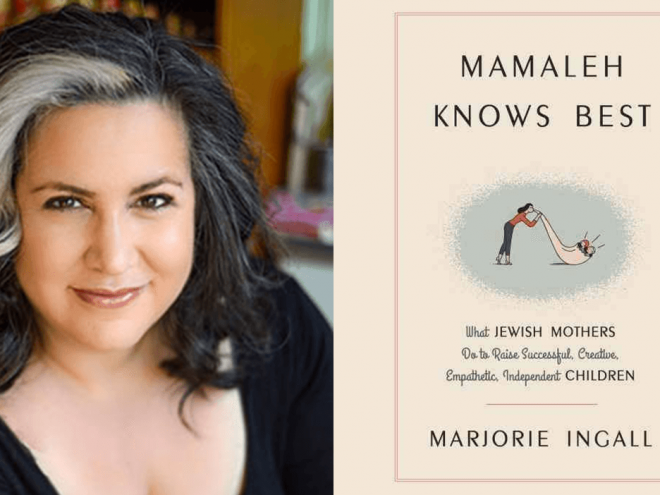

Earlier this week, Marjorie Ingall wrote about stepping out of ghostwriting to write her first book since 1998. With the publication of that book, Mamaleh Knows Best: What Jewish Mothers Do to Raise Successful, Creative, Empathetic, Independent Children, Marjorie is guest blogging for Jewish Book Council all week as part of the Visiting Scribe series here on the The ProsenPeople.

1. I did a metric ton of research. When I was in college, I dealt with my fear of writing papers by exfoliating. Through an excellent and protracted skin-care regimen, followed by the ritual cleaning of the dorm room and doing laundry until 4:00 AM, I worked myself into enough of a last-minute panic that I could actually sit down to write. This is not a great strategy for a 47-year-old woman. So I dealt with my anxiety by doing more and more and more research. I was convinced that once I knew everything in the entire world about everything in the entire world, the book would flow out of me like sweetened condensed milk out of a dorm fridge after my roommate’s stash tipped over.

2. I was terrified of writing in my own voice. As a ghostwriter, I found the very notion confusing. How scholarly should I be? How much of my funny blogger (www.sorrywatch.com) voice should I use and how much of my journalism voice?

Who the hell was I? Since I could not decide, my first draft was both late and terrible. My best friend, a novelist, told me I sounded unable to own my authority. She pointed out that I kept defaulting to other people’s words to drive my own points home. I quoted big wads of academic texts. I sourced everything multiple times. I sounded pretentious, uncomfortable and stilted. “You can be self-deprecating while still sounding confident and erudite,” she told me gently. It took a long time for me to relax into that advice. Perhaps paradoxically, I had to learn to sound like myself.

Who the hell was I? Since I could not decide, my first draft was both late and terrible. My best friend, a novelist, told me I sounded unable to own my authority. She pointed out that I kept defaulting to other people’s words to drive my own points home. I quoted big wads of academic texts. I sourced everything multiple times. I sounded pretentious, uncomfortable and stilted. “You can be self-deprecating while still sounding confident and erudite,” she told me gently. It took a long time for me to relax into that advice. Perhaps paradoxically, I had to learn to sound like myself.

3. Deadlines! When you’re writing a book, deadlines are fake! Sure, you can put arbitrary due dates for each chapter in your calendar, but when you’re writing articles that have to be filed every week, or magazine stories that have to come in on time or no one will ever hire you again, you know that book deadlines are stretchy and fungible. Also, book payments come in very slowly. Payments for one’s regular gigs come in more quickly. One deludes oneself about what one should be doing at any given moment.

Also one needs to check Facebook and Twitter constantly.

