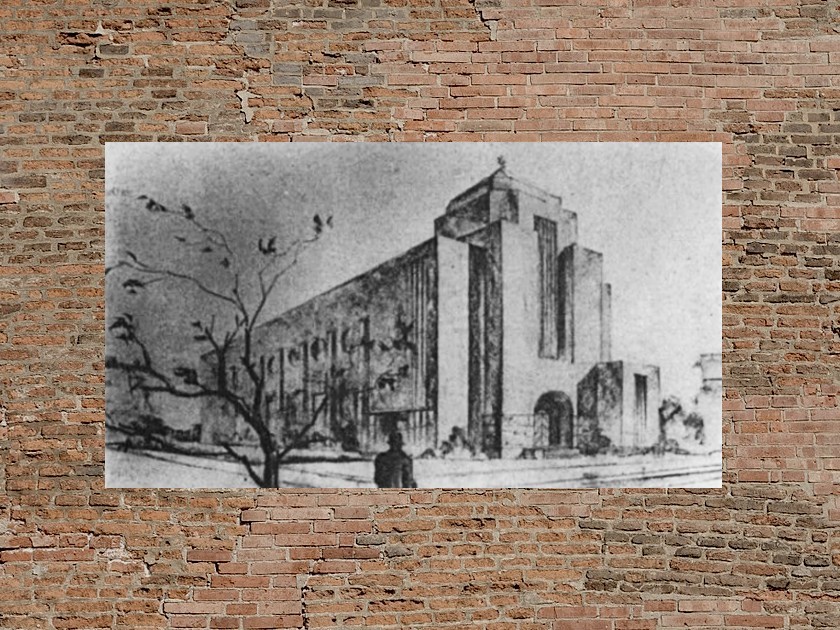

Sketch of the proposed New Synagogue, Shanghai, 1937

Helmi’s Shadow traces the life of my mother, a stateless Russian Jew named Helmi Koskin; Helmi was born in 1923 in Japan to her Russian mother, Rachel Cooper (my grandmother), and a Finnish father, Edward Koskin. My grandmother had been born in Odessa, located in the Pale of Settlement, but grew up in the northern Chinese city of Harbin, which had a substantial population of Russian Jews in the early twentieth century. Helmi’s father died in Japan when she was very young, and Rachel returned to China around 1925; here she raised Helmi under difficult circumstances in Shanghai until 1939. At this point they both returned to Japan, where they remained throughout World War II. They managed to survive bombings by the Japanese in Shanghai and by the Americans in Japan. After the war ended, they found a way to come to the United States, where they each finally attained citizenship for the first time in their lives. My mother married a man from Reno, Nevada, named William Horgan and raised a family there. She and my grandmother lived in Reno for the rest of their lives.

Growing up in Reno, I heard stories from both Helmi and Rachel about their early lives, so distant from my own, but there was a great deal I didn’t understand. I interviewed my mother more extensively late in her life and was able to put together more of the story, but still much was unclear. I likewise tried to persuade my grandmother as she aged to divulge more of the past, with mixed success. It was only after both of their deaths that I undertook more rigorous research to fill in the missing information. I tracked down relatives and friends who had known Helmi and Rachel in both China and Japan. I read extensively about the Asian cities where they had lived – Harbin and Shanghai, in China, and Kobe, in Japan – which harbored communities of Jews from Russia, as well as from various European countries, during the decades of horrendous conflict in the twentieth century.

Helmi’s Shadow is divided into two halves. The first part traces the years from my grandmother’s birth in Odessa, her escape from antisemitic Russian pogroms with her family to China, the years of hardship in Shanghai, and then the war years in Japan. The second part focuses on the subsequent decades in America – told mostly through my own eyes – as my brother and I grew up under the wings of these remarkable women. We perceived our mother as a widely admired and exotic figure in Reno with a mysterious past, and our grandmother as both a tragic and comical little old Russian lady. There was a great deal more to be learned about both of them.

Delving into our family histories is far more than a mere academic exercise. Keeping such stories alive is, I believe, a vital task as well as a deeply felt labor of love.

I made many wonderful discoveries that greatly aided and enhanced my research. A number of historians have, in recent decades, delved deeply into the histories of Jewish diaspora communities in Asia during the previous century. Two excellent examples are To The Harbin Station by David Wolff and Port of Last Resort: the Diaspora Communities of Shanghai by Marcia Reynders Ristaino. These books, and others, enabled me to more fully understand how and why displaced people like my mother and grandmother lived and survived under such difficult circumstances. I also came to understand much more clearly how displaced Jews of various nationalities in Russia and East and Southeast Asia managed to create their own tight communities and help protect each other during times of tremendous violence and danger. My book includes an extensive bibliography of other useful sources.

I also made use of a number of personal memoirs by other Jews who experienced life in these places and fraught times. One of the most important such books, and most valuable to me, is titled Somehow We’ll Survive, by George Sidline – a memoir of his time as a young Jewish boy in Kobe, Japan, during the harrowing years of World War II. As I began to read George’s book, suddenly I came to a chapter where he began to talk about my own mother and grandmother, who were close friends of his parents. From his memoir I learned a great deal about their personal lives as well as many details about how they survived the war years in Japan among a tiny group of other Jewish families, with very little food and having to dodge the tremendously destructive American bombings. I subsequently located George Sidline and visited him and his wife Simonne in their home, where they provided me with more information and wonderful photographs. Sadly George passed away recently, and he will be greatly missed.

Delving into our family histories is far more than a mere academic exercise. Keeping such stories alive is, I believe, a vital task as well as a deeply felt labor of love.

David Horgan is a writer and professional musician. His book of short stories titled The Golden West Trio Plus One received the Merriam-Frontier Award from the University of Montana. His stories and essays have appeared in a number of publications, including The New Montana Story, The Best of the West, Portland Review, Quarterly West, Northern Lights, and The Crescent Review. Born and raised in Reno, Nevada, he now lives in Missoula, Montana.