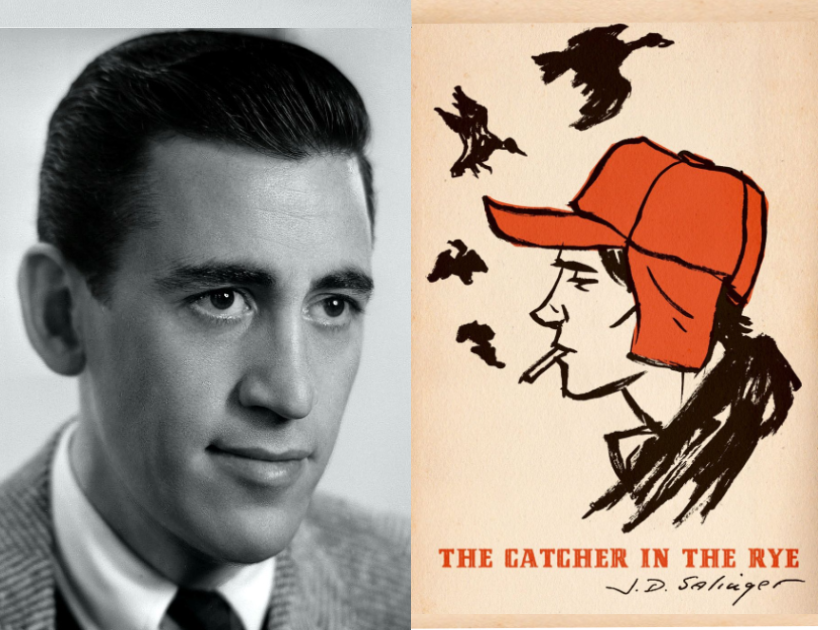

J. D. Salinger photo by Lotte Jacobi, used in the first edition of The Catcher in the Rye

J. D. Salinger, the most reclusive writer of the twentieth century, remains an enigma. He retreated to Cornish, New Hampshire, at thirty and spent most of his time in a bunker behind his country house. He stopped publishing fiction by the time he was forty-five, but may have another forty-five years of writing — stories, a spy novel, memoirs, countless tales of Seymour Glass— squirreled away inside a safe in his bunker when he died in 2010. There have been promises that the remains of his oeuvre would be issued to us at regular intervals, but so far we haven’t witnessed a single word of this hidden treasure. We know he practiced a kind of Vedanta Hinduism, populated with migrating souls like the characters in his books. Supposedly he drank his own urine. He was unkind to his first two wives, and disinherited his daughter. But what do we really know about him?

His father, Solomon or Sol, was the son of a rabbi who became a medical doctor. His mother, an Irish Catholic, pretended to be Jewish to please Sol, and changed her name from Marie to Miriam. Salinger had an older sister, Doris, who would become a fashion buyer at Bloomingdale’s. Sonny, as Salinger was called, grew up on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, opposite the Museum of Natural History, in a predominantly Jewish neighborhood. He attended Camp Wigwam, a summer playground for affluent Jewish children, and was the star of his own little acting troupe at the age of ten. He even went through the ritual of a bar mitzvah, which I describe in Sergeant Salinger.

______

The bar mitzvah was a kind of showpiece, staged for Sol’s parents, Simon and Fannie Salinger, who had come all the way from Chicago, where Simon was a medical doctor with his own private practice in a neighborhood of the poorest Jews in the world on Chicago’s South Side — Simon had financed his medical studies by serving as a rabbi in Louisville, a town of goyim with its tiny ghetto. He was a hard man not to notice. His left eye had been torn out of its socket in a pogrom. It happened in 1880, while Simon was a member of the volunteer Jewish police in the Lithuanian town of Taurage; scuffling with the czar’s drunken soldiers outside the central synagogue, he was gouged with a bayonet. No one had to pity him. Simon gave much more than he got. He left two of the czar’s louts lying with smashed skulls on the clay road. A renegade now, on the czar’s death list, he had to run to America. But that gouged eye intrigued Sonny. Simon didn’t cover it with a velveteen patch. His empty socket looked like a sinister tunnel with a flap of skin …

