Nina Siegal grew up in New York City and Great Neck, Long Island, but these days she lives in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, where she works as an author and a frequent contributor to the International New York Times. Her most recent novel, The Anatomy Lesson, is now available. She will be blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning.

Recently, a journalist who was interviewing me asked me to describe what it felt like to be a Jewish New Yorker living in Amsterdam. She put it this way: “Is it okay for you there?” As it happens, the interviewer was a Dutch Jewish woman who had moved to New York, where, she confessed to me, she felt a lot more “at home.” “It’s hard to be Jewish in Amsterdam,” she said.

Recently, a journalist who was interviewing me asked me to describe what it felt like to be a Jewish New Yorker living in Amsterdam. She put it this way: “Is it okay for you there?” As it happens, the interviewer was a Dutch Jewish woman who had moved to New York, where, she confessed to me, she felt a lot more “at home.” “It’s hard to be Jewish in Amsterdam,” she said.

It was interesting to me that she put it that way. So many of the Dutch people I’ve met here are always saying what an open, tolerant, international city Amsterdam is, and how Jews have always been so welcome here. But the truth is, I’ve never been able to say that I’ve felt “at home” as a Jewish person in Amsterdam, though I have been living here for the last eight years and in many other ways I do feel at home.

I came here in 2006 to begin research for my second novel, The Anatomy Lesson (Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 2014), which takes place in this city on one day in 1632, and tells the imagined story behind Rembrandt’s first masterpiece. I rented my first apartment in the part of the city where Rembrandt used to live, which is known as the Jodenbuurt, or Jewish quarter. The Rembrandt House Museum, in Rembrandt’s former home, is on the Jodenbreestraat, or Jewish Broadway.

Ever since the sixteenth century this quarter of the city, outside of the Centrum, had been a sanctuary for Jews fleeing persecution first from Portugal and Spain, and later from Central and Eastern Europe. For a long time, scholars used to insist that Rembrandt was a friend to the Jews because he lived in this neighborhood and painted portraits of a famous Amsterdam rabbi and several Old Testament scenes here, but more recently that history has been called into question.

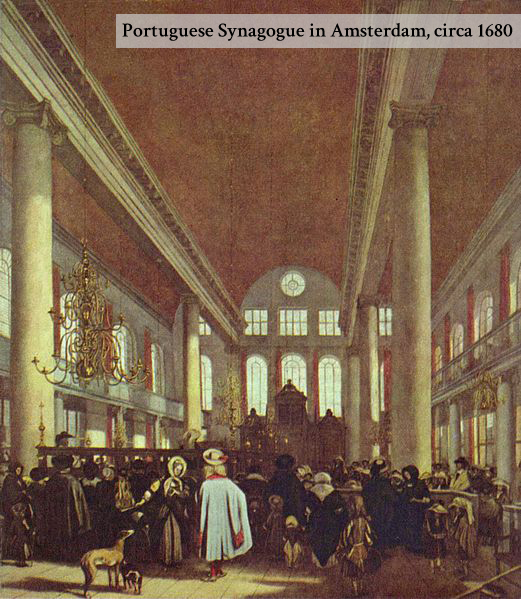

This is the neighborhood where Baruch Spinoza lived and worked. There are five synagogues in that neighborhood on a single block, including the awe-inspiring seventeenth-century Portuguese Synagogue, and four other synagogues that now comprise the Amsterdam Jewish Museum, a temple to a tragic history.

Amsterdam was indeed once known as city that was welcoming to Jews, who were granted citizenship as early as 1616; for years the city was known as “Mokum” the Hebrew word for “place.” And of course everyone knows the story of Anne Frank, Amsterdam’s most famous Jew, who was also a German Jew whose family moved here to get away from the Nazis – unsuccessfully, of course.

Some people still call it Mokum, and the Dutch national soccer team, Ajax, is still (in rather poor taste I think) still known as “the Jews.” But most of the Jews are gone now. About 90 percent of the Jewish population of the Netherlands perished in WWII, the highest percentage loss of a national population in all of Europe, according to the Columbia Guide to the Holocaust.

The Jewish community, such as it is, is now centered in the southern part of the city, and walking through Rembrandt’s old neighborhood feels like walking through a ghost town, with many of the Jewish buildings denuded of their former cultural purpose, or turned to memorials. Lots of the buildings in the district are new, too, and that’s because after the Jewish families were rounded up here, their homes were looted and ransacked to the extent that even the lumber was stripped from their walls and floors by desperate Amsterdammers during the Hunger Winter of 1944 and 45. They were in such a bad state that they had to be torn down.

Strangely, the experience of living and working in that neighborhood made me feel more Jewish than I had ever felt growing up in New York and Great Neck, in two very busy Jewish communities, surrounded by Jews. I have always called myself a “secular, cultural Jew,” who feels connected to Jewish life, but doesn’t practice any form of observance. I have no Dutch ancestry, as far as I know, but my mother’s side of the family was from Hungary and Ukraine. Most of my mother’s relatives in Hungary died in Auschwitz; my grandfather survived three concentration camps, and was liberated from Mauthausen. Those were the two camps where most of the Dutch Jews were killed as well.

Surrounded by a completely destroyed Jewish community, I started to feel the power and weight of an absence I had only ever imagined or read about in books. In place of a vibrant Jewish community holding services in the beautiful local temples, there were historical artifacts documenting those disappeared customs and people. Where there used to be a lively Jewish theater, filled with actors, musicians and laughter, there is now an empty shell of a building filled with a memorial wall and a single burning flame.

Over time, being in the Jodenbuurt engendered in me a deep sense of longing for a community I never knew. It made me long, too, for the community of easy Jewishness that I’d left behind in New York, where there were still people simply being alive, being Jews.

In answer to the interviewer’s question, I had to confess that somehow being here in Amsterdam helped me connect with some part of the reality of being a Jewish person. Not to connect to the culture that I had come to know as Jewish culture, but to come into contact with the element of our history that is absence, disappearance, and devastation. That is still very real here in Amsterdam, as it is in other parts of Europe, too, even if there are few people who want to talk about it anymore today.

None of that made it into the Rembrandt novel, but it will be part of my next book, a project I’m beginning to embark on now.

Nina Siegal got her B.A. at Cornell University and her M.F.A. in Fiction at the Iowa Writers Workshop. Although she has written extensively about women in US prisons, housing and homelessness, and all sorts of urban cultural issues, Siegal lately focuses on the intersection of art and society, which is also the theme of both her novels. Read more about her here.

Related Content:

- Ashes in the Wind: The Destruction of Dutch Jewry by Dr. Jacob Presser

- The Elixir of Immortality by Gabi Gleichmann

Nina Siegal received her MFA in fiction from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and was a Fulbright Scholar. She has written for the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times, among other publications. She lives in Amsterdam.