Main gate of Auschwitz, 2011

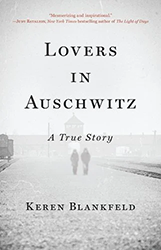

I confess: when I first began researching my new book, Lovers in Auschwitz, I understood little about Auschwitz. A couple of decades ago, I watched Schindler’s List, which gave me a rough idea of life in a concentration camp. Years later, I went to Poland and visited the main camp of Auschwitz. I saw the infamous steel gate with the Gothic-lettered sign: Arbeit Macht Frei–work will set you free. I saw the latrines, the piles of pilfered shoes, the ovens. And still, I didn’t really see.

I am the grandchild of four Holocaust survivors. I cannot remember a time when I didn’t know my grandparents’ stories of survival; their battles and strength are ingrained in me, part of my DNA. Sometimes I feel that I know their past so intimately that I can visualize my grandparents, as children, in Europe. Growing up, I would ask questions and as they remembered, I listened, and I imagined.

A teenage boy, peeking through the cracked door of the closet where his mother hid him. The boy watching, as a Nazi pulled his younger sister up by her hair, shot her square on the forehead, and dropped her – like a rag doll – to the ground.

A girl, age nine, boarding a ship full of orphans setting sail for Tehran, waving goodbye to her grandparents, who would later be gunned down along with the other local Jews, their bodies tossed in the town river.

A young soldier, returning from the front to discover a lone, silent piano in an empty apartment, his entire family dead.

A girl, age twelve, crouched inside a cellar for 630 days, speaking in whispers, making a game of catching gnats.

My grandparents lost most of their families to the Holocaust. Family members who weren’t killed in front of them simply disappeared. But none of my grandparents were in a concentration camp. When I asked them what they knew about the camps, they shuddered. They were lucky, they said in a lowered tone, eyes averted. They had one or two close friends with numbers tattooed on their forearms; perhaps they suspected that their own grandparents had perished in those camps. But my grandparents didn’t talk about the horrors of the camps — and so I averted my eyes, too.

And then, while researching World War II refugees as part of my professional life as a journalist, I met David Wisnia. At ninety-two, David, a cantor with a deep tenor, had the hint of a single-digit six still imprinted in his forearm. At fifteen, he’d discovered his family dead in a pile of bodies in the Warsaw Ghetto; by sixteen, he’d landed in Auschwitz. When I first met David, he briefly told me about his experiences in the camp, first carrying corpses, and later singing to the Nazis. He told me about escaping a death march and joining the US military.

Before I left our meeting, he casually mentioned–I had a girlfriend in Auschwitz. He told me her name was Helen Spitzer, but she was known as Zippi.

I knew enough about Auschwitz to understand that this did not sound right. When David told me about Zippi’s being a graphic designer in Auschwitz, I was astonished. I had much to learn. I read David’s memoir, One Voice, Two Lives: From Auschwitz Prisoner to 101st Airborne Trooper. All of a sudden, those latrines I’d seen so long ago, that steel gate, those piles of shoes – they all began to take new meaning.

Zippi remained an enigma. I couldn’t wrap my head around the idea of a graphic designer within a killing camp. I picked up a copy of Approaching an Auschwitz Survivor: Holocaust Testimony and Its Transformations edited by Jürgen Matthäus. The slim volume captured Zippi’s voice through interviews with five historians, each chapter with its own focus and particular lens. I realized that not only were Zippi and her role exceptional, but so much of what occurred in Auschwitz and its subcamp Birkenau (where David and Zippi were both interned) lay beneath the surface of what is commonly known. Acts of resistance took place in factories, offices, warehouses, and literally underground. A modern onlooker could not begin to understand that world by just looking through the steel gates.

I went on to read many memoirs of survivors of Auschwitz and I emerged astonished every time. Susan Cernyak-Spatz, Zippi’s friend and fellow inmate, wrote Protective Custody Prisoner 34042. Born in Vienna, Susan survived two years in Auschwitz and went on to teach German literature at UNC-Charlotte. Susan described Zippi’s Zeichenstube, or drafting office, where Zippi would organize camp statistics and employ sick girls to allow them to stay inside and be safe until they recovered.

Magda Hellinger spent some time in this office with Zippi. In her memoir, The Nazis Knew My Name: A Remarkable Story of Survival and Courage in Auschwitz-Birkenau, authored with her daughter Maya Lee, Magda described Zippi filling in ledgers with prisoners’ details. The bulk of the list was prisoners who were selected for death. “The worst part of this job was that these registers were sometimes filled out in advance of a selection, meaning Zippy [sic.] was making up causes of death for people who had not yet died,” wrote Magda. Secretly, Zippi switched many of these names to different columns in her ledger, saving countless lives even as she risked her own.

Magda also spent some of her time working in Birkenau’s notorious Block 10, where women and girls underwent gruesome experiments. She describes exceptional moments of fortitude among the women, such as the makeshift cabarets they put on to lift each other’s spirits. She also describes how she and Zippi helped place Alma Rosé, a well-known Austrian violinist and Jewish inmate, as a conductor of an orchestra made up of Birkenau prisoners.

As much as I hadn’t really seen or understood Auschwitz before, these memoirs began to build a vivid picture of a dark place where light came from the prisoners themselves. In Edith Eva Eger’s memoir, The Choice: Embrace the Possible, the author describes being forced to dance for Dr. Josef Mengele, known as the Angel of Death. “To survive, we conjure an inner world, a haven, even when our eyes are open,” she wrote.

I saw this again and again, as I read the words of survivors. And I thought of my grandparents, and their so-called luck. With each of my grandparent’s memories, I caught glimpses of the family I would never meet. I knew that these faces from their past had kept them going. Their most painful moments were also somehow infused with a deep love for the people they knew. Understanding this, I finally began to see Auschwitz.

Recommended Reading

Approaching an Auschwitz Survivor: Holocaust Testimony and Its Transformations edited by Jürgen Mätthaus

The Nazis Knew My Name: A Remarkable Story of Survival and Courage in Auschwitz-Birkenau by Magda Hellinger and Maya Lee with David Brewster

Protective Custody Prisoner 34042 by Susan Cernyak-Spatz

Rena’s Promise: A Story of Sisters in Auschwitz by Rena Kornreich Gelissen with Heather Dune Macadam

The Choice: Embrace the Possible by Edith Eva Eger

The Auschwitz Volunteer: Beyond Bravery by Captain Witold Pilecki

Eyewitness Auschwitz: Three Years in the Gas Chambers by Filip Müller

I Escaped From Auschwitz by Rudolf Vrba

We Wept Without Tears: Testimonies of the Jewish Sonderkommando from Auschwitz edited by Gideon Greif

Keren Blankfeld’s first book, Lovers in Auschwitz: A True Story will be available in bookstores on January 23. Keren is a freelance journalist whose articles have appeared in The New York Times, Forbes, Reuters, and others. She’s a professor at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism. Originally from São Paulo, Brazil, Keren spent her teenage years in Houston, Texas. She now lives in New York with her husband and two children.