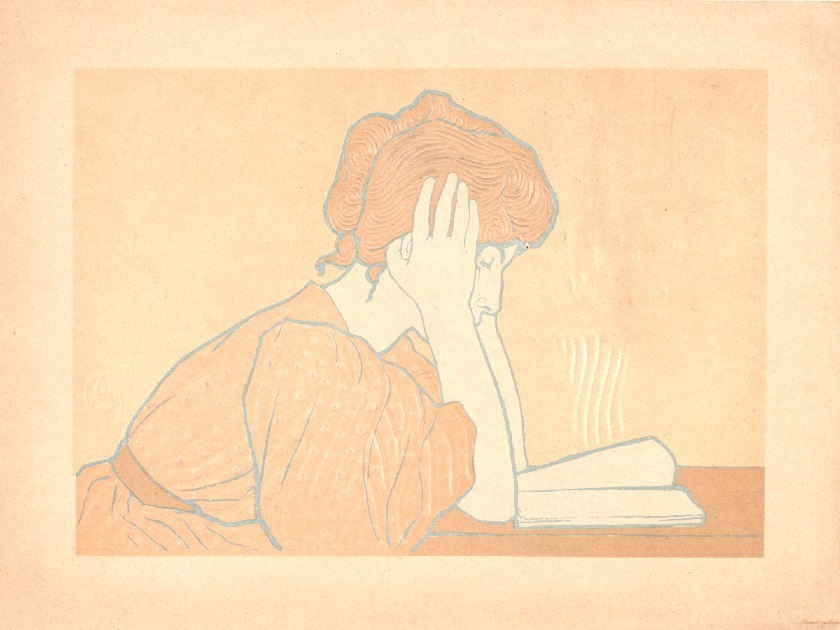

Young Woman Reading, Alexandre-Louis-Marie Charpentier, 1896

The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Purchase, Clifford A. Furst Bequest, by exchange, 1992

In an article for The Paris Review entitled “Writing the Lives of Forgotten Women,” Rachel Kadish notes: “What the historical record has rendered invisible will remain so unless we avail ourselves of the power to fictionalize, to blend the real and the imagined with rigor and transparency.” As more contemporary female novelists portray silenced women of the past, they add a new dimension to our understanding of previous eras.

Throughout history, women were often denied the time and space to create — except when creating children. Virginia Woolf famously explored this topic in her 1925 work A Room of One’s Own, but the issue was certainly not limited to her time. More than half a century later, the American Jewish author Hettie Jones wrote an account of the disparity between male and female literary production in her 1990 memoir, How I Became Hettie Jones, illuminating how difficult it was for her, as a new mother, to find opportunities to write, and how such opportunities were never denied her writer and activist husband, Amiri Baraka (previously known as LeRoi Jones):

“At the northern tip of East River Park there’s an overgrown quarter acre with some benches facing the water and a neglected, sinking monument.… I was there one day, sitting apart from the children in order to pay attention to myself, impossible in their immediate presence: if they demanded they also seduced, like the TV that captures because it’s on. We’d left Roi at home, typing in his windowless box of a room. When I’d looked in to say goodbye he was grinning [about a book he was going to write]. Yesterday evening while I was bathing Kellie, he’d come dashing into the bathroom with a poem. ‘Look at this! Read this!’ he cried.” It took Jones ten years to write her first book, whereas her husband published at a clip throughout their marriage and the birth of their two children.

Another Jewish author, Tillie Olsen, wrote the article “Silences: When Writers Don’t Write” in Harper’s magazine (1965), which she later expanded into a book of the same name. “More than in any human rela tionship, overwhelmingly more,” she states, “motherhood means being instantly interruptible, responsive, responsible.… Work interrupted, deferred, postponed, makes blockage — at best, lesser accomplishment” (as quoted in The Portable Sixties Reader edited by Anne Charters).

Have Jewish female writers struggled differently, or more, compared to female writers in general? While it was historically rare for any woman to be published, non-Jewish female writers (such as Edith Wharton, or the Brontë sisters) succeeded more often than Jewish ones. Jewish culture values scholarship — an attitude embodied in study of the Talmud — but this pursuit was traditionally reserved for men. In America’s Jewish Women: A History from Colonial Times to Today, Pamela S. Nadell explains that according to biblical law, ancient Israelites were commanded: “Thou shalt teach them diligently unto thy children” but she reminds us that “across the ages, that meant educating males, not females. Boys growing into men spent lifetimes in study. Girls learned to read and write enough to run a home and a business.… If they yearned for more, there were fewer opportunities.” While the men studied, wrote, and dreamed, the women toiled to keep the family afloat, financially as well as domestically. In her autobiography, The Promised Land (published in 1910), Mary Antin writes: “There was nothing in what the boys did in heder that I could not have done — if I had not been a girl.… A girl’s real schoolroom was her mother’s kitchen … And while her hands were busy, her mother instructed her in the laws regulating a pious Jewish household and in the conduct proper for a Jewish wife.… A girl was born for no other purpose.”

