Some people find Christ in their darkest hour. Others turn to Allah. But if you’re a Jew, young, and in trouble, your best bet is Leonard Cohen.

I was thirteen when I accepted the singer as my personal savior. I grew up in a beachside suburb of Tel Aviv, Israel, the spoiled child of a wealthy family. One afternoon, I came home from school, tossed my backpack on the floor, and raided the fridge in search of lunch when someone knocked on the door. It was the police. Three detectives politely forced their way in and informed me that my father — the jovial bon vivant whose hobbies included fast cars, fine hotels, and fat foods — had just been arrested. He was caught red-handed, the lead detective told me matter-of-factly, and confessed to being the Motorcycle Bandit, a brazen criminal who had hit up more than 20 banks in just a few months and whose antics made him a folk hero to many.

And, just like that, life as I knew it ended. I was no longer the child of privilege; I was now the son of the most notorious criminal in a country too small to keep secrets or award privacy. Our house filled up with visitors, and I remember my mother commenting bitterly that it felt like a shiva, the traditional Jewish mourning ritual in which friends and relatives gather to keep the bereaved company.

If the adults had appropriate words of condolence at their disposal, the adolescents, my friends, did not. Like teenaged boys everywhere, they had received no training in the art of empathy, and did not know how to console one of their own in the face of such strange trauma. Instead of words, then, they did what teenaged boys everywhere do and offered mixtapes.

Most of these were dross, catchy pop concoctions that went down easy and left no lasting impression. But one stood out. It contained an assortment of songs by Leonard Cohen.

I barely spoke English then, but Cohen’s words pierced right through the language barrier. They didn’t peddle in sentiment. They weren’t thick with bravado. They spoke a difficult but liberating truth. When I listened to “The Sisters of Mercy” for the first time, for example, I shuddered at the line about those “who must leave everything that you cannot control / It begins with your family, but soon it comes down to your soul.” It didn’t feel like a song lyric; it felt like an insight plucked from some higher realm, telling me to persevere, suggesting that things were tough but not hopeless. Alone in my bedroom, after all the well-wishers had left, I played the tape over and over again. It was the only thing that gave me comfort.

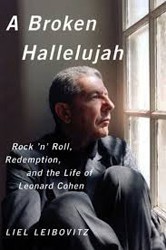

It took me twenty years of growing up and another four of listening intently to Cohen’s music for a book I was writing about him to understand just what I had found so reassuring as a wounded youth. Other artists were better at capturing raw emotion, at stirring the bloodstream, at washing you over with happiness. But then you took off your headphones and walked back out into the world, and the thin mist of feelgood soon evaporated. Like over-the-counter medicine, music was way too weak to fight back the symptoms of life in such an imperfect world. To cure true afflictions, you needed something stronger.

How strong? Consider the following lines, from Cohen’s song “Anthem”: “Ring the bells that still can ring / Forget your perfect offering / There’s a crack in everything / That’s how the light gets in.” We’ve no better distilled version, perhaps, of Cohen’s ideas than this, and no greater proof that what the baritoned bard is offering isn’t just entertainment but theology. A scion of several renowned rabbis, he believes, like the Jewish sages of old, that redemption is funny business: the messiah, goes the old Jewish adage, will only come when all Jews are kind and pious, but when all Jews are pious and kind, they would no longer need the messiah. There’s enormous wisdom in this cosmic joke. It tells us not to wait for someone else to swoop in and save us. It says, sadly, that we’ve no right to expect divine grace, and that the only thing we have, the only thing we need, is ourselves: with enough hard work, and a little bit of love, we all could transcend even the darkest of fates.

That’s the spirit that animates Cohen’s greatest songs. It’s also the spirit that saved me. After my father’s arrest, religious relatives suggested I partake in their practices, but I found little inspiring in the certainties of religious orthodoxy. Cohen showed me another way to worship, one that understood that because we humans are so imperfect, every hallelujah we mutter comes out broken but is no less holy or joyous for it. It’s not an easy idea to comprehend. It’s not immediately appealing like “all you need is love” or “give peace a chance.” But it has made Cohen, at eighty, the closest thing we have to a prophet, and it had made me, at thirteen, find the strength to carry on.

Liel Leibovitz is the editor at large for Tablet Magazine and the host of several of its popular podcasts, including Unorthodox and Take One. He’s the author of several works of non-fiction, and a frequent contributor to publications like The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and others. A Ninth-Generation Israeli, he now lives in New York with his family.