Books Discussed in This Essay

- The Best Place on Earth: Stories by Ayelet Tsabari

- Talking to the Enemy by Avner Mandelman

- The People of Forever Are Not Afraid by Shani Boianjiu

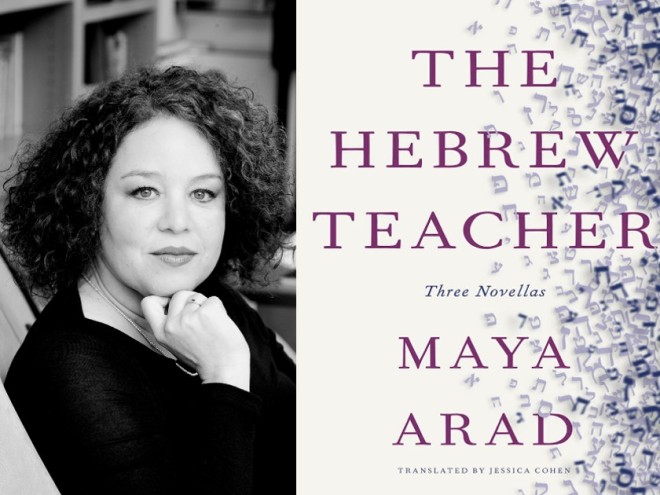

Literary critics have lately feted what some are calling a “new” Israeli literary diaspora constituting expatriates who continue to write in Hebrew even after living abroad for many years (they include Dorit Abusch, Maya Arad, Ari Lieberman, Ruby Namdar, and, most recently, renowned Palestinian-Israeli novelist Sayed Kashua). Indeed, the University of Cambridge is devoting an entire conference to this “trend.” Yet while the truth is that there has actually been a dedicated subculture of Hebrew writing in North America since at least the 1920s, an arguably more intriguing movement of writing has emerged, created by Israeli expats or others who have gained singular perspectives on their troubled society from their prolonged sojourns abroad and are determined to reach out directly to English readers. If the three books discussed here are any indication, their voices may constitute some of the boldest and most exciting writing reflecting Israel’s troubled reality today. And as it happens, each has been the recipient of prestigious literary awards.

Ayelet Tsabari draws on many personal and familial layers in her first collection, not surprising for one who grew up among six siblings in a struggling Yemenite household in Petah Tikva. Reflecting on her identity after two decades living in Canada, Tsabari suggests that the seeds for her current identity as an expat writer were mysteriously planted within her long ago: “For some strange reason, I’ve always felt in the margins, and felt comfortable in the margins. I’m an exile by choice, but where did it come from, when did it start?” That sensibility certainly resonates in her sharp portrayal of memorable characters such as the prickly matriarch of “Invisible”; frequently reminiscing about her final days in Yemen, she feels only a tenuous sense of belonging to her ostensible homeland, Israel.

In considering this and other characters’ alienations, one cannot help but think of how the collection’s evocative title (The Best Place On Earth) reflects Tsabari’s personal sense of displacement: “This sense of not belonging early in life…I wonder if it’s losing a parent at an early age, a sense of looking for him in the world, looking for a place that would be that type of connection.” Her eleven stories, each a vivid immersion in a different Israeli topos (Haifa, Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, Eilat, Negev), are distinguished by a resolute open-endedness, a quality that ensures her characters and their possible futures will linger with us just a little longer. It is rare to encounter any short-story collection (let alone a first book) without some unevenness, yet remarkably that is not the case in this exceptional collection. The Best Place On Earth is positively brimming with exilic protagonists (each a transient, nomad, or displaced in one way or another) who find themselves challenged by myriad forms of boundaries and contact zones.

In spite of the book’s uniform excellence, it seems worth singling out a few that boldly brush against the grain of some of the well-worn conventions of alienation often associated with Ashkenazi Israeli writers. For instance, in “Below Sea Level,” the anticipated clash between a traditional Zionist father and a diffident son takes an unexpectedly redemptive turn, while in “Borders” (a title that could well serve the entire volume) the young protagonist vacationing in Eilat on the cusp of her army service comes to a startling revelation about a very different patrimony. And while this entire collection refreshingly presents Israeli reality from the perspective of Mizrahi characters, nowhere is that more moving than in “The Poets in the Kitchen Window” where young Uri’s sense of self and possibility seems irrevocably transformed when he first encounters the forceful lyricism of Iraqi-born Israeli poet Roni Someck. Tsabari’s gifts for open-ended destinies, sharply revealing conversations that establish character, and the transformative potential of quotidian encounters, is often suggestive of how Grace Paley, an acknowledged master of the American short story, might have sounded had she delved into the lives of younger native-Israeli heroines rather than working-class New York wives and mothers. So just where is “the best place on earth”? Perhaps wherever one manages to live wholly and authentically, these stories seem to suggest. Tsabari is currently writing her memoir as part of a three-book contract with Random House.

