covered Biblical history, Kabbalah, medieval Europe, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the Age of Revolution, Jewish art, Yiddish political tracts, the origins of capitalism, classical philosophy, the scientific revolution, and a host of other disparate themes.

Chimen collected vast numbers of words: books, manuscripts, letters, dissertations. He had Karl Marx’s membership card of the First International and he owned first-edition copies of Spinoza’s publications; there were letters written by Chaim Weizmann, as well as mathematical treatises penned by Jewish scholars in the early Ottoman period. 5 Hillway may have been the only suburban house in north London with its own Bomberg Bible. It hosted a collection of William Morris materials to rival that held in the British Library.

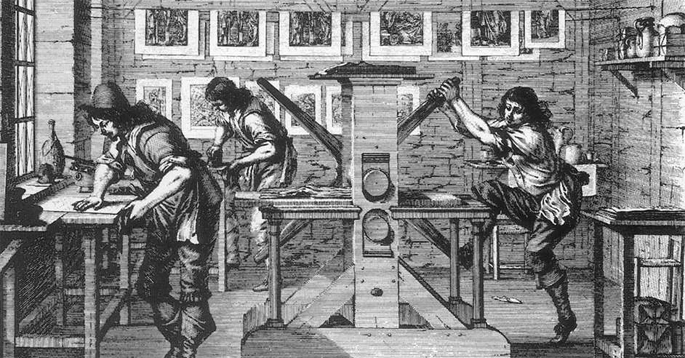

Each document in that cluttered house told a story, albeit oftentimes an incomplete one. Each book had a legion of people behind it: those involved in the writing, the production, the distribution, the purchasing. For Chimen, who knew most every rare books dealer in the Western world, and who spent years doing consulting work as a manuscripts’ specialist for Sotheby’s auction house, each book was a mystery. He knew which editions contained which misprints; which footnotes led up blind alleys; which publishers had suffered censorship at the hands of which political and religious figures. If a printer decamped, say, from Inquisition-era Spain and relocated to Mantua or Antwerp, Holland or Istanbul, that told you about zones of safety, about  which cities at any given moment exuded a tolerant enough culture to generate an active, and critical, book-printing scene. If a printing methodology began in one city and, within a few years, had spread to another, again that told you something about how technology spread, about commerce routes, trade patterns, even immigration pathways.

which cities at any given moment exuded a tolerant enough culture to generate an active, and critical, book-printing scene. If a printing methodology began in one city and, within a few years, had spread to another, again that told you something about how technology spread, about commerce routes, trade patterns, even immigration pathways.

I began working on The House of Twenty Thousand Books as a way to memorialize my grandparents. I finished working on it with a renewed sense of awe at the endless realms of knowledge generated by human culture over the centuries. No single library, no matter how majestic or ambitious, can ever hope to encapsulate more than a fragment of all of this learning. Chimen, who made as good a stab at polymath-status as anyone I have ever met, was all too aware of this. His library was a set of extraordinary fragments, a university unto itself. But even such a library is, ultimately, ephemeral, as fragile a part of history as the events and people and places contained within the texts of its many volumes. As Karl Marx once wrote, “All that is solid melts into air.”

Sasha Abramsky grew up in London and attended Balliol College, Oxford, where he studied politics, philosophy, and economics. He is a Senior Fellow at Demos think tank and teaches writing at University of California Davis. His memoir The House of Twenty Thousand Books is now available from New York Review Books.

Related Content:

- Steve Stern: A Yiddishist in Vilnius

- Matthew Baigell: Social Concern and Left Politics in Jewish American Art

- Liana Finck: A Bintel Brief: A Bundle of Letters

Sasha Abramsky grew up in London and attended Balliol College, Oxford, where he studied politics, philosophy, and economics. Abramsky is a journalist and author whose work has appeared in The Nation, American Prospect, The New Yorker Online, and many other publications. His most recent book, The American Way of Poverty: How the Other Half Still Lives, was listed by The New York Times as among the one hundred notable books of 2013. He is a Senior Fellow at Demos think tank and teaches writing at University of California Davis. Abramsky lives in Sacramento, CA with his wife and their two children.