with Shira Schindel

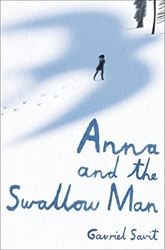

Jewish Book Council sat down with Gavriel Savit to discuss his debut novel, Anna and the Swallow Man, the velvety mind of Borges, Holocaust fatigue, and the beauty of not knowing. Much like the experience of reading his compact and inspiring book, in talking with the author we learned a lot in a short amount of time.

Shira Schindel: I personally loved Anna and the Swallow Man, and can’t wait to pass it on to friends and family. Have you been surprised by adults’ interest in this book, which is billed as being for young readers?

Gavriel Savit: It’s interesting how when you write a story that’s centered around a young woman, it gets received as being on the more juvenile side, and that’s an unfortunate reality of the way we think of women’s narratives in the world right now. But, it also sort of opened up the book. I didn’t immediately think of it as a child’s narrative, but I do think it’s fundamentally a story about a magical time and mindset in childhood, the immediacy of which a lot of us forget as we get older.

Gavriel Savit: It’s interesting how when you write a story that’s centered around a young woman, it gets received as being on the more juvenile side, and that’s an unfortunate reality of the way we think of women’s narratives in the world right now. But, it also sort of opened up the book. I didn’t immediately think of it as a child’s narrative, but I do think it’s fundamentally a story about a magical time and mindset in childhood, the immediacy of which a lot of us forget as we get older.

I also think we are very fortunate right now that what has traditionally been considered generic fiction — speculative, detective, children’s — is falling by the wayside. Young adult narratives are en vogue. There’s no shame in reading a book we enjoy.

SS: What about Holocaust narratives? There are many out there who say we’ve published enough books on the subject matter.

GS: I admit I also have a degree of Holocaust fatigue. There is so much out there that seems to tread the same ground over and over again. A lot of it, for me, devolves into misery porn and I don’t want that.

There is a book I read by Yan Martel, Beatrice and Virgil, that deals with the difficulty of introducing art and story into the space of World War II and Holocaust narratives.  There is so much art created about the Holocaust, and a lot of it seems to be very concerned with portraying horror. Which is obviously real, and I would never want to minimize the horror of that time and place.

There is so much art created about the Holocaust, and a lot of it seems to be very concerned with portraying horror. Which is obviously real, and I would never want to minimize the horror of that time and place.

It seems to me, however, that human beings live full lives even in the most atrocious of situations, and it’s somewhat regrettable that it’s not always possible to see the nuance in human experience within these terrible situations. That, I feel, is one of the most fascinating things: How do you grow up surrounded by this horrible danger?

But maybe the answer is simply: What is the alternative?

SS: In what ways has your Jewish upbringing influenced you as a writer?

GS: My Judaism is narrative, which was true from a very young age. I think that, in very strong ways, those of us who had the privilege of a Jewish education when we were young also received textual ambiguity from that age. At this moment of discovering what story, narrative, and literature is I was simultaneously receiving some of the most complex, multifarious stories in the Western Cannon.

I seem to have trouble not incorporating Jewish characters, or Judaism, into the things I write. I started with the Swallow Man and Anna and everything else grew out of them — Reb Hirschl was a wonderful surprise: he is the kind of person who cultivated thinkers are likely to dismiss off the bat, but he’s a smart guy. I love that he carries that around, and doesn’t need to show it to you outright.

SS: Names, or the forfeiting of one’s given name, play a key role in the book. Does the Swallow Man have a name other than the one you gave him?

GS: The Swallow Man does have a name, and I suspect his name sounds very much like other people’s names. He has not told me precisely what it is, and I’m not going to ask him, because I think that would be a mistake.

SS: It must be very exciting to be a debut author. Is there anything you’re particularly excited about, besides hearing how readers respond to your book?

GS: I’m excited to talk to librarians about the book, and speak about it in schools in general. When I was a kid, I read a lot of the Redwall series by Brian Jacques. I remember discovering that there was this person behind the books, the author. One of the things you’re always taught is that there’s “title by author.” That’s the formula, but I don’t think I really understood what it meant until I was deep in the universe of this guy’s books — there was one dude writing all of this! I finally looked up Brian Jacques on the (then terribly slow) Internet, and there he was. There’s something wonderfully wizardly about discovering that. I’m looking forward to seeing it from the other side.

SS: What do you hope readers will learn from the book that they may not have known before?

GS: For me, the book — insofar as it’s about anything that is reducible to a phrase — is about not knowing, and the ways in which that is magical. I know uncertainty is an uncomfortable state for a lot of people, but if someone can get to the end of the book and understand the tantalizing glory of not quite knowing something I know, I think the book will have been a success.

