with Bob Goldfarb

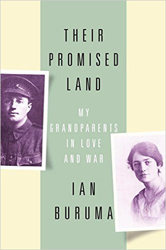

InTheir Promised Land, Ian Buruma tells the extraordinary story of his own grandparents: British Jews who were apart during the World Wars and stayed in touch by writing letters across the distances that separated them. His book is part history, part memoir, part love story.

Bob Goldfarb: When did your grandparents’ letters first come into your hands?

Ian Buruma: The first time I read some of them was in 1999, when I was working on Anglomania,a book about European Anglophilia in the United States. I knew where the letters were — in a family archive, in a barn, in a country house that belonged to one of my uncles. I thought for a long time that it would make a book of some kind. But it was only a year or two ago that I brought them to America.

BG: What prompted you to make this a book?

BG: What prompted you to make this a book?

IB: I thought the material was very rich and told a story, not just about them but also about the history of the twentieth century. A novel came to mind, but I felt that would be a waste of the material, because the letters themselves are so interesting. Simply editing my grandparents’ correspondence was also not quite the way, either. So I had to feel my way towards a form, and the idea came to me around the early 2000s.

BG: You seem to have a particular interest in the world as it was just before you came into it.

IB: When you think of families of people my age, there are families where the parents had experiences of World War II. In some families it was never spoken about, partly because it was too painful for the parents, or because they children weren’t interested. For me that was never the case; I was always interested. Adults in my family would talk, from when I was a boy. So, yes, I was always interested in that. I don’t know why. Perhaps it’s because it was so frightening that a world that seemed so settled, like Europe after World War I, could suddenly erupt in a kind of nightmarish hell.

BG: Your grandparents seem to have been aggressively assimilated into the larger culture in which they lived. Can we draw conclusions today from the lives they lived then?

IB: They came from a tradition that had been assimilationist since at least the eighteenth century. So their grandparents would no longer have lived in the Judengasse in Frankfurt where the family lived originally. They had been very German already, one of those families that had a history of living in Germany longer than most so-called “native” Germans. My grandparents were following in that tradition even though they were British rather than German.

As you know, a lot of this has to do with class. The more people move up and become prosperous, the more they let go of the culture of the old country. They are very much a manifestation of that — not just them, but also their parents. To me one of the most interesting passages from Their Promised Land is the exchange between my great-uncle and Franz Rosenzweig. Rosenzweig was so impressed by the Polish Jews he met during World War I — he felt they were more at ease in their skin because they had a clearer sense of who they were.

BG: Your grandparents defined themselves largely in terms of culture, especially classical music. What was there about classical music in particular?

IB: So many German Jews loved Wagner. To worship at the shrine of Bayreuth was to take part in a kind of mystical sense of being German without having to be Christian.

The other thing is, it’s easy to see why German culture dovetailed with a certain Jewish experience. The Germans didn’t have a state of their own until very late, and they had to distinguish themselves from the rationalism of France and French philosophy. The reason that music can play such a powerful role is that it’s abstract, so you can feel you’re taking part in a high culture almost in a religious way, without converting to a faith. My grandparents were part of that tradition, where classical music defined you as a person of high culture.

BG: Did you ever feel you were intruding when you were reading their letters?

IB: Yes, of course. I would never have dreamed of doing this if they’d still been alive. But I do feel that once people are gone, and their experience — even their intimate lives — are of historical interest, then it’s legitimate to let it be known. I made very sure that my aunt, the last surviving member of my mother’s generation, read it, so that I wouldn’t do it behind their backs. My main concern was not so much what they would have thought, because they are no longer there, but rather to make sure I didn’t hurt those who are still alive.

It’s very interesting when you are writing about family, people who are close to you. It’s always very difficult, because others who felt equally close to them will have a slightly different picture. It’s very rare that you can do something like this and please one’s siblings, or people who were also close, because it’s not necessarily the image they have. The greatest skepticism has come from people who knew them — from my sister, and my father, and so on.

BG: You’re not afraid at some points to talk about events that were personal, even personally embarrassing episodes about yourself.

IB: I don’t think they were embarrassing because it was a long time ago. Once something becomes a story, it’s not like a confession — and I’m not by nature a confessional person. I’ve just finished reading a memoir written by Stephen Spender’s son about his parents, and he goes into the sex lives of his parents, and his own. I could never do that. I could never imagine wanting to do that.

IB: I don’t think they were embarrassing because it was a long time ago. Once something becomes a story, it’s not like a confession — and I’m not by nature a confessional person. I’ve just finished reading a memoir written by Stephen Spender’s son about his parents, and he goes into the sex lives of his parents, and his own. I could never do that. I could never imagine wanting to do that.

BG: Do you find writing a story like this very different from writing fiction?

IB: Yes, because you don’t have to make anything up! The structure here is still slightly novelistic; it is a way of telling a story. But I do find it easier applying a certain novelistic technique to something that is factually true than to making up a story.

Bob Goldfarb is Director of Institutional Affairs at the Forward. He lives in New York.

Related Content:

- Sarah Wildman: Paperless Love: An Unsettling Departure

- If a Place Can Make You Cry by Daniel Gordis

- Miranda Richmond Mouillot: How to Ask?

Bob Goldfarb is President Emeritus of Jewish Creativity International.