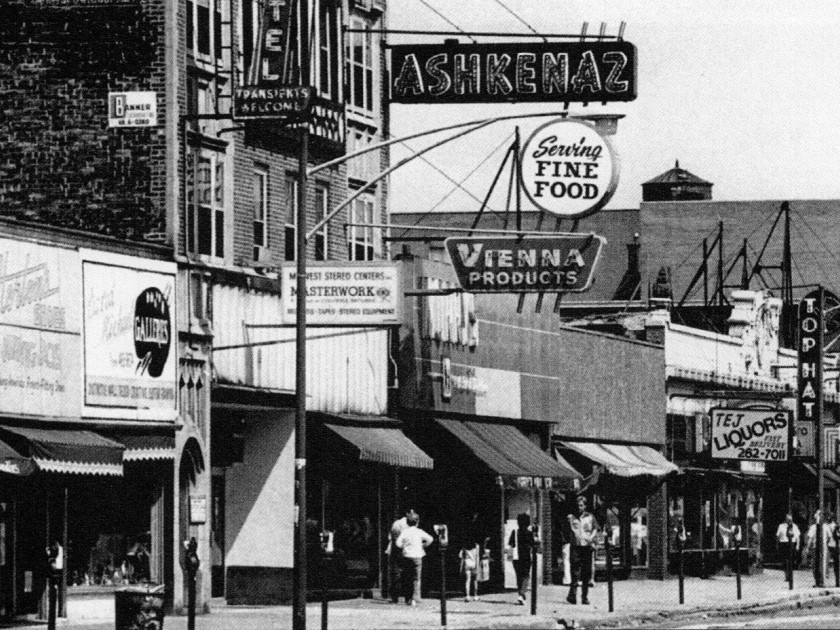

Ashkenaz Deli, from the Digital Research Library of Illinois History (drloihjournal.blogspot.com)

When I was ten years old my parents would often take me and my brothers and sister to Ashkenaz Delicatessen in Chicago. It was quite a place, famous for its corned beef, fried kreplach, and fresh blueberry blintzes, a landmark for authentic Jewish food that dated back to 1910, when Russian immigrants George and Ada Ashkenaz first opened their doors to the Jews living in and around Chicago’s Gold Coast neighborhood.

What I remember most about the deli is the powerful aromas that wrapped around you like a warm blanket when you stepped in the door: garlic, corned beef, pastrami, chopped liver, and dill pickles. I always ordered a humongous corned beef and chopped liver sandwich. What a delight it was trying to finish it. My dad had a plate of the fried kreplach; my mother had the matzah ball soup. She would offer each of us a bite. The matzah ball was as warm as her smile.

The Ashkenaz Deli seemed to provide comfort and protection against an unpredictable world. Sitting among the clattering of dishes and the familiar rhythms of the boisterous, accented conversations, the deli gave our family a point of connection. For my brothers and sister, my mom and dad and grandparents — good Jewish food was something we all enjoyed. We would argue sports and politics as we devoured the delicacies on our plates.

There was always a crush of customers fighting to get into line next to the glowing meat counter. It was quite a sight watching old Jewish ladies elbowing their way to the counter to place their orders, each with her own strategy to cut in front of the line. Of course, each one of them had a loaf of Jewish rye tucked under her arm when she left.

The three or four counter men kept up a constant stream of chatter as they sliced corned beef, pastrami, and salami, their voices loud above the hum of the meat slicer. One of the men behind the counter was the owner. His bald head glistened in the fluorescent lights, and his thick black frame glasses made his eyes huge as he monitored every movement in his deli. Like a flash he would scurry to a table to urge the busboys to move faster so he could seat the customers forming a line at the door.

