I was 28 before I first saw the Statue of Liberty in person. I’d been accepted to grad school in New York City, and my husband (then fiancé) and I flew out together to see the school — and, in my case, to see the city for the first time. It was a hasty trip, with a red-eye flight and a hodgepodge itinerary. We had friends of friends in Chelsea, and they graciously allowed us to crash at their place. It turned out they lived on one of the busiest corners in the city, and the incessant cab-honking kept us awake most of the night. It was a very New York welcome.

I was 28 before I first saw the Statue of Liberty in person. I’d been accepted to grad school in New York City, and my husband (then fiancé) and I flew out together to see the school — and, in my case, to see the city for the first time. It was a hasty trip, with a red-eye flight and a hodgepodge itinerary. We had friends of friends in Chelsea, and they graciously allowed us to crash at their place. It turned out they lived on one of the busiest corners in the city, and the incessant cab-honking kept us awake most of the night. It was a very New York welcome.

That first afternoon, still fuzzy with jet lag, we took a walk out to the Hudson Park greenway. At Chelsea Piers we stopped to watch the trapeze students swinging through the air above us, looking nervous in their leotards and safety harnesses. We walked out to the end of one of the piers, and that’s where I caught my first real-life glimpse of her.

Wow, I thought. Here I am. There she is.

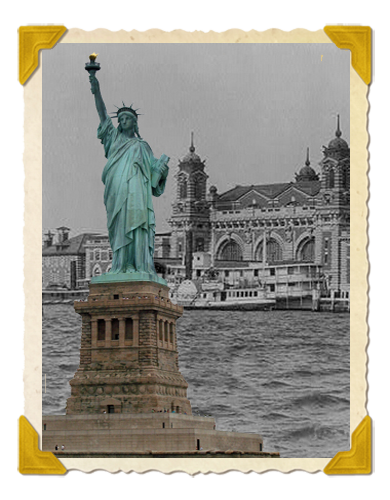

At that distance she was just a slim gray silhouette, motionless on her pedestal. Tour boats churned at her feet; helicopters swooped past her like dragonflies. She seemed like the only still object in a moving world. Looking at her, I felt what I’d later come recognize as a particularly New York-style cognitive dissonance: the weird fact of this huge, iconic thing just sitting there, minding her own business, while the city went about its afternoon.

A few years after I stood on Chelsea Pier, I gave a character in The Golem and the Jinni the traditional immigrant arrival in America: a steamship cruising past the statue, the waving hands and the tears of joy. Except that my character is far from a traditional immigrant. She’s a golem, newly created and alone. She has no knowledge or understanding of the statue; she doesn’t even know what liberty is — though she’s newly liberated herself, her master having just died. But she recognizes that the people around her love the statue, and she takes comfort in the fact that it is clearly a constructed woman, like herself.

If you think about it, the Statue of Liberty is an oddity among monuments. We Americans like our statues to be of real people, of presidents and heroes and civic leaders. But the Statue of Liberty is a personification, a portrait of an idea, and a female one to boot. (Name one other woman whose face is so closely associated with the idea of America.) She’s become such an everyday image that it’s hard to remember that The Statue of Liberty isn’t just her name, but her function, the purpose for which she was built. A Statue, representing Liberty. And as it turns out, Bartholdi and his workers were merely her first set of creators. In the years that followed she was brought to life again and again, a multitude of animations, as each immigrant en route to Ellis Island filled her with a new set of hopes and fears, longings and disappointments. In that sense, she’s the ultimate American golem.

Read more about Helene Wecker here.

Related: Emma Lazarus

The Golem and the Jinni was awarded the Mythopoeic Award, the VCU Cabell Award, and the Harald U. Ribalow Prize, and was nominated for a Nebula and World Fantasy Awards. Her work has appeared in Joyland, Catamaran, and in the anthology The Djinn Falls in Love and Other Stories. She lives in the San Francisco Bay area with her family.