Havana, Cuba, 2010 Photo by Carol M. Highsmith, Library of Congress

In the early 1990s, about a decade after I started my professional career in art conservation, I decided to attend a preservation conference in Havana. This decision came out of nowhere. Though both my parents and I had been born in Cuba, my childhood had been fraught with stresses that were rooted in our Cuban past. My mother, for example, had grown up motherless and destitute in a Havana Jewish orphanage. My Jewish father was raised in a comfortable middle-class home by an immigrant businessman, but my paternal grandfather would not allow him to take some of their nest egg out of the country when Castro took power. This was a constant source of family arguments when I was growing up, especially because my father’s businesses in Miami were always going bankrupt. My adulthood had taken me first to Boston, then New York, then Philadelphia, and finally Los Angeles, far away from the nexus of the Cuban immigrant experience. And yet, an art conservator’s job requires us to seek and understand the source of damage as the prelude to repair. Somehow, I must have known this when I jumped at the chance to head to Havana.

The conference was sponsored by Cuba’s Centro Nacional de Conservacion Restauracion y Museologia (CENCREM). I was surprised by everything I saw. First and foremost, there was the breadth and depth of my Cuban professional counterparts’ abilities, even as the recent collapse of the Soviet Union had left them without resources like wax to line paintings, Japanese paper to mend drawings, and nearly every type of synthetic glue or solvent. Then there was the city itself, a nearly complete palimpsest of the last 500-years of architectural history in tile, bronze, limestone, terracotta, and marble. Most of Havana’s buildings were in disrepair, but still standing since no developers had an incentive to tear them down. How was it possible, I wondered, that the oddball profession I had chosen – art conservation – had so much to do with the place where I came from? And how could it be that no one in my family had told me that this legacy was as much a part of our past as the losses?

A few days into the conference, the deputy director of the CENCREM asked me if I would like to visit Havana’s Jewish cemetery. Luis Lapidus was a lanky and mustachioed architect a few years younger than my parents. Like my parents, he had been born in Cuba to Eastern European Jewish immigrants, but he had supported the revolution and decided to stay when most Jews left the country. I accepted his offer with enthusiasm.

United Hebrew Congregation Centro Macabeo Beyt Hayim is located in Guanabacoa, a hilly colonial town on the other side of Havana Harbor. As Lapidus drove me there in his Soviet-made Lada, he explained that Guanabacoa is a native Taino word that means “site of the waters.”

“Cuba’s original peoples were almost completely decimated by Spanish conquistadores,” he said, “but their presence is in all of our towns and places.” We entered past the cemetery’s tall gates, and Lapidus greeted an Afro-Cuban man who sat in the gatehouse. “Guanabacoa is also famous for the practice of Afro-Cuban religions,” he added, further explaining that practitioners of Santería, Palo Monte, and Abakua took care of the resting places of los muertos judios by removing weeds and gathering broken marble pieces. The man at the gate kept a large ledger that contained names cross-referenced to locations. This helped the many Jews who visited the cemetery from abroad locate their relatives among the many aisles of marble.

For conservators, repairing does not mean reversing. It means dealing with the fingerprints of history, incorporating what has happened into the story of the artwork.

All of those valiant efforts notwithstanding, the Jewish graveyard was in dire condition. Many lids were caving in from their own weight. Stars of David were missing points. Weeds sprouted through hairline cracks, and tombs were sugaring, a process that exfoliates small crystals of calcium carbonate. Inscriptions were so caked with fungus that many were hard to read. It looked like a textbook’s worth of marble damage.

Which was apparently the reason Lapidus had brought me here.

“How would you like to teach a workshop on marble restoration here?” he asked.

The idea seemed outlandish, but I felt my pulse race. Lapidus and I began discussing the logistics, how to get the adhesives and other repair materials to the island, when the course might be attempted. Even as we planned it, I envisioned my parents’ reaction. They already thought me crazy for returning to Cuba. For them the island was a bastion of irreparable losses, only worth visiting if it was possible to recover what had been usurped. But as I stood there, watching thunderheads roll towards us from the north, I realized that there was more to recover than simple possessions. For conservators, repairing does not mean reversing. It means dealing with the fingerprints of history, incorporating what has happened into the story of the artwork.

Just then, lightning flashed over the ocean to the north. Lapidus said, “Would you like to find any of your relatives here? If so, we should hurry up and do it.”

We made our way back to the gatekeeper. I gave him a list of names, beginning with my maternal grandmother, Rosa Oxman, the woman who had died from complications of giving birth to my mother. He flipped the pages of his large book and shook his head. But he had the locations of Chaya Felman, my mother’s grandmother, and Fanny Lowinger, my father’s aunt.

Lapidus led me first to my great-grandmother’s grave. I placed a stone on the marble and said the kaddish. “Amen,” responded Lapidus.

The thunder rumbled closer, so we hurried in the direction of my father’s aunt’s grave. As I rushed to follow Lapidus, the tip of my sandal caught the broken sidewalk. I fell onto a tomb. It was badly eroded. But the name was clearly visible:

Rosa Oxman Felman.

That afternoon, the grandmother I am named for, the woman whose tragic death set off a chain of devastating consequences that framed my entire life, reached out to remind me that my interest in repair — the reason I became a conservator — is rooted in the story of our family’s damage. It originated there, with her in Cuba. Conservation is founded on the idea that things of value are worth retaining, and that our paths in life are often marked by error. A tiny roadblock or a broken piece of concrete can make all the difference. Our cracks and fissures are what authenticate us.

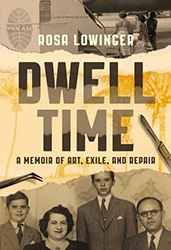

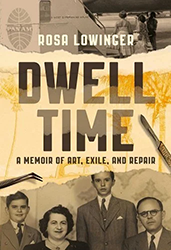

Dwell Time: A Memoir of Art, Exile, and Repair by Rosa Lowinger

Rosa Lowinger is a Cuban-born American writer and art conservator. The author of Tropicana Nights: The Life and Times of the Legendary Cuban Nightclub (Harcourt, 2005) and Promising Paradise: Cuban Allure American Seduction (Wolfsonian Museum, 2016), she is the founder and current vice-president of RLA Conservation, LLC, one of the U.S.’s largest woman-owned art and architectural conservation firms. A Fellow of the American Institute for Conservation, the Association for Preservation Technology, and the American Academy in Rome, Rosa writes regularly for popular and academic media about conservation, historic preservation, the visual arts, and Cuba.