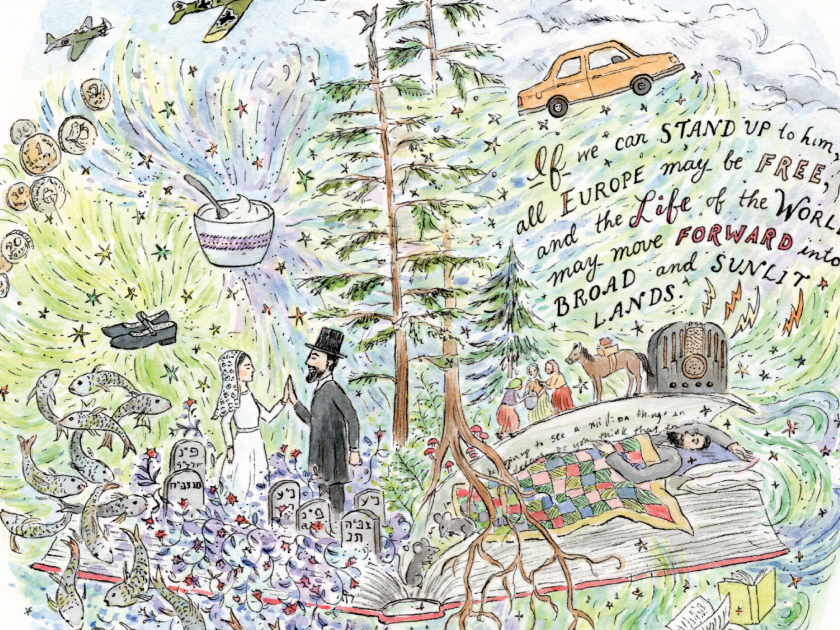

Art by Katherine Messenger

Fresh homemade sour cream, horses and wagons, nice shoes for the Sabbath, and how the Nazis came and murdered almost everyone. These are some of the fragmented memories that Esther Safran Foer heard from her mother about life in the shtetl of Kolki, located in the northwest of present-day Ukraine. “The horrors become familiar with time,” Foer writes in her memoir, I Want You to Know We’re Still Here, “but the banal details can take on an almost magical quality, which might account for the instinct of artists to make the shtetl into a fairy tale.”

I wonder if this instinct to weave magic into retellings of shtetl life stems not from the details themselves, which ultimately aren’t so different from the details of life in small, poor towns in southwestern Ohio or Andhra Pradesh or anywhere: gossip, hunger, communal tensions, religious superstitions. Rather, the impulse to imbue the shtetl with magic may stem precisely from the horrors that eventually befell every shtetl in existence.