It is difficult to describe the experience of encountering the visceral stories in Avner Mandelman’s gritty and violent Talking to the Enemy for the first time, but every year, I see their impact on the startled faces of my students who often single his work out as their favorite writing of the semester. Born in Israel in the fateful year of 1947, Mandelman’s entire oeuvre seems dedicated to tough moral examinations of the repercussions of the rebirth of Jewish sovereignty, especially in the lives of those caught up in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The news one finds in his raw portrayals of those dedicated to defending Israel is often very bleak, informed by the writer’s own life. From 1965 to 1968, Mandelman served in the Israeli Air Force and fought in the Six Day War; later he emigrated to Canada where his literary expression found a welcome home. His works were selected for both The Best American Short Stories and the esteemed Pushcart Prize anthology. Talking to the Enemy won the Sophie Brody Award for Jewish literature and a subsequent collection, The Cuckoo, and his suspenseful novel The Debba (inspired by the distress he felt in the early traumatic days of the Yom Kippur War) each received strong acclaim.

It is difficult to describe the experience of encountering the visceral stories in Avner Mandelman’s gritty and violent Talking to the Enemy for the first time, but every year, I see their impact on the startled faces of my students who often single his work out as their favorite writing of the semester. Born in Israel in the fateful year of 1947, Mandelman’s entire oeuvre seems dedicated to tough moral examinations of the repercussions of the rebirth of Jewish sovereignty, especially in the lives of those caught up in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The news one finds in his raw portrayals of those dedicated to defending Israel is often very bleak, informed by the writer’s own life. From 1965 to 1968, Mandelman served in the Israeli Air Force and fought in the Six Day War; later he emigrated to Canada where his literary expression found a welcome home. His works were selected for both The Best American Short Stories and the esteemed Pushcart Prize anthology. Talking to the Enemy won the Sophie Brody Award for Jewish literature and a subsequent collection, The Cuckoo, and his suspenseful novel The Debba (inspired by the distress he felt in the early traumatic days of the Yom Kippur War) each received strong acclaim.

These shocking, plot-driven stories plunge readers deep into both the inner and outer geographies of contemporary Israeli reality. Mandelman’s shattering language reliably entertains, quickening our pulse like an airport novel, but also demands our attention to the troubling moral quandaries presented by the shifting position of the powerful and the powerless. This occurs most prominently in the disturbing fable “Og” in which a golem-like figure is perpetually resurrected to confront a mythical kingdom’s enemies but at a great cost. It unfolds with the logic of a nightmare and serves as a powerfully timeless coda to the preceding stories set in the gritty present. Perhaps the most memorable stories concern the recurring character, Mickey, a Mossad agent and son of Holocaust survivors, who narrates episodes that span a lifetime, beginning in “Terror,” where his betrayal of his younger brother earns a violent lesson from his father, the stark doctrine that will rule over the rest of his life: “Is it good for my people?” The sacrifices made by a generation inheriting the unresolved conflict left by the previous is never more palpable than in Mickey’s bleak observation that “I had been under Operational Rules ever since I had joined, nineteen years before, just as my father had been, ever since he had arrived in Palestine, more than 50 years ago.” Cumulatively, the stories of Talking grapple brilliantly with that unsparing legacy: the nature of being hard and the costs of that condition.

In interviews Mandelman has remarked on his preoccupation with the problem of “how much necessary evil can be allowed by a civilized society,” and I can’t think of a writer who provides better insight into that question and indeed the entire Israeli psyche, in which the unbearable tensions of life in a society so devoted to the triumph of strength and toughness that life itself can seem a fortress. Whether exploring a Mossad operation gone badly astray, childhood trauma, or familial strife, the ancient biblical palimpsest is always an insistent presence, lurking just beneath reality, beneath language itself. Mandelman’s acerbic attunement to the tragic ways in which ancient scripts of violence are encoded in the conflicts of his homeland is succinctly captured in a rueful salutation from the penultimate page of Talking: “I would like to acknowledge the ancient fictioneers who anonymously wrote the all-time bestseller, and who, astonishingly, managed to convince half of humanity that it is entirely normal to live one’s life according to antique fictions. Without this marvelously original con job, I would have little to write about.” All the heartbreak, hilarity, and horror in Talking seem to derive from this epiphany.

Like Mandelman, Shani Boianjiu uses language that is shrewdly illustrative of the undeniably corrosive effects of military culture on young Israelis, especially the toll taken on female soldiers. Her complex and tough-minded The People of Forever Are Not Afraid was shortlisted for the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature and excerpted in The New Yorker—a substantial achievement for such a young, first-time novelist. Moreover, she is the youngest recipient ever of the U.S. National Book Foundation’s 5 under 35 Award. Boianjiu grew up in Kfar Vradim, one of Israel’s so-called “peripheral” communities, a small village in the Galilee close enough to the Lebanese border that it was embattled by frequent Hezbollah rocket attacks. Though Boianjiu first began to write during her IDF service, those early efforts were entirely discarded and her first book originated in a creative writing class undertaken while studying English at Harvard University.

