Lesbian-feminist poet and scholar Julie R. Enszer has been blogging for The ProsenPeople this week on poetry, loss, and the pioneers of American Jewish lesbian writing. In today’s post, she determines the authors responsible for the second half of “the lesbian-feminist midrash.”

Earlier, I wrote about how much Evelyn Torton Beck’s anthology Nice Jewish Girls means to me as a poet. My new poetry collection, Sisterhood, is in conversation with Nice Jewish Girls, but that isn’t the only book that’s part of the dialogue. Two books from the middle of the twentieth century are also a part of this conversation. Gertrude Stein’s The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas and Jo Sinclair’s Wasteland are both important parts of my imagined Jewish, lesbian, feminist world.

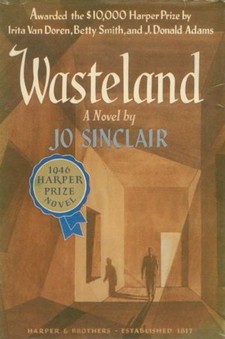

Jo Sinclair’s Wasteland is one of the great, under-recognized novels of the twentieth century. Sinclair is better known for her novel The Changelings, published in 1955, but Wasteland, which won the 1946 Harper Prize with a $10,000 award, tells the story of Jake Brown (Jacob Braunowitz) and his struggle for acceptance in the depression-era United States. Narrated by Jake and his therapist through a series of psychotherapy sessions, Wasteland also provides an early portrait of a lesbian, one who is comfortable with her lesbianism: Jake’s sister Debby.

Jo Sinclair’s Wasteland is one of the great, under-recognized novels of the twentieth century. Sinclair is better known for her novel The Changelings, published in 1955, but Wasteland, which won the 1946 Harper Prize with a $10,000 award, tells the story of Jake Brown (Jacob Braunowitz) and his struggle for acceptance in the depression-era United States. Narrated by Jake and his therapist through a series of psychotherapy sessions, Wasteland also provides an early portrait of a lesbian, one who is comfortable with her lesbianism: Jake’s sister Debby.

Debby encourages Jake to enter therapy to address his own self-hatred. Jake loves his sister, but he does not particularly like that she is a lesbian; then again, Jake doesn’t particularly like many things about his life, including that he is Jewish and that his family is poor. Although we never hear Debby’s voice directly (she is a shadowy secondary figure), in my mind she looms large. She works as a writer for the WPA to help support her family. Debby is a young woman who is lesbian, Jewish, and poor, three conditions that stigmatize her. In spite of this, Debby seems to embody a joie de vivre that inspires even the dour Jake. Debby represents possibility: the possibility of a new life through hard work, the possibility of being a lesbian. While writing Sisterhood, I thought about relationships between siblings, particularly relations that are vexed. Non-saccharin portrayals of siblings interested me most; I like stories about siblings that are challenged, complex, messy, difficult, imperfect. So does Sinclair. Our work expresses this sisterhood.

I first learned about Wasteland while reading letters of lesbian-feminists from the 1970s and 1980s in the archives at Duke University. A few decades earlier, Jewish lesbian-feminists found Sinclair’s Wasteland as captivating as I later did. Through Jake, Sinclair provides us an image of ourselves in an earlier era, an image that is both meaningful and nurturing.

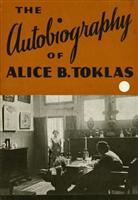

Tracing back my personal literary history of Jewish lesbians, the stop after Sinclair’s Wasteland is Gertrude Stein’s The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933). Stein’s Autobiography made her a popular icon in the U.S. I love the idea of Gertrude and Alice, two nice Jewish ladies, traveling around the country promoting The Autobiography and lifting belly in hotel rooms in the heartland.

Unlike Sinclair’s Wasteland, where we never read directly the voice of Debby, Stein’s Autobiography speaks openly in a lesbian voice, even if through an elaborate conceit in which Stein as the author writes as if she were her lover, Toklas. This dramatic linguistic contortion gives us an explicit lesbian voice, but it is still a voice seen through a mirror with the wink of an eye. Nonetheless, the physical and intellectual intimacy of the two women is present on every page.

Unlike Sinclair’s Wasteland, where we never read directly the voice of Debby, Stein’s Autobiography speaks openly in a lesbian voice, even if through an elaborate conceit in which Stein as the author writes as if she were her lover, Toklas. This dramatic linguistic contortion gives us an explicit lesbian voice, but it is still a voice seen through a mirror with the wink of an eye. Nonetheless, the physical and intellectual intimacy of the two women is present on every page.

Together, these novels open the possibility of being lesbian in the middle of the twentieth century, in a time not our own. They remind me that lesbians are not new or contemporary creations, but they also remind me that speaking in our own voice was not always possible. Sometimes our voices needed to be mediated through brothers or through an elaborate ruse to deflect or re-frame the truth.

In the 1970s, women’s liberation and gay liberation brought to lesbians the possibility of speaking in our own voice; they gave us the ability to occupy the center of the frame. The excitement of the personal and immediate “I,” the assertion of this subjectivity, by lesbian-feminists was crucial to my writing. My work, including my new book Sisterhood, embraces the subjectivity of lesbian-feminists from the 1970s, but when I think back to the mothers of my work, Sinclair and Stein are among them. The struggle to write, to express lives that have been denied and denigrated, is an important part of our literary history. I honor and engage the work of Sinclair and Stein as part of my lesbian-feminist midrash.

Julie R. Enszer is the author of four poetry collections, including Avowed, and the editor of OutWrite: The Speeches that Shaped LGBTQ Literary Culture, Fire-Rimmed Eden: Selected Poems by Lynn Lonidier, The Complete Works of Pat Parker, and Sister Love: The Letters of Audre Lorde and Pat Parker 1974 – 1989. Enszer edits and publishes Sinister Wisdom, a multicultural lesbian literary and art journal. You can read more of her work at www.JulieREnszer.com.