Posted by Naomi Firestone-Teeter

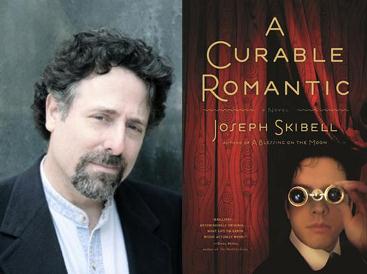

Our third installment of “Words from our Finalists”…Joseph Skibell

Our third installment of “Words from our Finalists”…Joseph Skibell

Joseph…meet our Readers

Readers…meet Joseph

What are some of the most challenging things about writing fiction?

What did Hemingway say in his Paris Review interview with George Plimpton? “The hardest thing about writing is getting the words in the right order.” Typical Hemingway brevity, but that does seem to cover it.

What or who has been your inspiration for writing fiction?

What or who has been your inspiration for writing fiction?

Inspiration comes from everywhere. In the last two weeks, I saw a production of Sam Shepard’s “Buried Child” and I heard the master guitarist Pierre Bensusan play. The creative generosity of both Shepard and Bensusan reminded me of what art can really do when it’s honest and it comes from an open and pure heart. I find that very inspiring. Being moved by their work makes me want to continue working and trying to inhabit that same open and honest space.

Who is your intended audience?

Who is your intended audience?

Perhaps I should be a little more ambitious, but I try to write for the entirety of the literate world. And I’m hoping that members of the literate world will read my books to members of the non-literate world. I’m sometimes saddened that adult readers, unlike their “young adult” counterparts, seem fairly unadventurous, that fiction that deals with small, domestic issues, preferably in the mode of realism, seems so much more palpable to these adult readers than do daring, ambitious “ill-behaved” books that take on bigger issues in a more playful, ferocious or rambunctious style.

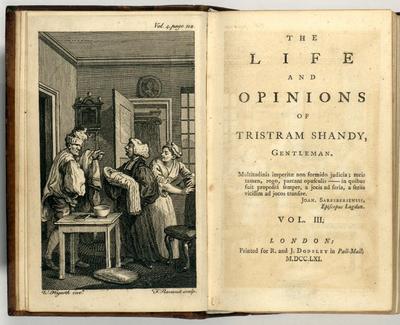

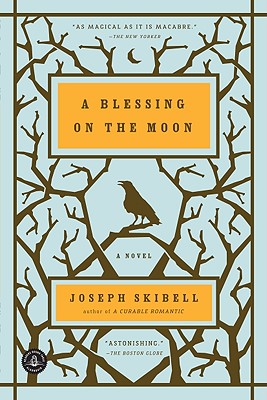

Milan Kundera calls these “ill-behaved” books “the children of Tristram Shandy” as opposed to the “well-behaved” books, which he calls “children of Clarissa.” Rushdie’s Midnight Children, Grass’s The Tin Drum,Kundera’s own Book of Laughter and Forgetting, the novels of Beckett, Kafka and Bellow all fall into this category of ill-behaved books, as do my A Blessing on the Moon and A Curable Romantic.

Milan Kundera calls these “ill-behaved” books “the children of Tristram Shandy” as opposed to the “well-behaved” books, which he calls “children of Clarissa.” Rushdie’s Midnight Children, Grass’s The Tin Drum,Kundera’s own Book of Laughter and Forgetting, the novels of Beckett, Kafka and Bellow all fall into this category of ill-behaved books, as do my A Blessing on the Moon and A Curable Romantic.

Are you working on anything new right now?

I have a short list of new projects, but nothing that can be spoken about yet, really. I think I’ve found the subject for my next novel, and I’m excited about that, and it’s going to be very different from the other three books.

What are you reading now?

What are you reading now?

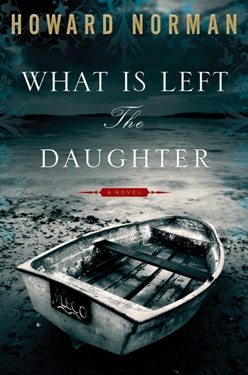

The novel I’m urging onto anybody who will listen is Howard Norman’s What is Left the Daughter. Norman is one of our finest novelists with a singular and idiosyncratic voice. He’s unpretentiously gifted, and this book is one of his best. I’m planning on reading it again, actually. I don’t quite understand how he achieves the effects he achieves. The book is so moving, but it’s hard to say why. His work has that same honesty and purity I mentioned finding in the Shepard’s play and in Bensusan’s playing. A spirit of childlike play, I guess, combined with a hungry intelligence and an artful sense of integrity.

When did you decide to be a writer? Where were you?

I was in Mr. Bravenec’s sixth grade class at Geo. A. Rush Elementary School in Lubbock, Texas, when I read Anthony Scaduto’s biography of Bob Dylan. According to Scaduto, Dylan read John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row as a kid and was so turned on by it that he read all of Steinbeck’s work after that. At the time, I wanted to grow up to be Bob Dylan, so I thought I should probably do everything Bob Dylan did as a child in order to realize this ambition. I got a copy of Cannery Row out of the library and I read it, and I was so turned on by it, I read everything that Steinbeck had written, also. By the time I was done, though, I no longer wanted to be Bob Dylan. I wanted to be John Steinbeck.