Sol had hired an itinerant rabbi with a Torah in a silver case to please his father and mother, but Simon disapproved of this charlatan, and he knew that Sonny recited from the Torah without understanding a single line. Yet he loved the boy, felt a kinship with him. He could sense that zeal in Sonny’s dark eyes, the boy’s search for God. Grandpa Simon hadn’t lost his predilection for mayhem. He took the itinerant rabbi with his Torah and tossed him out of the apartment, and then he had a shouting war with Sol in one of the back bedrooms, while Sonny spied on them, like a secret agent wrapped in a prayer shawl.

Sol had hired an itinerant rabbi with a Torah in a silver case to please his father and mother, but Simon disapproved of this charlatan, and he knew that Sonny recited from the Torah without understanding a single line.

“You had no right, Pa.”

“Faker,” Simon cackled. “I had every right in the world. I would break your bones if it weren’t for the boy. You never taught him the Haftarah. He doesn’t even know about the Prophets.”

“I did teach him — I tried. And I found the best rebbe I could.”

And that’s when Grandpa Simon discovered Sonny in the crack of the door. He had tears of anger and frustration in his eyes. He’d been a battler all his life. But he couldn’t slap Sol’s big ears back in front of Sonny. He welcomed the bar mitzvah boy into the room.

“It’s nothing,” he said. “Pay no attention. I never got along with your father. He loved to swindle, and I never could.”

He wiped his eyes with a handkerchief that was as long as a dish towel and walked Sonny out of the room …” [1]

______

Sonny saw himself as a kind of King David, a religious singer with his own lyre. But he soon had a fall from grace. His family uprooted itself and moved across town to 1133 Park Avenue a few months after Sonny’s bar mitzvah. And while they were all having dinner at Schrafft’s one evening, Sol, who was the vice president of a company that produced unkosher ham and cheese, announced that the Salingers weren’t Jewish, and that Miriam wasn’t Miriam at all, but an Irish Catholic from Iowa. It shook Sonny, who lost his lyre and his religious roots in a simple matter of fact announcement at Schrafft’s.

I’m not quite sure Sonny ever recovered. He converted to Catholicism for a while. He went through the horrors of World War II — includingthe landing at D‑Day, the liberation of a death camp, acting as a member of the Counter Intelligence Corps, and spending two weeks at a mental hospital in Nuremberg after the Nazi war machine collapsed. His experiences are captured with crisp detail in Salinger’s masterful short story, “For Esmé — with Love and Squalor,” where Sonny appears as Sergeant X, who has suffered a complete mental collapse.

No wonder he became a recluse and sent all his characters on oddly spiritual quests. None can find much peace in this world. All of them, including Holden Caulfield and members of the multi-talented Glass family, suffer from Salinger’s angst;they practice a kind of Upper West Side Buddhism, or what the late Steven Marcus called “Jewish Zen.” Salinger’s strengths as a writer come from the constant chatter he picked up on the streets — he’s a bar mitzvah boy gone amuck, the poet laureate of Camp Wigwam, wounded by war.

[1] [Sergeant Salinger, p. 269 – 271] Excerpted from Sergeant Salinger. Copyright © 2021 by Jerome Charyn. Published by Bellevue Literary Press: www.blpress.org. Reprinted by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Jerome Charyn is the author of more than fifty works of fiction and nonfiction, including Ravage & Son; Sergeant Salinger; Cesare: A Novel of War-Torn Berlin; In the Shadow of King Saul: Essays on Silence and Song; Jerzy: A Novel; and A Loaded Gun: Emily Dickinson for the 21st Century. Among other honors, his work has been longlisted for the PEN Award for Biography, shortlisted for the Phi Beta Kappa Christian Gauss Award, and selected as a finalist for the Firecracker Award and PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction. Charyn has also been named a Commander of Arts and Letters by the French Minister of Culture and received a Guggenheim Fellowship and the Rosenthal Family Foundation Award for Fiction from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He lives in New York.