blogs for The Postscript on one of his favorite paragraphs in his book and the importance of food.

To “host” Boris at your next book club meeting, request him through JBC Live Chat.

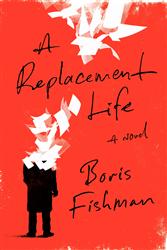

One of my favorite passages in my debut novel, A Replacement Life— the story of a failed young writer who starts forging Holocaust-restitution claims for old Russian Jews in Brooklyn who have suffered, “but not in the exact way[they] need to have suffered in order to qualify” — appears on page 20 and has no verbs oradjectives; there isn’t even a complete sentence in it. It’s a list. I reproduce it here, along withthe preceding paragraph for context. The young writer’s grandmother, a Holocaust survivor, hasjust passed away, and he makes his first return to south Brooklyn, where so many Russian-Americans live, in over a year — he has been trying to force his past out of his life — for herfuneral and commemoration. (The first names in the first paragraph refer to the home aides thatlooked after his grandmother when she was ill.)

One of my favorite passages in my debut novel, A Replacement Life— the story of a failed young writer who starts forging Holocaust-restitution claims for old Russian Jews in Brooklyn who have suffered, “but not in the exact way[they] need to have suffered in order to qualify” — appears on page 20 and has no verbs oradjectives; there isn’t even a complete sentence in it. It’s a list. I reproduce it here, along withthe preceding paragraph for context. The young writer’s grandmother, a Holocaust survivor, hasjust passed away, and he makes his first return to south Brooklyn, where so many Russian-Americans live, in over a year — he has been trying to force his past out of his life — for herfuneral and commemoration. (The first names in the first paragraph refer to the home aides thatlooked after his grandmother when she was ill.) I am often asked in what way I remain Russian more than a quarter of a century after myfamily left the Soviet Union, when I was nine. I feel no political kinship with the Soviet Union’sfallout republics (I was born in Belarus), and the one return visit I made, in 2000, excavatedpowerful sensory memories but left me with an equally powerful distaste for the lack of civility,paranoia, and xenophobia that continues to thrive there. So my answer tends to refer to theRussian literature that was my path back to my home culture after I’d spent a decade in Americatrying to forget it; the language, earthy and comic and supple and brusque; and the food. Is itbecause professional opportunity — not to mention other forms of personal expression, such asreligious identity — was so much more circumscribed in the Soviet Union that so much moreceremony and ritual significance was given to meals and community? All I can say is that to thisday, my family — its opportunities and self-expression circumscribed in America all the same,due to imperfect English, advanced age, and plain shyness — sits down to meals as to a greatrespite from the ordeals of the day. Great care is taken to prepare the meal, almost always athome, from scratch; it is pounced upon with an equally great hunger that sometimes feelsspiritual more than alimentary. The food is gone in a third of the time it took to prepare. It’s notthe French or Italian model.Slava used to sit at one of these tables once a week, the cooking by a Berta or a Marinaor a Tatiana, uniformly ambrosial, as if they all attended the same Soviet Culinary SchoolNo. 1. Stout women, preparing to grow outward even if they hadn’t reached thirty, intights decorated with polka dots or rainbow splotches, the breasts falling from their sailorshirts, their shirts studded with rhinestones, their shirts that said Gabbana & Dulce.

Stewed eggplant; chicken steaks in egg batter; marinated peppers with buckwheathoney; herring under potatoes, beets, carrots, and mayonnaise; bow-tie pasta withkasha, caramelized onions, and garlic; ponchiki with mixed-fruit preserves; pickledcabbage; pickled eggplant; meat in aspic; beet salad with garlic and mayonnaise; kidneybeans with walnuts; kharcho and solyanka; fried cauliflower; whitefish under stewedcarrots; salmon soup; kidney beans with the walnuts swapped out for caramelizedonions; sour cabbage with beef; pea soup with corn; vermicelli and fried onions.

Because food is so important both to the novel and its author — so much so that, havingfinished my second novel, out from HarperCollins next year, I am contemplating a Ukrainiancookbook as my third project — I invite you to make it a part of your book club discussion of AReplacement Life. Cross-pollination is welcome: One club, in Knoxville, TN, fortified itsdiscussion with vodka and lox. If there’s a Russian grocery store nearby, raid the shelves. And ifyou’re willing to try your own hand at a staple of the Russian table, I include a recipe for borshchfrom the woman whose cooking I want to highlight in the Ukrainian cookbook. I went down tosouth Brooklyn, where she looks after my grandfather, just last night, and made it together withher. You won’t regret the (not very taxing) effort. And in case it’s your discussion that needsfortification, I am also including a handful of discussion questions. Finally, I am available through the JBC Live Chat program to callor Skype into your book club if that would be of interest; you can reach me atcontact@borisfishman.com.

Because food is so important both to the novel and its author — so much so that, havingfinished my second novel, out from HarperCollins next year, I am contemplating a Ukrainiancookbook as my third project — I invite you to make it a part of your book club discussion of AReplacement Life. Cross-pollination is welcome: One club, in Knoxville, TN, fortified itsdiscussion with vodka and lox. If there’s a Russian grocery store nearby, raid the shelves. And ifyou’re willing to try your own hand at a staple of the Russian table, I include a recipe for borshchfrom the woman whose cooking I want to highlight in the Ukrainian cookbook. I went down tosouth Brooklyn, where she looks after my grandfather, just last night, and made it together withher. You won’t regret the (not very taxing) effort. And in case it’s your discussion that needsfortification, I am also including a handful of discussion questions. Finally, I am available through the JBC Live Chat program to callor Skype into your book club if that would be of interest; you can reach me atcontact@borisfishman.com.  The night before, boil three medium-size beets (anywhere from forty minutes to an hour andchange depending on their size and age). Leave the skin on and refrigerate. This helps the beetkeep its color and not blanch when it’s cooking the next day.

The night before, boil three medium-size beets (anywhere from forty minutes to an hour andchange depending on their size and age). Leave the skin on and refrigerate. This helps the beetkeep its color and not blanch when it’s cooking the next day. Boris Fishman was born in Minsk, Belarus. He is the author of the novels A Replacement Life (winner of the VCU Cabell First Novelist Award and the American Library Association’s Sophie Brody Medal) and Don’t Let My Baby Do Rodeo. Both were New York Times Notable Books of the Year. Savage Feast, a family memoir told through recipes, will be out in paperback in early 2020. His journalism has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, and many other publications. He lives in New York and teaches creative writing at Princeton University.