Earlier this week, Sabra Waldfogel wrote about Raphael Moses, one of the most eminent Jews in Georgia in the nineteenth century, and Clara Solomon, a Jewish girl who lived in mid-nineteenth century New Orleans. She has recently published Slave and Sister, a novel about Jews and slavery in antebellum Georgia, and has been blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council.

Between 1828 and 1838, Lydia Weston and Isaac Cardozo of Charleston had six children together. They were like husband and wife, and like a family. But they were not. Isaac Cardozo was a Sephardic Jew. Lydia Weston was a former slave.

Between 1828 and 1838, Lydia Weston and Isaac Cardozo of Charleston had six children together. They were like husband and wife, and like a family. But they were not. Isaac Cardozo was a Sephardic Jew. Lydia Weston was a former slave.

A white man of Charleston might love a black woman and their children all his life; he might install her as his “housekeeper”; he might even — scandalously so! — let her preside over his table and his guests. But he could never marry her. Isaac remained a bachelor all his life, staying at home with his long-lived parents. He would never bring Lydia or their children to the Cardozo Sabbath table.

Lydia Weston was connected with two of Charleston’s most eminent families — the Westons, white and black. Lydia’s master, Plowden Weston, was one of the richest planters in South Carolina. When Lydia was twenty-one, Weston granted her freedom. Many freed slaves were the children of their masters, but Lydia was not. Weston owned her a debt of gratitude for nursing him when he was ill. She took his surname, which acknowledged her connection with the white Weston family.

Plowden Weston had children by at least two slave women. One of them, called Toney, was freed at the same time as Lydia. The black Westons became substantial members of Charleston’s community of free persons of color. They were proud of their lineage, prosperous through business or skilled trade, and brown of skin. They held themselves apart from their black and enslaved brethren.

As a Weston, and as the companion of Isaac Cardozo, Lydia Weston was established as a free woman. In the 1840s, she paid the capitation tax levied on free blacks. In 1852, she bought property — she owned her own house. And most astonishingly, she owned slaves. In 1830, there was a girl under ten in her household who was enslaved, and in 1840, a woman over fifty-five.

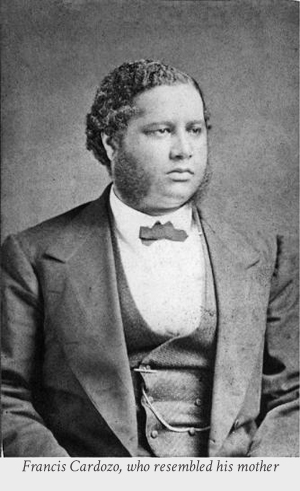

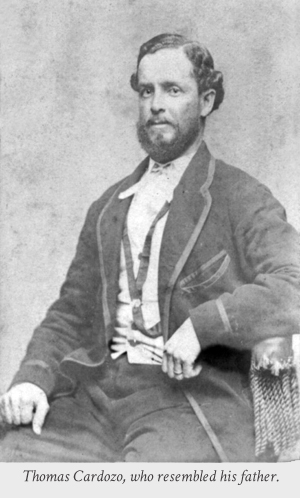

Lydia Weston’s children would never be considered Jews, but they reaped the advantages of being free persons of color. All of them — her daughters Lydia and Eslanda, her sons Henry, Jacob, Francis, and Thomas — were prepared for life with education and a trade. Eslanda and Francis attended a local school for free blacks; Francis was prepared enough to attend the University of Glasgow after he left Charleston. Henry, the eldest son, was erudite enough to join the Clionian Debating Society, a group dedicated to education and intellectual improvement for the brown men of Charleston. The youngest son, Thomas, was also well-educated; he began his career as a teacher.

All of them learned a trade, too. Both of Lydia’s daughters were trained as seamstresses and Henry learned tailoring. Francis was apprenticed to a carpenter.

All of them learned a trade, too. Both of Lydia’s daughters were trained as seamstresses and Henry learned tailoring. Francis was apprenticed to a carpenter.

Did Isaac Cardozo pay his children’s school fees? Did the black Westons, tailors and millwrights, teach Lydia’s children a trade?

As the 1850s dawned, the fate of Lydia and her children changed. The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 put every black person in the United States, free or not, at risk, and the secession fervor of the 1850s, so strong in South Carolina, had free people of color justifiably worried about re-enslavement. After Isaac Cardozo died in 1855, Lydia and her children left Charleston. Francis went to Scotland to study, Thomas to New York to teach, and the rest of the family moved to Cincinnati to make a living.

During Reconstruction, two of Isaac’s sons rose to prominence. Francis served as South Carolina’s Secretary of State between 1868 and 1872, the first black person to hold public office in the state. Thomas was Mississippi’s State Superintendent of Education between 1873 and 1876.

They are known to history by the name of the father who could never claim them as his sons. They are Cardozos.

Sources on Charleston’s antebellum free black community:

No Chariot Let Down: Charleston’s Free People of Color on the Eve of the Civil War, edited by Michael Johnson and James L. Roark (W. W. Norton & Co, 1986), and Marina Wikramanayake’s A World in Shadow: the Free Black in Antebellum South Carolina (University of South Carolina Press, 1989).

Sabra Waldfogel grew up in Minneapolis and received her Ph.D. in American History from the University of Minnesota. Her short fiction has appeared in Sixfold Literary Magazine. Read more about her and her work at www.sabrawaldfogel.com.

Related Content:

- Reading List: Civil War

- Reading List: American Southern Experiences

- Sarah’s Key, Mary’s Secrets, and Truth That’s Stranger Than Fiction by Lois Leveen