There were three old men who always sat at a small table in the back. I couldn’t take my eyes off of them. They appeared as three characters out of an Isaac. Bashevis. Singer story. While we waited in line to occupy the next available table, I studied their every movement. They were always lost in conversation, and they rarely looked up. They were impervious to the clatter. Sometimes I could hear snippets of their animated exchanges. Once I heard them discuss their now defunct shul, and I learned that one of the men was a rabbi, the other a retired cantor. The third old man remained a mystery. In the winter, all three were wrapped in heavy coats. Once in a while they would pepper their discussion with Yiddish words, which I didn’t understand. With each new bit of information I gathered I became more and more intrigued. One of the men was a real kvetch. His complaints were usually accentuated with quick, nervous hand gestures. He complained about anything: the weather, the slow service, the noisy crowd. The other two men, obviously used to their friend’s constant grousing, ignored it. It was funny to watch them.

I have thought about these old men for the last sixty years. I didn’t want to let go of them. I made them part of my family. Why did they have such an impact on me, a ten-year-old boy? I don’t know. Over the years, my memory of them has faded. Their faces have vanished, the sound of their voices has grown weaker and less distinct. I grew worried that these three old men would disappear entirely, that their stories and their lives would be lost. I wrote a story called “Who’s the Old Crone?” in order to call them back into existence, as vivid and colorful as they were sixty years ago, even if they now live only on the page. I hope the memory of the deli and the three old men stays alive in the heart of anyone who reads “Who’s the Old Crone?” Is my retelling of their story accurate? Well, it’s my story, and I am sticking to it!

What follows is an excerpt showing how I reimagined the three old men of the Ashkenaz Deli, circa 1960:

And what a group they were: Rabbi Fiddleman, an intense and precise man who was prone to fits of irascibility, with impish, sparkling eyes and perfectly formed ears that seemed a gift from the Almighty himself. Unfortunately, as sometimes happens in this life, when the Powers That Be decide to have a laugh at our expense, someone pays a dear price. In this case, it was the rabbi who was the butt of the heavenly joke — Fiddleman’s ears were all show, only the left one retained any acuity, which forced him to cock his head awkwardly to the right and thrust his left ear forward to hear a word anyone said. Many of his former congregants surmised that this difficult and taxing maneuver accounted for the rabbi’s periodic crankiness. Rabbi Fiddleman was a scholar of the old school; he was exacting in his application of Jewish law but rendered his opinions with a just and kind heart. Thus, his judgments, as well as his advice, which he dispensed liberally, were accepted by his followers without grumbling. The rabbi always wore a silk kippah atop his closely cropped gray hair and tzitzit under his dusty jacket and held court each day in Schwartzman’s with his two followers — Pincus Eisenberg and Mendel Nachman.

Eisenberg, Rabbi Fiddleman’s loyal sexton for over fifty years, could always be found at Fiddleman’s left shoulder. This gave Eisenberg unfettered access to the rabbi’s best, only half-deaf ear, which he filled with a continuous series of complaints. Pinkus was nicknamed the Kvetch, a moniker he earned when he was just a toddler in Brasov, Romania. The then colicky Pinkus, named after his father’s father according to tradition, was descended from a long and distinguished line of rabbinical scholars and, considered a child prodigy by his doting parents, was expected to surpass the accomplishments of his erudite predecessors. One morning, the toddler Pinkus, still at his mother’s breast at a year and a half, was observing the world from his cradle and exhibiting early, telltale signs of his lifelong cynicism — a furrowed brow and piercing stare. It was from this cradle that Pinkus uttered his first words. As the story goes, Pinkus, on that cold, dreary morning, was holding his ample belly and groaning from his crib, making every effort to persuade his frazzled mother to come and feed him. But, distracted by her many household duties, she took longer than usual to respond to the increasingly hungry and impatient Pinkus. Finally, her hands free, the harried mother approached with loving, outstretched arms to gather up the now apoplectic child. Pinkus furrowed his brow, puckered his pudgy lips, and moaned his very first words to his astonished and proud mother, “Oy vey … what took so long?” And the Kvetch was born.