4. The state of publishing. I went through three editors and two publicists (at last count) over the course of working on Mamaleh Knows Best. Chaotic times, changing industry. My first editor was a Member of the Tribe with a small child, and her editorial questions seemed targeted to readers like her. My second editor was the parent to much older children and was not herself Jewish; her primary interest seemed to me to be broadening the book’s readership. Finally, I was accustomed to writing celebrity books, which are not, shall we say, heavily edited. So I was surprised to get detailed, passionate editorial notes on each chapter. The part of me that came of age writing for women’s magazines was a people-pleaser and wanted to do everything the editors suggested; the part of me that had a specific vision for the book (a blend of social history, folklore and mythology, humor, theology and parenting, high culture and pop culture) wanted to push back. It was uncomfortable. My second editor was frustrated by my harping on Philip Roth; I knew I wasn’t doing a great job explaining why his work was essential to understanding the weight of the Jewish mother stereotype, but I couldn’t accomplish what I wanted to. (My editor was also horrified that I desperately wanted to keep a  paragraph about Portnoy’s foodstuff-related masturbatory habits, comparing them to the pastry penetration in American Pie. “Why is this here?” she kept demanding. “This will turn off your reader completely!” Ultimately, I decided that a discussion of Jewish men ejaculating into comestibles was not the hill I wished to die on. In the end, there is perhaps less Philip Roth in my book than there should be, but fewer people will gag while reading it, so I’ve got that going for me, which is nice.) Ultimately, editing made this book much, much better. And shorter: I cut 20,000 words from the second draft. Everyone says “editors don’t edit anymore,” but this was not my experience, and no lie, I’m glad.

paragraph about Portnoy’s foodstuff-related masturbatory habits, comparing them to the pastry penetration in American Pie. “Why is this here?” she kept demanding. “This will turn off your reader completely!” Ultimately, I decided that a discussion of Jewish men ejaculating into comestibles was not the hill I wished to die on. In the end, there is perhaps less Philip Roth in my book than there should be, but fewer people will gag while reading it, so I’ve got that going for me, which is nice.) Ultimately, editing made this book much, much better. And shorter: I cut 20,000 words from the second draft. Everyone says “editors don’t edit anymore,” but this was not my experience, and no lie, I’m glad.

5. Who is this book for? How Jewish should it be? How much knowledge should I assume the reader has? Am I talking about Jewish parenting now, or Jewish parenting in different eras of history, and what the hell is the difference? As I wrote and revised, I felt I was tap-dancing like crazy to reach readers of many different backgrounds. (My favorite review so far is by a popular, very critical Goodreads reviewer who is not Jewish and has no children— the fact that she enjoyed it will make me feel good to my dying day, ptui ptui ptui.) The wrestling act made the writing act take much longer than I’d expected. And I’m sure the book will frustrate yeshiva-bred readers for whom not enough material is brand new, as well as goyish readers who feel it is too dang Jewish. Here, for example, is a story that was left on the cutting room floor because explaining Purim to the uninitiated made it take too long to get to the punchline:

Back when my daughter Josie was four, she was playing Queen Esther with my mom. Josie liked to dress in a tulle skirt, sunglasses, and multiple strands of Mardi Gras beads and plastic leis; then she’d line up her stuffed animals on the couch and sit primly at one end of the line with her hands folded. Whichever family member she’d force to play Ahasuerus had to go down the line and interview each stuffed animal about why it deserved to be his queen. My mom would always try to keep the process from focusing purely on looks — even though that’s what the actual text does — because she wanted Josie to think about qualities more important than physical appearance. Mom would play an Ahasuerus looking for qualities like kindness, generosity, patience. Anyway, once Mom asked Josie, “So, Esther, what qualifies you to be my queen?” Josie looked at her like she was a moron and said, “I have the skirt.”

Back when my daughter Josie was four, she was playing Queen Esther with my mom. Josie liked to dress in a tulle skirt, sunglasses, and multiple strands of Mardi Gras beads and plastic leis; then she’d line up her stuffed animals on the couch and sit primly at one end of the line with her hands folded. Whichever family member she’d force to play Ahasuerus had to go down the line and interview each stuffed animal about why it deserved to be his queen. My mom would always try to keep the process from focusing purely on looks — even though that’s what the actual text does — because she wanted Josie to think about qualities more important than physical appearance. Mom would play an Ahasuerus looking for qualities like kindness, generosity, patience. Anyway, once Mom asked Josie, “So, Esther, what qualifies you to be my queen?” Josie looked at her like she was a moron and said, “I have the skirt.”

Marjorie Ingall is a columnist for Tablet Magazine and a frequent contributor to The New York Times Book Review. She has written for many other magazines and newspapers, including The Forward (where she was The East Village Mamele), Real Simple, Ms., Food & Wine, Glamour, Self, and the late, lamented Sassy, where she was the senior writer and books editor.

Related Content:

Marjorie Ingall is the author of Mamaleh Knows Best: What Jewish Mothers Do to Raise Creative, Empathetic, Independent Children, and The Field Guide to North American Males. A former columnist for Tablet and the Forward, she is a frequent contributor to The New York Times Book Review and has written for a gazillion other outlets.