Ironically, the first impetus to educate Jewish girls in Eastern Europe, aside from the influence of Enlightenment ideals, was so that when they became mothers, they could better instruct their male children. In an article published in the Russian-language periodical Rassvet in 1860, educating Jewish girls is clearly presented as a means to an end: “In Jewish society the mother of the family has an even bigger influence on the children than in Christian families. The head of the family, given all his concerns, spends almost all of his time outside of the house, leaving the children and their instruction to the mother; and therefore, so that this instruction will go correctly, it is necessary to think seriously about the education of Jewish women” (as quoted in Jewish Women in Eastern Europe edited by ChaeRan Freeze, Paula Hyman, and Anthony Polonsky).

As more women write their stories and the stories of others, thankless labor is being replaced by productive, creative work.

This attitude toward Jewish women was carried over from the Eastern European shtetl to America. In Sara Berman’s Closet, Maira Kalman and her son, Alex Kalman, commemorate the life of their mother/grandmother, who was born in Russia, immigrated to Israel, and eventually made a home for herself in New York. In an interview on NPR, Maira Kalman describes Jewish women’s work in her mother’s childhood Russian village as “silent toil;” they were so busy churning, cooking, and cleaning that they didn’t have time for conversation. At some point, a woman might sit down and enjoy a glass of tea, and then perhaps one could have a chat, but to attempt to create, to write — that was entirely out of the question. Nadell demonstrates that a woman’s aspirations were limited in much the same way in the United States. Professionally, it “was fine for girls to work as bookkeepers, stenographers, and secretaries before marriage, and smart ones were expected to play dumb to catch a husband.… A Jewish woman might work after she wed, especially if she was putting her husband through professional school. But those days ended when she became a mother.”

The prospect of a Jewish woman entering into a professional or creative field was bleak — particularly if the woman wanted to write. But as Jews assimilated into American culture, and left behind some of the more rigid cultural traditions from the Old Country, a few Jewish women began to venture into the literary sphere, such as Mary Antin, Anna Margolin, and Anzia Yezierska. The scope of these writers was relatively narrow and based mostly on personal experience, perhaps because they lacked the time or resources to research beyond that experience, or perhaps because they did not feel entitled to write about what they did not know — to assume authority and ownership over voices other than their own. By contrast, male writers have always exerted this kind of authorial control and power. In the beginning of the twentieth century, while Antin and Margolin wrote about their families who immigrated to America from Eastern Europe, and the challenges of assimilation that they faced in the new world, Sherwood Anderson, for example, encompassed the broad canvas of a rural community in Winesburg, Ohio (1919).

Today — perhaps due in part to financial progress and increased time for one’s own pursuits, as well as changed attitudes toward Jews and women in publishing — female Jewish authors are constructing multigenerational, multiperspective novels of ambitious length and geographic sweep, recreating various places and eras with historical accuracy and vividness. These authors bring to life the experiences of “silent toilers,” who, until now, were erased from our consciousness. In Rachel Kadish’s 2017 novel, The Weight of Ink, a seventeenth-century Jewish woman, Ester Velasquez, secretly chronicles the dispersal of Jews from Inquisition-era Spain to Amsterdam and London. When a trove of Ester’s papers is discovered in the present day, scholars are stunned that they were written by a woman. In “Writing the Lives of Forgotten Women,” Kadish explains that in part what motivated her to write this novel was that, aside from the female writers we already know about who masked their identities with male pen names in order to be published, there must have been countless “other artists of erasure: women scattered here and there across cultures and centuries who expunged themselves from the record so the work of their hands and minds and hearts could be visible. And if they were good at it — if they succeeded — we’ve never heard of them.”

Sana Krasikov’s The Patriots is also a sprawling, multigenerational novel, and it is written in part from the point of view of Florence Fein, another unlikely protagonist who embodies an untold story of past Jewish women. It’s the classic immigrant narrative told in reverse, contrasting with earlier works that idealize the American Dream (such as Antin’s The Promised Land, in which even hardship and suffering acquire a golden sheen). Krasikov reveals a little-known aspect of history: the migration of American Jews back to Russia in the 1930s. She also defies narrational and historical expectations of how Jewish women, particularly Jewish mothers, are portrayed in fiction. Florence boldly rejects the idea that family must come first. When she decides to go to Russia, leaving her parents and brothers behind in Brooklyn, her father cries out: “What kind of madness is this, for a girl to want to leave her family, her home, all the people who love her? To the other end of the world!” Later in the novel, Florence abandons her son in a Russian orphanage when he is six and does not retrieve him until he is thirteen. Krasikov captures the pain of this experience from the son’s point of view: “We were hit for anything — for throwing up the rotten food we were fed, for whistling indoors, for forgetting ourselves and sucking our thumbs — for displaying any childlike frailty or need.” For Florence, political action is more important than her young son’s welfare.