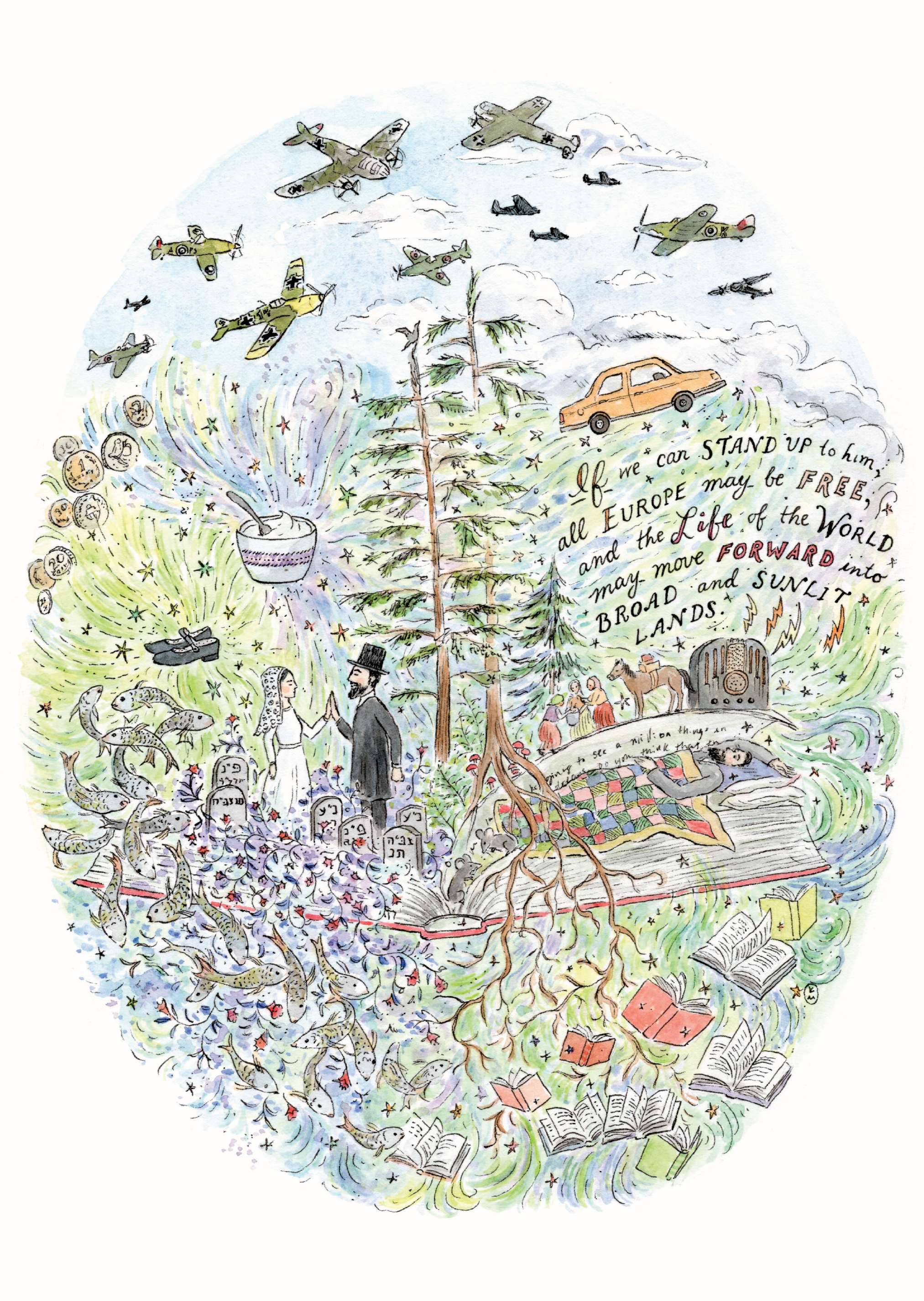

In a recent essay published in The Immanent Frame, “A Wedding in a Cemetery: Judaism, Terror, and Pandemic,” Susannah Heschel describes the practice of the shvartze chasene, the “black wedding” or “plague wedding,” in which shtetl-dwellers would seek to ward off a plague by conducting a marriage, often between neglected and socially marginalized orphans, in the heart of a cemetery. About this practice, she writes, “its weirdness mirrors the horror of an epidemic.” This might speak to the essence of why so much shtetl literature written after the Holocaust employs some version of enchanted thinking: an atrocity of that scale cannot really be processed rationally. (Of the books that were central to my childhood understanding of the Holocaust, one featured a young girl who travels back in time to Auschwitz after opening the door for Elijah at a seder in the 1980s; another depicted a world in which all the Jews are mice.) Art understands the power of catastrophe to obscure itself with its own magnitude: look directly at the sun, and your experience will not be one of vision; the brighter the sun, and the more directly you look, the less you will see. Magic allows the reader to instead glance at one of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s myriad dybbuks, or hope that a shawl might have the power to save a child’s life, as in Cynthia Ozick’s masterful story. Magic allows the reader to ignore, if even just for a moment, the shadow of the sun of mass murder and genocide-yet-to-come that is cast on every aspect of European Jewish history. Perhaps it is through art that we can truly experience all that existed before catastrophe — the time in which catastrophe was only one of many possible futures.

Authors of shtetl literature, of course, are not the only ones to turn to the surreal when grappling with human atrocities of incomprehensible scope and savagery. From Toni Morrison in Beloved to Octavia E. Butler in Kindred; from Colson Whitehead in The Underground Railroad to Ta-Nehisi Coates in The Water Dancer, authors have often engaged with the genocidal reality of American slavery by incorporating the fantastical or the unreal, in a narrow sense of the term. (Toni Morrison was notably reluctant to apply the term “magic realism” to her work, precisely for the way in which it can dilute or deny the reality of this literature.)