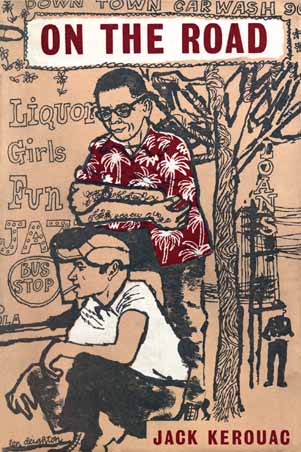

Later, during his Rolling Thunder Revue Tour, Dylan visited Jack Kerouac’s grave. I read about this in Rolling Stone Magazine. I’d never heard of Jack Kerouac, but I bought a copy of On the Road, and then I read all of Kerouac’s work, which I also found inspiring.

Later, during his Rolling Thunder Revue Tour, Dylan visited Jack Kerouac’s grave. I read about this in Rolling Stone Magazine. I’d never heard of Jack Kerouac, but I bought a copy of On the Road, and then I read all of Kerouac’s work, which I also found inspiring.

Still, I didn’t think I could be a novelist, because — especially after reading Steinbeck — I thought a novelist had to know how to brush out a horse and repair a motor and dissect mollusks and things like that. But then I read Voltaire’sCandide – I was in the seventh grade; I remember reading it during my algebra class – and I thought to myself: Hey, I could write a book like this. I mean, there are no animals in Candide, no one repairs a motor, there’s no science, there’s barely a landscape.

So, really, I have Bob Dylan to thank for all of this, I guess. Thanks, Bob.

What is the mountaintop for you — how do you define success?

It’s easy to get sidetracked by big advances and awards and being on bestseller lists and things like that. Writing can be such a lonely pursuit, and I know so many writers who end up craving those things, just so they know that there’s somebody out there who actually cares about what they’re doing. So I try to remember why books were important to me in the first place.

I think it’s the same with really great writing. When someone like W.B. Yeats says, “Hearts are not had as a gift but hearts are earned,” or Jackson Browne describes Culver City as a place “where the ghostly specter of Howard Hughes/hovers in the smoke of a thousand barbeques,” you think to yourself, “Man, that’s about as good as it gets.” I mean, these are writers whose use of words and thoughts and observations and emotions and meter and sound is as astonishing and as inspiring as the physical stuff Shaun White can do on a snowboard.You know, when you see somebody like Shaun White do something really amazing on a snowboard, you kind of empathize with him. He sort of stands in for all of humanity. You think, “Wow, it’s amazing that he can do that,” but you’re also thinking, “Wow, it’s amazing that a human being can do that.”

I think it’s the same with really great writing. When someone like W.B. Yeats says, “Hearts are not had as a gift but hearts are earned,” or Jackson Browne describes Culver City as a place “where the ghostly specter of Howard Hughes/hovers in the smoke of a thousand barbeques,” you think to yourself, “Man, that’s about as good as it gets.” I mean, these are writers whose use of words and thoughts and observations and emotions and meter and sound is as astonishing and as inspiring as the physical stuff Shaun White can do on a snowboard.You know, when you see somebody like Shaun White do something really amazing on a snowboard, you kind of empathize with him. He sort of stands in for all of humanity. You think, “Wow, it’s amazing that he can do that,” but you’re also thinking, “Wow, it’s amazing that a human being can do that.”

And because of writing like this, you actually experience something you wouldn’t have been able to experience otherwise, and it’s something you wouldn’t have been able to experience in any other way.

So I guess, for me, that would really be the mountaintop, or the pinnacle of success – knowing that your work is speaking to another person in a way that reverberates with their concerns and their lives in a meaningful way.

How do you write — what is your private modus operandi? What talismans, rituals, props do you use to assist you?

The discipline of writing every day is so intensely focused that I have next to no memory about the process itself, though it seems to involve a Cross pen, an AMPAD legal-size “Evidence” pad – 100 sheets, Canary yellow, Wide Ruled, 8½” x 14” with a double-thick back for extra support (these are harder and harder to come by these days) – a chair, a desk, and a hot beverage, sometimes coffee, sometimes tea. I try to keep a very low page count every day, so that doing the work always remains enjoyable.

What do you want readers to get out of your book?

What do you want readers to get out of your book?

With A Blessing on the Moon, I wanted to speak to the reader so deeply that the book enters the reader’s dream-life, and I’ve been told on many occasions, by readers, that this is how the novel works. With The English Disease, I simply wanted to make the reader laugh.

A Curable Romantic was a bit different. WithA Curable Romantic, my hope was that Dr. Sammelsohn, the novel’s protagonist and narrator, would seem like a sweet and endearing friend accompanying the reader wherever he or she went for the few weeks it takes to read the book.

At heart, I hope my novels work as a kind of cure for that deep loneliness I imagine we all feel, the writer’s voice whispering intimately into the reader’s inner ear, speaking about the most essential things: love, family, death, hope, desire, dreams.

You can read more about Joseph Skibell by visiting his website: http://www.josephskibell.com/

Originally from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Naomi is the CEO of Jewish Book Council. She graduated from Emory University with degrees in English and Art History and, in addition, studied at University College London. Prior to her role as executive director and now CEO, Naomi served as the founding editor of the JBC website and blog and managing editor of Jewish Book World. In addition, she has overseen JBC’s digital initiatives, and also developed the JBC’s Visiting Scribe series and Unpacking the Book: Jewish Writers in Conversation.