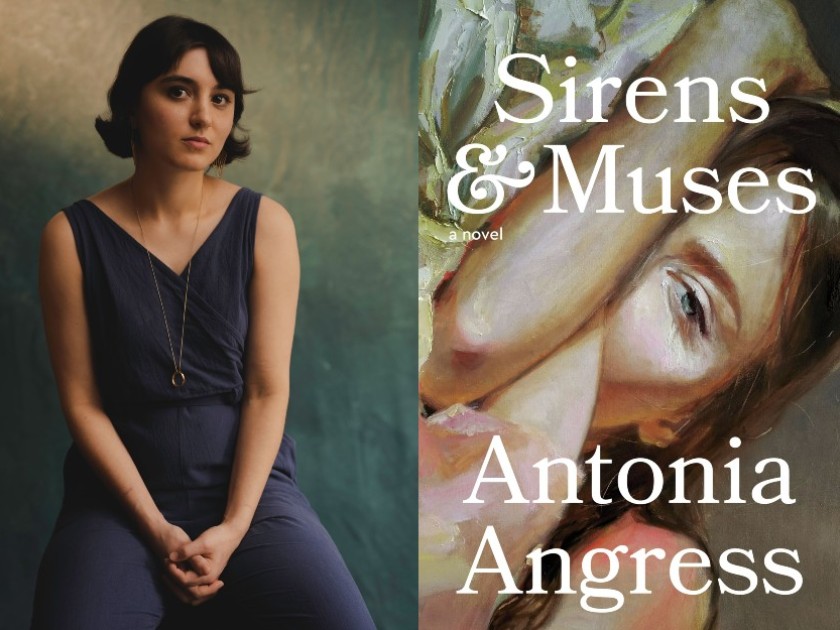

Author photo by Dena Denny

“Art is power,” observes one of the four protagonists of Antonia Angress’s debut novel, Sirens and Muses. At Wrynn College of Art in 2011, creative achievement dominates all aspects of life. Louisa Arceneaux, a wide-eyed transfer student, is drawn to her wealthy, aloof, and talented roommate, Karina Piontek. The college’s artist-in-residence, Robert Berger, struggles to make paintings that feel meaningful in the digital age, while Preston Utley — Karina’s brash sometimes-boyfriend — seems poised to gain ever more popularity with his blog, The Wart.

In conversation with Becca Kantor, Angress discusses the ways in which Sirens and Muses subverts assumptions about the artistic process; the Jewish history that underpins the novel’s themes; and how, despite being “not a particularly visual thinker,” she has crafted a book as vivid as her characters’ best work.

Becca Kantor: A few months ago, you made a wonderful post for JBC’s Instagram about Still Alive, an internationally bestselling memoir by your own grandmother, Ruth Klüger, who was a Holocaust survivor. I’d love to begin there. How did your grandmother’s experiences or work influence you as a writer?

Antonia Angress: My grandmother loomed large in my life, always. I don’t really remember a time when I was not aware of the Holocaust and her experience of it. My grandmother was born in Vienna and lived there until the Anschluss. She was deported when she was about nine or ten, lived in a ghetto for a while, and then was transported to a camp, ultimately ending up in Auschwitz. So she spent most of her adolescence in the camps.

I also always knew my grandmother was a writer, and I became interested in writing when I was quite young. I remember her teaching me to write a limerick when I was seven or eight. She was incredibly encouraging of me. She would buy me books. She was one of the first people who told me, “You’re a really good writer. You should keep doing this.” When I was ten or eleven, she bought me my first computer. I grew up abroad in Costa Rica, and my grandmother lived mostly in California, spending some of her time in Germany. So I saw her maybe once a year. But throughout my entire childhood and up until my early thirties when she passed away, we had a relationship conducted largely by email.

I first read her book when I was thirteen, which in retrospect might have been too young. But by then I was familiar with the broad contours of her story. I knew she’d gone through horrible things. I knew she’d almost starved. I knew she had numbers tattooed on her arm. What struck me when I read the book was what a phenomenal thinker she was. And how funny, too. She had a dry sense of humor, and the way it comes through in her book sometimes surprises people.

BK: Before I read your book, I didn’t anticipate that it might have Jewish content until I came across an interview you gave for Electric Literature. In it, you say: “I think home, to me, is more people than it is a place. Added to that my family is Jewish, and my grandparents were Holocaust refugees. Jews are notorious, historically, for being this stateless, rootless people — this ethnic group that’s always having to flee and is never able to put down roots.”

I’m curious as to whether that legacy of migration also influences the Jewish characters in Sirens and Muses. In particular, does it affect their impetus for making or collecting art?

AA: My work in general is preoccupied with belonging and home, and what it means to live in a place, put down roots in a place, or leave a place. That certainly has its origins in my own family’s history of expulsion and migration, and also in my own experience growing up in a country where my parents were foreigners but where I largely could pass as local unless I told people that I wasn’t. I felt like I existed between worlds. Even though I’ve lived in the US my entire adult life, there are still ways in which I feel like an outsider, still things that bring up flickers of culture shock.