Historian Michael André Bernstein writes about “backshadowing” — the practice of writing apocalyptic history as though what happened was a foregone conclusion. Speaking of a Holocaust that had yet to come to every shtetl, as I did above, is a flagrant example of such backshadowing. Bernstein’s emphasis on the danger of the backshadow resonates on an ethical level. (If the Nazis were destined to come to power, should we see all efforts at resistance as futile?) Nevertheless, when I read the word “shtetl” in a work of history or memoir, I think about the suffering and murder that is yet to come for its residents. Magic in some shtetl fiction written after the Holocaust can provide readers with a way to deflect the backshadow, even temporarily; if you are uncertain of the parameters of the world you are entering, then perhaps catastrophe is not the only possible outcome for every character you encounter.

The impulse to imbue the shtetl with magic may stem precisely from the horrors that eventually befell every shtetl in existence.

Art by Katherine Messenger

Ramona Ausubel’s 2012 novel, No One Is Here Except All of Us, takes place in Zalischik, a village with only one hundred residents. (Although it is not explicitly labeled as a shtetl in the novel, Ausubel explains in the author’s note that it resembles the real Romanian shtetl of the same name, from which parts of her family hailed.) Magic, at least in the sense of the not-strictly-real, is present in this book from its earliest chapters. The story starts with the residents of Zalischik gathering for a Sabbath service in “the healer’s” living room, but the service never gets underway: instead of praying, the healer begins by reading to everyone from a weeks-old newspaper that announces the outbreak of war, and then — as a military airplane passes overhead and the villagers descend into panic — moves on to read from Genesis. Later the same evening, alongside “slapping fish … curled up like question marks,” a nameless stranger washes up on Zalischik’s shore. She is the sole survivor of a massacre somewhere upriver, and the villagers wonder if she is a prophet. Her strange arrival sparks them to collectively decide to “start over,” to pretend that there is no world around them, to retell their story such that it might not end with mass murder. “No one exists but us and God?” says the narrator, Lena, who is then eleven years old. “Everything is still to come?”

The first half of the book delves into the phantasmagorical minutiae of Zalischik’s efforts to will the real world out of being — efforts that at first seem successful, or successful enough that life can continue to flow through Zalischik’s own currents of oddness and unpleasantness without the Nazis looming around every corner. In this new world, for example, Lena’s aunt and uncle, unable to have children of their own, ask Lena’s parents for one of theirs. Lena is given to them, and they pretend, to deeply disturbing effect, that she is a baby, who turns a year or so older every few weeks. Still a child, but deemed “grown” after some such months, Lena is married off to a boy a few years older than she, Igor. They have a son, Solomon, and then another son who is never named. Igor takes to sleeping for most of the day, feeling that “his purpose was to rest for all of us.” The world outside seems to cease its turning.

But despite these singularities, there is such a sense of foreboding throughout the first half of the book — “As the rest of the continent’s towns and villages were emptied out, ours grew more and more peaceful” — that there is almost a sense of relief when the spell breaks. The stranger finds and turns on a radio, and the real world, heralded by a Winston Churchill speech, comes rushing back into the frame. The second half of the novel follows a more familiar Holocaust trajectory (aside from a semi-enchanted subplot in which Igor is kidnapped by fairly friendly Italians and kept as a prisoner in an otherwise empty jail on an idyllic island, doted on by the jailer, the jailer’s mother, and others). Almost everyone in Zalischik drowns, starves, or is tormented or murdered. In the end, magic does not stave off genocide or otherwise alter history. The version of shtetl life depicted in the book’s first half is obscured by the horror that ultimately strikes all of the characters in the second half.