For the next eighty plus years, complaints rolled off his tongue: “There’s not enough onion in my chopped liver,” he would wail at Schwartzman as he devoured great quantities of the special recipe. “What, no heat … it’s so cold,” he would sniffle to anyone close at hand as he shivered in his seat with his fedora pulled down to his ears, his overcoat collar turned up, and his gold-rimmed pince-nez perched on the tip of his red, dripping nose.“The borscht … not enough cream,” he would belch after gulping prodigious quantities of the chilled soup, and so on. It was said the brainy Eisenberg could kvetch fluently in seven languages. That the rabbi still befriended the touchy sexton and endured with a stiff upper lip Eisenberg’s grousing over the many years was testimony to Rabbi Fiddleman’s patience, his unbending faith in a Supreme Power, and, most importantly, his ever-increasing deafness.

The third, and no less colorful, member of the breakfast club was Mendel Nachman. A notably small man, Nachman had a long, prestigious career as cantor at the Romanian synagogue. Because of his powerful and perfectly pitched voice, at one time Nachman was mentioned in the same breath as the great Yossele Rosenblatt. “How can such a small man have such a powerful voice?” everyone asked after hearing the diminutive Nachman sing. “Such a big voice coming from such a small man is proof the Almighty graced Nachman with a special blessing,” was the obvious answer.

On festivals and holidays, Jews from every part of the city packed into every available corner of the shul to hear the master and sat transfixed as they listened with tightly closed eyes, absorbing the rich baritone coming from the resplendent Nachman. His powerful voice would spill into the street, and anyone who happened by was drawn into the overcrowded synagogue to see for themselves who brought forth such music. As he sang, Nachman’s face glowed like a Sabbath candle. Women in particular singled out the bachelor Nachman for effusive praise and listened to his songs with nothing short of rapture.

But now Nachman’s light was extinguished, and he sat depressed each morning in Schwartzman’s, rarely uttering a sound. The master of song had become mute. What happened to the cantor?

Nachman’s gradual decline began almost two years before the synagogue was closed. After fifty years of professional singing, he began to struggle to hit the high notes, notes that before he had found with ease. At first, Nachman shrugged it off and attributed his difficulty to the onset of a cold. “After all, didn’t the Festival of Lights arrive at a time of the year when everyone was coughing and sneezing?” he reassured himself while sipping gallons of hot tea, gargling glass after glass of salt water, and wrapping his neck with warm towels to soothe his throat. The hope that his problem was temporary, that it would be only a matter of time, just a few days really, before he would be at his best once again, gave Nachman some comfort. But then, much to his horror, he found that he struggled to hold notes. His breathing, once controlled and deep, the source of his powerful sound, now felt erratic and shallow. His once richly layered voice was shrill and thin as parchment. This decline left him despondent. The cantor’s confidence melted away like ice in spring.

Over the next several months, things for Nachman went from bad to worse. As his voice diminished week by week, Nachman became more and more desperate. He spent his days in his small, richly furnished apartment pacing with worry and practicing for hours. But no matter the amount of practice, he continued his steady decline. Then, one day, Miss Hepenheimer, the dried-up old bitty who lived two doors down, rapped on his door. The old lady, with a bony, masculine face and a low, coarse voice to match, immediately lit into Nachman, brandishing two knitting needles and snarling about the “off-key warbling” that grated on her nerves, making the short time she had left in this life a living hell. Nachman, too stunned to respond, stood mute in the doorway holding his teacup, his throat swathed in warm towels, until the old woman wearied and, after one last menacing shake of a knitting needle, took her leave.

“Everyone’s a critic,” he muttered to himself.

Craig Darch is the Humana-Sherman-Germany Distinguished Professor of Special Education at Auburn University. He is author of From Brooklyn to the Olympics: The Hall of Fame Career of Auburn University Track Coach Mel Rosen.

How I Got Interested in Writing the Mel Rosen Biography

My Parents’ Legacy, My Library, and the Mel Rosen Biography