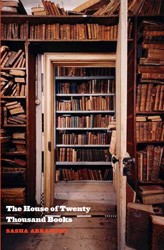

Sasha Abramsky is the author of The House of Twenty Thousand Books, a memoir exploring his grandparents’ lives through their vast literary collection in London. He will be blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council’s Visiting Scribe series.

I have been a journalist for nearly a quarter of a century, and have, over the years, interviewed thousands of people. Yet my most recent book, The House of Twenty Thousand Books—a book that is, on one level, simply about the lives lived by my father’s parents; on another level a journey through the modern Jewish experience; and, on yet another level again, a portrait of obsessions — took me on an intellectual odyssey the likes of which I doubt I’ll ever again experience.

Writing The House of Twenty Thousand Books, for several years I immersed myself in the worlds, the dreams, the hopes and the fears lived by others. It’s a strange sensation. In some ways, the realities of those others became more real than were my own. The political passions, the bibliographic obsessions, the conversations of my grandparents and their friends and comrades, became the fabric of my daily life. I trained my mind to effortlessly wander bookshelves, containing thousands of books on both socialist history and on Jewish history, that had been emptied several years earlier, following my grandfather’s death; and I asked my palette to virtually re-taste culinary marvels conjured up by my grandmother Mimi in her kitchen a generation ago, to feed the many, many people who would descend on the House at 5 Hillway in north London for meals and conversation each and every evening for roughly half a century.

There is something extraordinary about the sensory experience that accompanies memoir writing. For no matter how much research you do, no matter how many archives you enter and old men and women you interview, at its core the project is a sensory one. It is about recreating what people whom in my case I only ever knew once they were elderly, once they were simply “grandparents,” looked like and smelled like, sounded like and acted like, the texture of their skin, or even something as intimate as how their dandruff fell onto the shoulders of their shirts, and about how these things changed over time as the people one is writing about journeyed the arc of their own lives. It is about learning to understand the old as they were when they were young, then again as they were in middle age, and to realize the immense inadequacy of reducing complex humans, who lived full lives, simply to the label “grandparents.”

For me, writing about a house filled floor to ceiling with rare books, it became a memory game about what individual tomes looked like, what aromas their old paper gave off when opened up, what different bindings and different materials felt like to the touch; the difference between the thick acid-free papers of the past and the thinner papers of twentieth century mass production; the extraordinary difference between paper and parchment, and, in turn, parchment and vellum.

Ultimately, my writing project became a series of daily conversations in my head about why this particular book was deliberately placed next to that particular book — and in asking that question, trying to draw a whole set of intellectual conclusions, about the ways in which ideas connected, the places and periods that my grandfather Chimen was drawing together in his mind’s‑eye through the architecture of his extraordinary library.

There’s something almost mystical in the memoir-writing experience. I came to think that certain places retain an almost ghostly fragrance, an invisible film, of past occupants and events; and that, with enough concentration, one can briefly make visible, make tactile again, what is ordinarily hidden by time. When I got deep enough into that strange place, where past and present mingle, I found that the writing came naturally, in a flood. I was no longer a middle-aged man in the second decade of the twenty-first century, but was able to imagine myself rather a child again, in the 1970s and 1980s, surrounded by my grandparents, their relatives, their friends, and their books. It was a strange place to be, a place outside of time, a place where — I eventually feared — one could get stuck. But it was also a place that provided me space to write, and then to write some more, until, eventually The House of Twenty Thousand Books was complete.

Sasha Abramsky grew up in London and attended Balliol College, Oxford, where he studied politics, philosophy, and economics. He is a Senior Fellow at Demos think tank and teaches writing at University of California Davis. His memoir The House of Twenty Thousand Books is now available from New York Review Books.

Related Content:

Sasha Abramsky grew up in London and attended Balliol College, Oxford, where he studied politics, philosophy, and economics. Abramsky is a journalist and author whose work has appeared in The Nation, American Prospect, The New Yorker Online, and many other publications. His most recent book, The American Way of Poverty: How the Other Half Still Lives, was listed by The New York Times as among the one hundred notable books of 2013. He is a Senior Fellow at Demos think tank and teaches writing at University of California Davis. Abramsky lives in Sacramento, CA with his wife and their two children.