____

The 2020 novel The Lost Shtetl by Max Gross also grapples with magic and backshadows, with reality and unreality and what lies between the two. But here it is not the shtetl that is tinged with magic while the outside world is afflicted with the grim brightness of the “real.” Instead, it is the opposite. Kreskol, the shtetl at this novel’s core, is nestled — like Ausubel’s Zalischik — in a dense Eastern European forest. Through a series of bureaucratic missteps and petty grudges, Kreskol was “lost” to the rest of Poland and, eventually, to the rest of the world — the Nazis did not find it, nor did the Soviets after them. (If this scenario stretches the limits of some readers’ belief, those readers may find their skepticism reflected in Gross’s character Professor Zbigniew Berlinsky, who appears halfway through the novel to cast doubt on Kreskol’s history. His paper, read aloud at a conference at Bar-Ilan University, inadvertently sets off a series of antisemitism-drenched court proceedings and media campaigns seeking to “unmask” the schemers of Kreskol — who, many people begin to believe, must be carrying out an intricate plan to receive reparations from the Polish state.) However, unlike the Zalischik villagers, the residents of Kreskol haven’t intentionally been hiding; they have simply been abiding by a calcified tradition of not leaving. Most are entirely unaware of the Holocaust from which they were spared, and of twentieth-century modernity itself. And that is how we encounter this shtetl, circa 2020. Kreskol’s spell is broken early in the novel, when a marital crisis leads both members of an unhappy couple to disappear, separately, into the forest. A marginalized orphan named Yankel Lewinkopf — perhaps of the type who would have been selected for a shvartze chasene—is sent to look for them in the nearest city, Smolskie. What he begins to discover on his journey strikes him as utterly enchanted. Seeing a car for the first time, he exclaims, “It’s being pushed along by magic!” (Later, when the rest of Kreskol is “discovered,” residents are convinced that the Polish official’s offhand comment about the next day’s weather is an indication that he is a sorcerer or wizard.)

The residents of Kreskol haven’t intentionally been hiding; they have simply been abiding by a calcified tradition of not leaving. Most are entirely unaware of the Holocaust from which they were spared, and of twentieth-century modernity itself.

There is no backshadow for Yankel; he knows nothing of what has happened in the world for the past hundred years. When he is institutionalized in a Polish mental hospital, it falls to a local professor, Johann Fishbein, who speaks some Yiddish, to tell Yankel about the Holocaust. When the professor finishes his toned-down description of that chapter of history, explaining in general terms that the majority of Jews not only in Smolskie or Poland but in all of Europe were murdered, Yankel responds, “Not to be disrespectful, Dr. Fishbein, but just how dumb do you think I am?” And so, when the Holocaust finally does enter the book in more detail — through the story of a one-eyed Aramaic teacher named Leonid Spektor, who survived the Nazis and found his way to Kreskol — the reader is able to hear about it almost as if for the first time. It is recounted not as a story crowded with backshadows, a story that had to happen, but rather simply — and so horrifically that it should strain belief — something that did happen.

The magic-adjacent device of an alternative reality allows for the backshadow to be lifted from the shtetl, for the characters’ longings and lusts and ludicrousness to be the central focus of the novel, with no genocide yet to come. In a sense, this book and others like it are not only portraits of what could have been: they are also portraits of what is. While the shtetl may no longer exist in physical form, it continues to survive in the forests of the literary imaginations of Esther Safran Foer, Ramona Ausubel, Max Gross, and other writers in the twenty-first century.

Moriel Rothman-Zecher is the author of the novel Sadness Is a White Bird (Atria Books, 2018), which was a finalist for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize and the National Jewish Book Award, among other honors. His second novel, which follows two Yiddish speaking immigrants from a fictional shtetl to Philadelphia of the 1930s, is forthcoming from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Moriel’s work has been published in The New York Times, the Paris Review’s Daily, Zyzzyva Magazine, and elsewhere, and he is the recipient of the National Book Foundation’s ‘5 Under 35’ Honor, two MacDowell Colony Fellowships for Literature (2017 & 2020), and a Wallis Annenberg Helix Project Fellowship for Yiddish Cultural Studies (2018−2019). Moriel lives in Yellow Springs, Ohio, with his family.

Moriel is the creator of the fictional characters Mathew L. Cohn, Marky Miller, and M. Pinsky-Appelbaum as part of the series, What We Talk About When We Talk About the Golem.