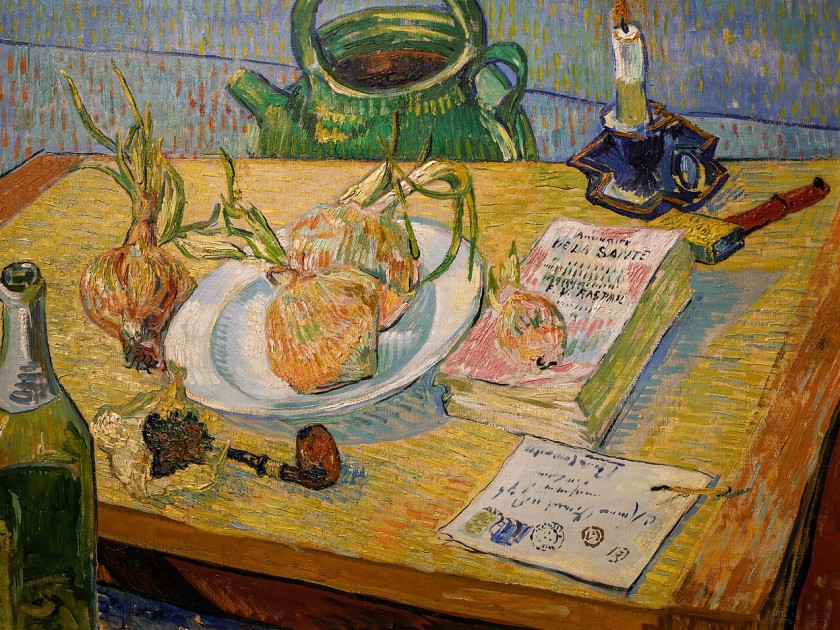

Still life with a plate of onions, Vincent Van Gogh, 1889

Kröller-Müller Museum

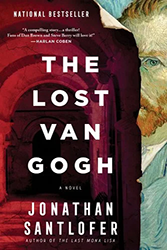

Researching a novel always leads me to unexpected places and discoveries. In the case of my most recent novel, The Lost Van Gogh, the subject I found myself immersed in was looted art and art restitution, topics very much in the news today, and a complex moral dilemma for museums and collectors. In the novel, I trace the story of one painting hidden by the French Resistance in a unique way, and found by my protagonists, Luke and Alex, eighty years later, only to have it stolen again. Their ensuing hunt takes them across the globe – from New York to Amsterdam – and finally to Auvers-sur-Oise, France, where Vincent Van Gogh spent his last seventy days. Working along with Luke and Alex (and sometimes against them), is INTERPOL agent John Washington Smith, all three risking their lives as they come up against the people who traffic in illegal art, some who will stop at nothing – not even murder – to protect their investment. Though the novel mixes fact and fiction, the ruthless and immoral art dealers portrayed in the story are based on real-life examples.

The Nazi plunder of art was unlike any art theft before or since. The scale of theft was enormous, systematically undertaken, and heavily documented, one-fifth of Europe’s art was stolen, with over 100, 000 pieces still missing today. As the Nazis occupied one country after another, lists were compiled, and prominent Jewish art collectors targeted. Collections were sold under duress, a gun held to the owner’s head as they signed “bills of sale,” and compensation sent to bank accounts that were immediately frozen.

The Third Reich had a perverse relationship to art, stealing both what they liked (representational and classical German art), and what they did not, which they labeled degenerate (modern art, and art made by Jews, artists of color, or homosexuals), the latter artwork sold to support the Nazi war effort or was destroyed in bonfires.

While Hitler accumulated art for the Führermuseum (which he planned to build in his hometown of Linz, Austria), other high-ranking Nazi officials like Goring and Goebels stockpiled stolen art for their own private, often vast, art collections.

When the war ended, the Monuments Men was formed, a group of 345 art historians, curators, and art specialists, who worked to return Nazi-looted art to the countries from which it had been stolen. The country, not the individuals. Created in 1943, it was disbanded in 1946, long before the job was done.

The stories of heirs trying to piece together art collections belonging to grandparents and great-grandparents are numerous and heartbreaking. Even the Jewish collectors who moved in the highest strata of German society, who felt safe and protected by their wealth, were ultimately murdered for their art. In many cases, these families had converted to Christianity with little or no knowledge of their Jewish heritage.

A lesser-known fact is that Fluchtgut, or “flight assets” which refers to art sold by Jews under duress, is still traded. Many of the art dealers who acquired and sold stolen art during the war (for which they were never held accountable or put on trial), continued to do so after, and some of their heirs continue to do so today.

The Nazi plunder of art was unlike any art theft before or since. The scale of theft was enormous, systematically undertaken, and heavily documented, one-fifth of Europe’s art was stolen, with over 100, 000 pieces still missing today.

Case in point, Cornelius Gurlitt (son of Hildebrand Gurlitt, one of Hitler’s four appointed art dealers), came under suspicion on a 2010 trip from Munich to Zurich, when a routine check revealed he was traveling with $10,000 in cash. This led to further investigation and finally, in 2012, to a search of his Munich apartment. There, 1,500 pieces of art were discovered, including work by Picasso, Matisse, Monet, and Renoir, among others. Many were Nazi-looted and missing since the end of war; Gurlitt’s story a clear example that such illegal art dealing has continued long after the war ended.

All of this plays out as an integral part of The Lost Van Gogh, a thriller with serious issues at its core. With the aid of a contemporary Fluchtgut hunter, my three protagonists, Luke, Alex, and Smith, track down the lost Van Gogh self-portrait, and in discovering the painting’s origin, come to a tragic realization: that every Nazi-stolen painting represents a stolen life.

I took my cue from legendary Hollywood film director and screenwriter Billy Wilder, an Austrian-born Jew, whose family died in concentration camps. Wilder (who moved to Paris after Hitler’s rise to power, and later to Hollywood), was hired by the US Army to film the liberation of the camps. When he screened his documentary, Death Mills, in Berlin, half the audience left, the other half were stunned into silence. What Wilder took from this experience was the need to entertain if you wanted to show the truth. As he often said, the tougher the material the more you’d better make them laugh.

I was not looking for laughs in The Lost Van Gogh, but my intent was to entertain, to create a page-turning novel while shining a light on one of history’s darkest eras.

As I write this, Nazi-looted Egon Schiele watercolors are about to hit the auction block, their combined value several million dollars. Fifty percent of the sale proceeds will go to the heirs of the original owner, Fritz Grünbaum, a Jewish cabaret performer who died in Dachau in 1941. During his detainment, Grünbaum was forced to sign a power of attorney document and surrender his artworks, which were subsequently parceled off and sold to benefit the Nazi Party. Grünbaum’s heirs plan to put their share toward a scholarship program for young musicians.

Santlofer is the author of six bestselling novels, among them The Death Artist, and Nero award-winning Anatomy of Fear. His memoir, The Widower’s Notebook, received national acclaim and was featured on NPR’s Fresh Air with Terry Gross. He is the editor/creator of seven anthologies, the recipient of two NEA grants, Visiting Artist at the American Academy in Rome, and serves on the board of Yaddo. He is a noted speaker.