In Sirens and Muses, that theme actually shows up most explicitly in one of the non-Jewish characters, Louisa. She is Cajun, part of another ethnic group that experienced expulsion and persecution. She’s the character who is most concerned with what it means to belong to a place and to a landscape. But in terms of the two Jewish characters: Robert is the son of Holocaust refugees. This is mentioned almost in passing — there were earlier drafts of the novel in which it was a much more significant part of the narrative arc, but I ended up paring it down. And then there’s Karina. This is something not a lot of people pick up on, but Karina’s half Jewish.

BK: Yes! I was so intrigued by the casual mention of her bat mitzvah money. And we learn that Karina’s father, who is an art collector, will sometimes spot paintings that his family used to own before the Holocaust in museums.

If I could pull Karina out of the book and ask her, I don’t think she would identify first and foremost as Jewish. But there is a sense in which the Holocaust lurks in her background, in the texture of her upbringing.

AA: His grandparents were also art collectors and they lost their collection to the Nazis. Yes. If I could pull Karina out of the book and ask her, I don’t think she would identify first and foremost as Jewish. But there is a sense in which the Holocaust lurks in her background, in the texture of her upbringing. Which is how it was for me. There was an ambient sense of loss, which I didn’t dwell on all the time — I didn’t wake up every morning thinking about the Holocaust — but was an inextricable part of who I was and how my family came to be.

BK: Did you set out to include that specific type of Jewish representation in your book? Or did Karina’s Jewish identity come about organically, as a reflection of how you see American Jews living their lives today?

AA: Part of it was that. Both of my parents are Jewish, but my cousins, for example, are only Jewish on their dad’s side, and they don’t identify as Jewish as far as I know. It’s certainly a part of their family history, and it’s not something that they deny or are ashamed of in any way. But it’s not a central part of their identity. I think that’s true of a lot of people I’ve encountered over the course of my life within the Jewish Diaspora.

Until I went to college, I did not know many Jews outside my immediate family because I grew up in a very Catholic country. I think I identified strongly as Jewish because it was something that made me different from most of the people there. But there was also a way in which I felt like an imposter, especially when I got to college. For the first time in my life, there were tons of Jewish people around me, and they all had had a different experience of being Jewish. I grew up in a Jewish household, but a secular Jewish household. They’d gone to Hebrew school and had bar and bat mitzvahs. Their knowledge of Judaism was not as piecemeal as mine. And there were ways in which I felt like, Oh, I am not Jewish enough?

Karina was always half Jewish to me. That’s how she emerged in my mind. And I knew from the beginning that Robert would be the son of Jewish refugees. I pulled that directly from my dad’s story. I knew I wanted to have a couple of Jewish characters in Sirens and Muses because it felt weird to me as a Jewish writer to write a book in which Jewish characters are entirely absent.

BK: Turning to another aspect of Karina’s life: soon after her friendship with Louisa becomes romantic, she claims that “Any painter can seduce their model, History is full of artists banging their muses.” Louisa is taken aback — she sees the power dynamic between them quite differently, partly because they are both women. How would you define a muse? How does Karina and Louisa’s relationship subvert what we might think of as the classic artist – muse relationship?

AA: In the popular imagination, the muse is a passive figure. She — and I feel like the muse is almost always a she—provides the inspiration. She’s literally an object, the object of the artist’s gaze. Certainly when I was younger, I saw the muse as a figure who is twisted into a reflection of the artist’s own desires and ideas, and then is discarded. There’s a John Berger quote I love: “Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” I think this is ingrained in how we think of the artist – muse relationship. We have this prescribed narrative of what this heterosexual dynamic between the artist and the muse is supposed to look like. Because culture has bombarded us with depictions of it. History is full of examples of it. If you’re in a heterosexual artist – muse relationship, it’s easy to fall into a role that’s already been written for you.

If you’re in a heterosexual artist – muse relationship, it’s easy to fall into a role that’s already been written for you.

One of the things that I wanted to do with the relationship between Louisa and Karina was to untether the muse – artist relationship from the male gaze. In the dynamic between two women that Sirens and Muses depicts, there’s much less of a prescribed narrative. There’s much more freedom, much more negotiation of power dynamics. There’s more reciprocity. Karina asserts herself and participates in the making of the artwork. At a certain point, Louisa becomes worried. She’s like, What if I can’t make art without this person who’s been collaborating with me? What if she is essential to my work? One of the things that I wanted to show about the female gaze, at least as it appears in Sirens and Muses, is that it takes for granted both women’s agency in a way that the “straight men look at women” narrative doesn’t. I watched the movie Portrait of a Lady on Fire just as I was finishing the final draft of my novel. It had a deep effect on me in part because I felt that it echoed what I was doing in Sirens and Muses. It illuminates an alternative artist – muse relationship that does not involve objectification, or rather in which the objectification grants the muse agency.

