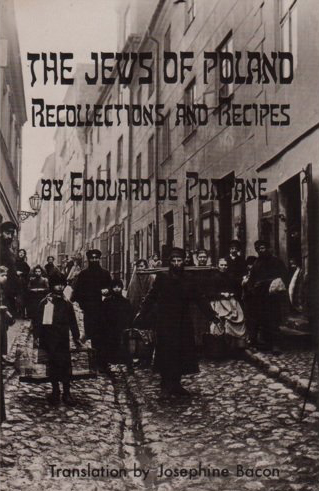

When I was researching my last novel, my friend Michael Rohatyn found a book at the Strand he thought I might like: The Jews of Poland: Recollections and Recipes, by Edouard de Pomiane. De Pomiane (1875−1964), a physician, was also one of the most famous chefs and cookery writers of his day. Born Eduard Pozerski, he was born into the Polish aristocracy, brought up poor but refined. Both his parents were Polish patriots who fought against Russian domination of their homeland; his mother fled to France with the young Eduard when his father was deported to Siberia for insurrection against the Russians. Coming of age within the close-knit community of Polish exiles in Paris, he was sympathetic to liberal causes and was a proponent of the Dreyfus cause.

When I was researching my last novel, my friend Michael Rohatyn found a book at the Strand he thought I might like: The Jews of Poland: Recollections and Recipes, by Edouard de Pomiane. De Pomiane (1875−1964), a physician, was also one of the most famous chefs and cookery writers of his day. Born Eduard Pozerski, he was born into the Polish aristocracy, brought up poor but refined. Both his parents were Polish patriots who fought against Russian domination of their homeland; his mother fled to France with the young Eduard when his father was deported to Siberia for insurrection against the Russians. Coming of age within the close-knit community of Polish exiles in Paris, he was sympathetic to liberal causes and was a proponent of the Dreyfus cause.

His ethnographic book about Polish Jewish culture and cooking, written in 1928, was originally entitled Cuisine Juive; Ghetto Modernes (Jewish Cooking; Modern Ghettos). It is, perhaps, the weirdest book I have ever read. A tantalizingly vague recipe for Carpe a la Juive (“Take a large, live carp. Kill it…”) follows a horrifying description of a pogrom, relayed to de Pomiane by a museum guide who had survived the massacre by hiding under a heap of hay in which his sister suffocated overnight: “A corpse, belly ripped open, lay with its guts wrapped around its neck…A child wandered aimlessly, haggard, mute, crazed, its body beaten to a pulp.”

In de Pomiane’s writing, appreciative paragraphs about the accomplishment of certain refined Jews rubs shoulders with unwittingly racist pseudo-science. “I observed as a biologist…wrote as a scientist,” claims de Pomiane, as he cheerfully divides all male Jews into three types:

1. “The dark-haired Jew, with a long beard and a delicate, aquiline nose. His lips are often thin, his ears lie flat against his head. His eyes are deep, almost mystical. He is less excitable than the others. It could be said that he belongs to an ethnic aristocracy. He has an Egyptian profile.”

2. “This type is also dark-haired, and much more common. His beard is black, shorter, his eyes are bulging and bloodshot, his nose is squat, his lips are thick and very red, and he enormous, flat eats. This is the excitable Jewish type. When he laughs, he sniggers. The face, overall, has a cruel and bestial appearance. Certainly this type of Jew would frighten a child in France, even if that child were himself Jewish.”

3. “A third, and rarer, type is completely red-headed. The beard is shorter and divided in two. He has the same negroid facial charactersitics as the preceeding type. The lips look even thicker and frame the teeth with two red borders of eaqual sixe. Although they are red, the peissy look brown from being rolled, twisted, and curled between fingers that are constantly being licked.”

Having provided us with this helpful diagram of Jewish types, he takes us on a tour of Jewish Poland, beginning with Kazimierz, the Jewish Ghetto in Crakow since the Middle Ages:

“The whole place seems fairly, and in some places, extremely, poverty-stricken. The more so since the population is dirty and strange. In Kazimierz, everyone dresses in black, everyone rushes about in a hurry, they all bustle about irritably, pushing, shouting, arguing. One would think the whole city were in the grip of some nervous disease.”

De Pomiane believes that these poor, nervous Jews give us a sense of what the tribes of Israel must have been like, “these people who when settled among us became the educated and refined individuals with whom we are familiar.” So, De Pomiane argues, the less “Jew‑y” the Jews are, the more European, the more refined they are — and hence, it seems, equal to non-Jews. Unfortunately in only a few years there was no refinement that could save a Jew in Poland, or indeed, France: being Jewish was considered a racial fact, not a cultural subtlety. But de Pomiane’s distinctions are fascinating because they are being spouted by a man who was actually sympathetic to Jewish culture.

De Pomiane’s observations are strikingly detailed. Describing the typical kaftan, he states, “they wear a long black cloth gown which descends to their feet. It is not waisted like an overcoat, but is slightly fuller. Two rows of buttons secure it over the chest. This kaftan is quite high-necked.”

And then, he describes a head-covering that can be found in contemporary Williamsburg: “Older Jews wear black hats of brushed felt. These head-coverings are worn very far forward, a little over the eyes, because on the crown of the head, under the hat, they wear a little black scull-cap.”

He speaks of prostitution: “Just as in the Orient, one sees in the streets of Cracow and Warsaw, Jews attempting to draw in the passerby to admire a supposed daughter or niece.”

And the book is not short of anecdotes: a friend of de Pomiane’s was tempted by an old man who spoke of a girl “as beautiful and fresh as a mountain stream.” Tantalized, he followed the old man into an ancient house and through a rather dark and very smelly courtyard. “The Jew opened a door; my friend entered a room which was quite clean and saw a young girl in profile.” She was a perfect beauty. Then she turned to face him and he saw that one of her eyes had been gouged out. When he left in a panic, the old man cried, “It wasn’t for an eye that you followed me here!”

De Pomiane takes us to a stylish health resort called Zakopane. There, de Pomiane finds a lot of rich Jews. “What is so surprising?” he asks. “They alone…engage in trade. They alone are rich, and they alone can afford to vacation in Zakopane.”

Spending time with these wealthy, assimilated Jews, Pomiane is amazed at their patriotism. A doctor he met “defended both Zakopane and the whole of Poland…he was a proud Polish nationalist. There are men like these among Jewish intellectuals who have achieved a certain status in life… having left the kaftan and the ghetto behind…they have almost forgotten Yiddish, replacing it with very good German. They call themselves Polish.”

De Pomiane the ethnographer paints a fascinating portrait of a class divide amongst the assimilated versus the unassimilated Jews:

“Try and imagine a Jew in his worn, shiny, discolored kaftan, with his beard and side-locks on his temples. Imagine him strolling down the Avenue Henri-Martin in Paris, which is inhabited almost exclusively by wealthy French Jews. Would he be welcomed as a compatriot by those elegant ladies getting out of their automobiles, whose children speak English to their nannies? Definitely not. These “Israelites” [a term favored at the time by assimilated Jews as more politically correct than ‘Jew’] avoid the Polish Jew, whom they have dubbed ‘Polak’.”

The book encapsulates contradictions and subtleties within the Polish Jewish population between the wars, but also within the writer himself, a Polish Francophile exile who loved food and had an abiding interest in Jewish cuisine. Beef Bouillon with Sauerkraut, Chicken Soup with Almonds, Goose Soup with Barley, Carp a la Juive — these recipes and many more are all lovingly preserved for the curious gourmand in this most curious of books.

Read more about Jacob’s Folly and Rebecca Miller here.