SS: So you won’t give us any reveals as to what happens next to these characters?

GS: I’m not sure there are any satisfying answers. At the end of the book, you already know the answers, and if I tell you it would take away the answer you already know.

The hardest part of this book to write was the ending. It’s a delicate thing and it’s hard to know what should be articulated and what shouldn’t be. I went through a few drafts of the ending that more explicitly told what happened to Anna later in life, so I have some ideas about what I think she might have done or lived through. But I don’t imagine that living through something like that is likely to dispose you to talk very much about it. I think if there are people who you do talk to about it, they are few in number and very select.

SS: Your editor, Erin Clarke, declares that Anna sits “at the intersection of magic realism and fairy tale.” How have fairy tales influenced your writing?

GS: I love the aesthetic of fairy tales and the way they feel. That’s something I’ve carried into adulthood from childhood. Fairy tales all seem to take place in this amorphous world in which there has recently been a war and people are in danger. It occurred to me that the moving around that is precipitated by that kind of danger and uncertainty also happened in Europe seventy years ago.

In some ways World War II is the perfect backdrop for a new fairy tale. A lot of people feel like telling stories that are related to World War II and the Holocaust in any way other than realism, or journalism, is irresponsible. Obviously, documenting and remembering is important across the board, but that’s not exclusive of art. What is horrific about the Holocaust is not that there were unthinking human beings, but rather that real people who thought, and felt, and worried, committed atrocities. I hope that the book is successful in exploring that territory, and that it doesn’t upset people who are more committed to the factual history. That said, my philosophy is that if any story is worth telling, it’s probably going to upset somebody.

SS: Are there any books or writers that particularly inspired you in writing your novel?

GS: My magical realism patron saint is Jorge Luis Borges. I love his brain. It’s so much fun and so enchanting. It’s got this wonderful, dark red velvet texture that I like to wrap around myself. It’s fantastic.

Obviously also Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief; people would be insane not to read it.

Most of my influence has come from diverse directions. I’m attracted to historically and culturally relevant magical realism. It’s a bizarre suggestion, but Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke imagines what it would be like if magic existed at the turn of the nineteenth century in England. It’s a great book and feels to me like the sort of thing that exists in the world and implicates things that don’t exist in the world.

SS: The following passage from your book particularly stood out to me; what did this moment in the book mean to you?

“What makes it special?” said the Swallow Man. “It’s a bird. A bird that flies and sings. And if the wolves and bears have their way, no one will ever fly or sing in precisely the same way that it does. Never again. Does it need to be more special than that?”

GS: That particular section is something that I continue to think about. It’s really kind of a morally and emotionally complex thing that human beings have this deeply conservative tendency. We like things to be the way that they were before. It’s interesting to look at it in the context of endangered species. On a fundamental level — and I do not advocate anything destructive in our natural environment — evolution works: entities compete, the more successful continue to survive, the less successful fall by the wayside and when the environment cannot continue to bear a flourishing or more successful entity eventually they begin to die off. That’s the sort of fail-safe of evolution and environmental activity. But we as human beings have this beautifully and terribly irrational nostalgia for things that we have seen before. So we have certainly created an aberrant natural environment where a lot of creatures that were around when we were less powerful cannot exist. It’s a shame, but that’s the way it is. We still have this strongly irrational urge to keep them around, even if they are naturally unsuited to continue to exist.

I think rational thought and reasoning are a tremendously useful tool. But that urge humans have to keep the beautiful bird, the one that flies like no other, speaks very highly of human irrationality. I’m afraid of a world that contains a fundamental imbalance between human rationality and irrationality, in either direction. I’d like to see the most rational people embrace a measure of irrationality, and vice versa.

In the meantime, I’ll probably just watch the birds fly around.

In the meantime, I’ll probably just watch the birds fly around.

SS: You write in the book that “A question holds all the potential of the living universe within it.”Are there any questions you’d like to leave us with now?

GS: Yes.

SS: Is that it?

GS: Yes.

Shira Schindel is the Director of Business Development & Author Engagement at Litographs and formerly the head of Content and Acquisitions at Qlovi, an education technology startup accelerating literacy in K‑12 classrooms. Before that she worked in the literary department at ICM Partners, and studied Creative Writing at Columbia University.

Related Content:

- Emerging Voices: Interviews with Up-and-Coming Authors of Jewish Literature

- James Patrick Kelly and John Kessel: Defining Kafkaesque

- Holocaust Books for Young Adults