Stylistically, Krasikov employs traditional realism and an omniscient narrator, displaying a type of maximalism that recalls the work of male writers of previous eras, such as Joseph Roth’s The Radetzky March (1932) or Isaac Bashevis Singer’s The Family Moskat (1950). But the story she tells is quite different. Krasikov fluidly moves from Florence’s point of view to that of Florence’s first love interest, Sergey; to Florence’s son and to her grandson; before circling back to Florence’s most intimate thoughts. Sergey’s point of view opens up another pocket of unfamiliar history: the position in which upper-middle-class Russians found themselves after the Revolution — not proletarian enough but not truly aristocratic, either. Sergey’s experience of post-revolutionary Russia diverges greatly from Florence’s idealized version of the country; the omniscient narrator allows the reader to perceive the disconnect inherent in the arcs of these two characters’ stories. This trend might seem to run counter to other current literary movements, such as #OwnVoices, which value authors writing from their own lived experiences. But in fact, it springs from the same impulse: to reclaim narrative power and authority. As Cynthia Ozick argues in The Paris Review’s “The Art of Fiction,” No. 95, the essence of fiction is imagining and creating other subjectivities, other lives and worlds. “The self is limiting.… When you write about what you don’t know, this means you begin to think about the world at large. You begin to think beyond the home-thoughts. You enter dream and imagination.”

The heart of the creative process is about reaching across generations, cultures, and genders to convey an emotional truth, whether lived or imagined.

Rosellen Brown’s The Lake on Fire is another recent novel that reclaims the past both narratively and linguistically. The book centers around the World’s Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893, and Brown comments in a Jewish Book Council interview that its prose reflects that of the Gilded Age: “[The Lake on Fire] has long, intricate sentences, unlike my other books.… I really tried to write the book in a style compatible with the time I was writing about.” Like The Patriots, the book relates a piece of Jewish history unfamiliar to most modern-day readers: the lives of Jews in the nineteenth-century Midwest. Brown’s protagonist, Chaya, leaves the family farm in rural Wisconsin, the Fields of Zion, for another kind of life. On the novel’s first page, Brown depicts the life Chaya will ultimately reject, in a detailed description of her mother: “The children’s mother was brusque to them all, so busy they remembered her mainly in motion — sewing, darning, cooking, planting, sweeping — all the -ing words, her hands flashing faster than barn swallows. There wasn’t much left of her for loving, although they knew that the motion was somehow meant for them.” Just as Krasikov’s Florence refuses to concede to traditional expectations, so too does Chaya abandon the silent toil she has been raised to do. Her final push for independence comes when she realizes she’s about to be married off to the nephew of a family friend: “And then he winked at her. One of those pale reptilian eyes creased in a coy flicker of greeting, as if she had agreed to something, and she could feel her hands becoming fists in her lap. Suddenly, then — it made so much sense that she gasped out loud — finally, finally, she understood that she had been waiting for this: She was going to leave the Fields of Zion.”

But when Chaya starts over in Chicago to make her fortune, with her little brother in tow, she ends up laboring tirelessly at a cigar factory and living in poverty. Brown reveals the truth behind the American Dream — that hard work and pulling oneself up by one’s bootstraps are rarely enough to survive, let alone create social mobility. This is also foreshadowed earlier, when Chaya is still with her family on the farm and she reflects on their life: “They tilled and planted and harvested after hours and how could they not have broken under the burden of their double work lives? So much optimism undone. So much energy wasted.” Neither the city nor the country carries any promise for the poor. Just as Krasikov’s Florence is unable to fulfill her communist ideals in Russia, so too the American Dream remains forever out of the reach of Brown’s protagonist.

These novels give us a second chance to imagine the lives of silent toilers — from the young scribe, to the rebellious immigrant, to the farm girl who tries to outrun her fate. They break the grand narrative of history into various overlapping and contradictory narratives that embrace all the messiness and variety of the human experience. As more women write their stories and the stories of others, thankless labor is being replaced by productive, creative work.

The troubling question persists as to why novels by women set in another time period are often categorized as “historical fiction,” when novels by men in the same style and historical vein — such as McEwan’s Atonement— are perceived by critics and publishers as “literary fiction”? This difference in reception still threatens to undermine the perceived seriousness of women’s contributions to literature. The heart of the creative process transcends marketing campaigns and genre classifications — it’s about reaching across generations, cultures, and genders to convey an emotional truth, whether lived or imagined. Recognizing this may be our next challenge.

Alexis Landau is a graduate of Vassar College and received an MFA from Emerson College and a PhD in English Literature and Creative Writing from the University of Southern California. She is the author of The Empire of the Senses and lives with her husband and two children in Los Angeles.