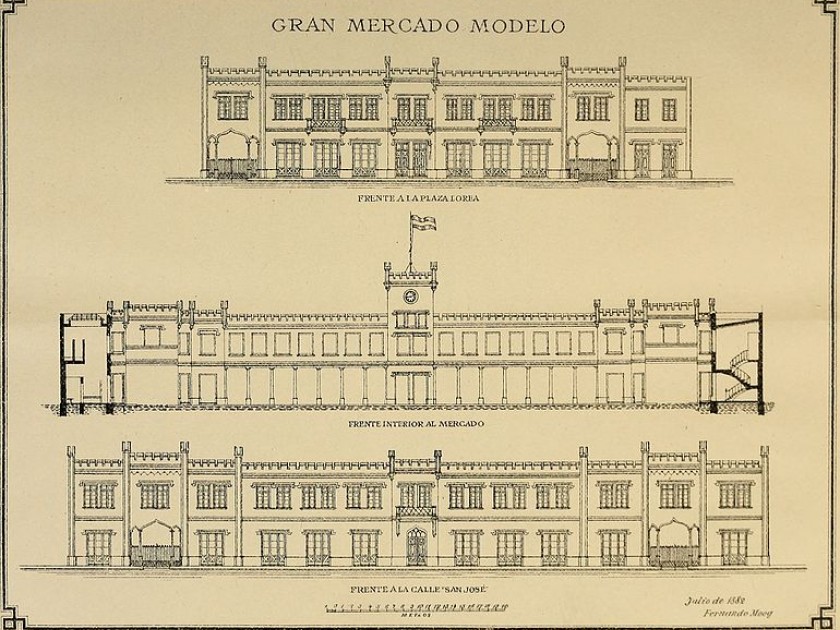

Congreso Científico Internacional Americano (Buenos Aires, Argentina), 1876, by Sociedad Científica Argentina.

A frequent question asked by readers and acquaintances is, “Where do you get your ideas?”

It reminds me of how at age twelve, a friend and I tried writing stories with prompts like “The little girl’s mother didn’t return home….” I wasn’t particularly good at that, and never finished a memorable story.

Decades later, though, after life’s vicissitudes shook me, social injustice raised my indignation, and human nature presented me with all its ugliness, I needed no further prompts to write stories.

As a business woman with an education in economics, I had been working for years on women’s issues. Believing that economic freedom was the first of all freedoms, I volunteered for the Small Business Administration’s women entrepreneurial programs and watched as, in the USA, financial independence gave a woman the courage to leave an abusive marriage. In an African village, she could realize her vision of a school for girls.

And then I attended the 1995 International Women’s Conference in Beijing, where I led entrepreneurial workshops and participated in economic panels. On my second day, I was shocked to my core by accounts of clitoridectomy of tens of millions of Muslim and African women, and the Indian “burning of the brides” over family dowry disputes. In the coming days I learned of Chinese gendercide — singling out baby girls for death — and about the way our US justice system betrayed molested children by giving custody to their molesters. I learned of mass rape as a tool of war to break a nation’s spirit, and of how the Japanese Imperial Army captured thousands of girls during WWII as “comfort” sex slaves to its soldiers, yet steadfastly refused to acknowledge this war crime.

My world was shaken of its illusion that financial independence was the first independence, because I had taken for granted the real first freedom — the freedom from violence against women.

I closed my five-city marketing firm, canceled the multi-phone lines, and donated my business suits to charity. In the new silence I let the voices of courageous girls and women fill my head, channel through me into the tips of my fingers, and come out in the form of novels as I set out on the lonely and treacherous journey alongside one protagonist at a time. The stories were all around me. Skeletons were hiding in all corners of our society — all over the globe — often in full sight. Each time I finished a novel, the next one presented itself, taking hold of my head and heart, and compelling me to sit down to what turned out to be three to six years’ work at a time.