For anyone still accustomed to thinking of the war story as a masculine genre, this brave first novel may be a revelation. Boianjiu first began to write during her IDF service and the fact that she chose to write in English results in an undercurrent of destabilization that produces the notes of surrealism familiar to anyone who has ever served in the military of any country. As she told the New York Times, that choice “forced me to think carefully about every word I used.” Perhaps because of that mindfulness, the young voices of Boianjiu’s protagonists are both brash and vulnerable, often at the same time. We first meet Yael, Avishag, and Lea, just as they are about to graduate from a small high school in a remote development town. In the novel’s savvy bookending structure, we meet them again as civilians after their IDF service where we confront the implications of how nothing and yet everything has changed for them.

In addition to her nuanced portrayals of her three protagonists, Boianjiu evinces profound concern for the fate and identity of “the other” and her empathic portraits in The People of Forever’s loosely-structured plot (best to think of this work as stories linked by recurring characters rather than a conventional novel) take us deep into how the myriad unsettling realities of the Middle East affect individual lives. For instance, in “Checkpoint,” Lea can’t help obsessing over the marriage and domestic life of Fadi, a Palestinian man she encounters as he crosses into Israel from the West Bank in search of day labor. Elsewhere Boianjiu deftly maneuvers between the alternating perspectives of Avishag and a desperate Sudanese refugee who hurls herself onto the barbed-wire fence at the Egyptian border. In The People of Forever’s uneasy, and occasionally caustically humorous episodes, Boainjiu renders unforgettable portraits of characters trapped between girlhood and womanhood, not only beleaguered by questionable security missions that severely challenge their sense of values and selfhood but damaged by sexual harassment, and worse, from their fellow soldiers. Though her first book was written while living in the United States and Ireland, she is now back in the Western Galilee at work on her second novel.

Any reader wishing to understand Israeli reality, both its claustrophobic togetherness and its fragmentation, and the heavy burden borne by its young citizen-soldiers will find each of these powerful books deeply rewarding. As should be evident by now, in addition to their expatriate sensibilities, the works of Tsabari, Boianjiu, and Mandelman also share a profound concern for the fate of Israel’s myriad “Others”, whether the alienated Arab minority, the ambivalences of Mizrahi Jews, or the homesickness of Philippine caregivers. And something else: each of their singular insider-outsider perspectives bears witness to the inevitable coarsening of young people (and by extension, their entire society), wrought by their military service and a conflict with no end in sight. Finally, while the choice to write in the English language may still be a relatively minor phenomenon, it seems worth noting that the acclaimed Israeli artists Rutu Modan (Exit Wounds and The Property) and Yirmi Pinkus (a founder of the graphic novel publishing house Actus Tragedus) have both been publishing their graphic narratives in English since the early 2000s.

Any reader wishing to understand Israeli reality, both its claustrophobic togetherness and its fragmentation, and the heavy burden borne by its young citizen-soldiers will find each of these powerful books deeply rewarding. As should be evident by now, in addition to their expatriate sensibilities, the works of Tsabari, Boianjiu, and Mandelman also share a profound concern for the fate of Israel’s myriad “Others”, whether the alienated Arab minority, the ambivalences of Mizrahi Jews, or the homesickness of Philippine caregivers. And something else: each of their singular insider-outsider perspectives bears witness to the inevitable coarsening of young people (and by extension, their entire society), wrought by their military service and a conflict with no end in sight. Finally, while the choice to write in the English language may still be a relatively minor phenomenon, it seems worth noting that the acclaimed Israeli artists Rutu Modan (Exit Wounds and The Property) and Yirmi Pinkus (a founder of the graphic novel publishing house Actus Tragedus) have both been publishing their graphic narratives in English since the early 2000s.

In Jews and Words, a charmingly iconoclastic account of Jewish languages and literatures, coauthors Amos Oz and daughter Fania Oz-Salzberger celebrate the fact that “Jews around the world have not been so mutually intelligible since the fall of Judea” due to the increasing conversation of Hebrew and English, “the two major surviving languages of the Jews…[both are very much alive in this role. There is still something of a chasm between them but many bridges are being built; the present book, written in English by two native Hebrew speakers, is one such bridging attempt.” Moreover, even the much-celebrated writer Etgar Keret has elected to publish his much-anticipated memoir The Seven Good Years exclusively in English. An examination of an unusual family that reads like a microcosm of Israel itself (a child born on the day of a suicide-bombing; an ultra-Orthodox sister who has eleven children; a dovish, marijuana-smoking brother; and Holocaust-survivor parents), promises to expand the horizons of Israeli literature. While not strictly in the category of expat literature, this growing trend may represent something even more interesting. Perhaps, as the marginalization of Israel grows, its writers are growing more restless, eager to escape the insularity of their traditional audience and plunge directly into the uncertain reception of a much wider readership.

Ranen Omer-Sherman is the JHFE Endowed Chair in Judaic Studies at the University of Louisville and his latest book is Imagining the Kibbutz: Visions of Utopia in Literature & Film.

Related Content:

- Writing in a Foreign Language by Shani Boianjiu

- Reading List: Contemporary Israeli Literature

- Reading List: Israel Classics

Ranen Omer-Sherman is the JHFE Endowed Chair in Judaic Studies at the University of Louisville, author of several books and editor of Amos Oz: The Legacy of a Writer in Israel and Beyond.