My world was shaken of its illusion that financial independence was the first independence, because I had taken for granted the real first freedom — the freedom from violence against women.

The process continues. Working now on my sixth novel, I’ve realized that the seeds of every story sprouted roots years earlier. All it takes is a passing comment, a line in a newspaper, or a road sign, and the idea blooms. It grabs me and doesn’t let go until I crawl under the skin of a new protagonist. I rise and fall with her spirit as she struggles against the forces that shape her life, be they psychological, political, social, geographical, legal, economic, or religious.

The process of writing for me is like being in a dream: it feels real — I see the sights, inhale the smells, and hear the sounds. But unlike the trance world of a dream, the story remains rational. In time, I learned to observe my own brain as it thinks in multi-layered plots, where characters are subject to the above-mentioned forces working either in concert or against one another. The scenes are often so heart-wrenching that I find myself sobbing while my fingers furiously tap the keyboard.

Crying is good for the reader, too — I realized that early on — but only if it is relieved by moments of triumph and exhilaration. Indeed, as I mastered the craft of fiction writing, I became forever mindful of the emotional roller-coaster required of both the writer and the reader. Once I grab my reader’s attention with the opening scene, or the first several pages, she falls asleep for the night, my book tossed on the floor. She doesn’t get back to it until perhaps the next evening, after a full day of dealing with a boss’s demands, fighting with her mother on the phone, overspending at the beauty counter, rushing to get stitches on a child’s gashed chin, fretting about a pile of dirty laundry, or being aggravated when her car overheats while stuck in traffic. Throughout her turbulent day I hope that my hold on her is so tight that she wonders time and again what will happen next. Then, when she finally falls back into bed, exhausted, I must make sure that she wants nothing more than to pick up my story where she’s left it.

Indeed, as I mastered the craft of fiction writing, I became forever mindful of the emotional roller-coaster required of both the writer and the reader.

I, Talia, am not in any of my novels; I feel no need to dissect my life and serve it on a platter, while, like an actress on stage, I enjoy entering into another person psyche. But I need not invent the emotions I bring to each novel — the power of motherhood, the pain of a traumatic childhood, the quest for personal growth, the anguish of filial responsibility, the joy of love, or the struggle against social norms.

Author Paul Gallico said, “Open a vein and let it bleed all over the page.” My fiction writing is my attempt to stop someone else’s bleeding.

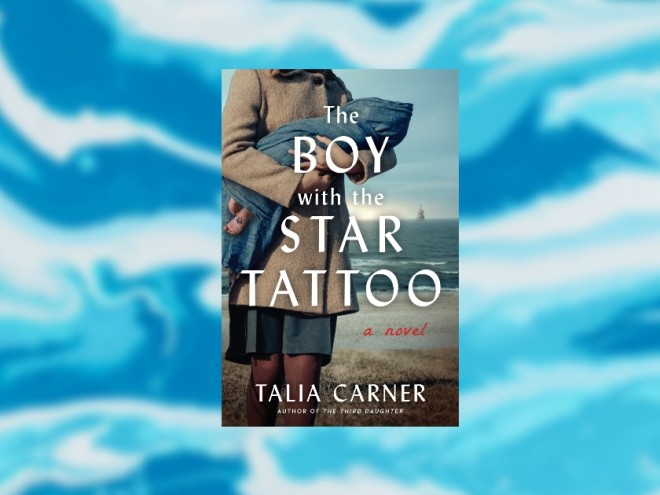

Novelist Talia Carner has authored six historical and psychological suspense novels that shed light on social indignities and unexplored historical events. Both The Boy With The Star Tattoo and The Third Daughter were named Finalists by the Jewish Book Council in the Book Club Categories. Formerly the publisher of Savvy Woman magazine and a lecturer at international women’s economic forums, Carner turned from trailblazing projects centered on women’s issues to fighting for Israel’s image. Born in Israel, she lives in New York and Florida.