BK: Can the relationship between a muse and an artist ever be platonic?

AA: It’s funny, I was just asked this question at an event I did at a university a couple of weeks ago. One student asked me, “Do you think artists and writers need a muses? Do I need a muse?” And I said, “No, absolutely not. But you need a subject. You need an obsession. It doesn’t have to be a person. And if it is a person, that person doesn’t necessarily have to be someone you’re sleeping with, or want to sleep with. But you do need a subject.”

I also told the student that you need an editor. Or you need someone who is willing to collaborate with you, and for writers, that person is often an editor. There is this idea of the solitary artist or writer who works in complete isolation and pours forth their genius onto the page or the canvas. My own experience of being a writer and publishing a book is that that is not at all true. There’s an enormous amount of collaboration involved. My husband is a painter, and even though I’m not a visual artist, he consults with me on his work. And I think that’s true of many working artists and writers — there is a lot more collaboration happening than meets the eye of the outside viewer. I wanted to illuminate that kind of collaboration in Sirens and Muses because it’s essential to making good art.

BK: Another power dynamic you explore is between the artist and the collector. In addition to being an artist and a muse, Karina is also a collector — and a stealer — of art. Unlike most of the other collectors in her world, she doesn’t want art just for its monetary value. For her, possessing a work of art is emotional or even erotic.

AA: Art — visual art in particular — has always been entwined with money, right? If you look back to the Renaissance artists like Leonardo and Michelangelo, all of them had patrons. I think that system of patronage has transformed in various ways. Today, one of the big patrons of the arts, certainly in terms of writing, is the university. A lot of writers teach or do work through universities. That’s how they fund themselves.

I did research into the economics of the contemporary art world, and it’s a pretty wild world. In the 1980s, there was an enormous boom in the art market. You started seeing artists, especially contemporary artists, selling work for eye-popping prices. Art began to function almost like a stock. You would buy a painting by an up-and-coming painter in hopes that that painter would blow up and you could flip the painting a few years later and make a ton of money. This is a whole industry now. You hear of wealthy collectors who have warehouses full of Picassos and Warhols. The art isn’t hanging on their walls. It isn’t being enjoyed by anyone. It’s just sitting in a warehouse. That’s one type of collector that’s emerged in the present-day art market.

I do think, however, that for a lot of serious collectors, like my grandparents on my mother’s side — so not Holocaust survivors, but children of Jewish immigrants who collected art, although at nowhere near the level of Karina’s parents — it was almost a religion, at least the way my mother describes it. Surrounding themselves with these aesthetic objects was a way of achieving transcendence. And I think that’s true for a lot of people who either make or collect art or have built lives in proximity to it. It takes the place of religion.

Karina is a little bit in both camps. She doesn’t view money as a dirty word. She doesn’t think it’s a bad thing for a piece of art to be valuable, and she’s not afraid to say that. But there’s also a sense in which she draws a spiritual value from the artwork her parents have surrounded her with since birth. She feels entitled to a certain painting that has always hung in her room, even though she doesn’t technically own it. She steals it, but she doesn’t see it as stealing. She’s like, No, I have a deep emotional connection to it. It’s mine.

BK: Another trend in the art world you address that seems more relevant than ever is the use of artificial intelligence. Preston’s experimentation with AI brings up the question of intention versus execution in the creation of art. To be considered an artist, is it enough to have the initial vision, or do you physically have to create the art yourself? At what point does it stop being your own work?

AA: It was wild to watch the AI art boom happen when I was writing Sirens and Muses. Since the book takes place in 2011 and 2012, I had to go back and do research to make sure that I wasn’t writing anything anachronistic. The AI art that existed at that time is like what I depict in Sirens and Muses, which is basically Preston feeding a neural network thousands of images, and then asking it to replicate those images or make images in a similar style. Some of the artwork that those neural networks created was very cool, but it did not look human-made at all. It was glitchy and mottled. It looked like computer-generated work.

The AI art that’s being created now is astounding. Recently, my husband was playing around with DALL‑E, and he said to me, “This is going to put artists out of business.” In addition to being a visual artist, he’s also an architect, and in his architecture work he actually uses AI to create architectural renderings that give the client a sense of what the building is going to look like. So it’s very useful in some ways.

Now, the flip side is that AI art is possible because those networks have been trained on real people’s art. Human beings’ art. And those human beings were not consulted. They weren’t asked for permission. That is a problem.

BK: I’m also curious to hear your thoughts about AI and writing.

AA: When it comes to writing, that is a whole other interesting kettle of fish. I am with the vast majority of writers in that it scares me, and I don’t want my writing to be used to train these programs. I don’t want anyone else’s writing to be used to train these programs.

Every book is like a window into somebody else’s brain, right? Maybe I’m hopelessly naive or way too optimistic, but I remain skeptical that an AI program can replicate the weirdness that happens in my brain! Maybe that’s arrogant of me. And maybe this will change down the line — maybe one day AI will be able to single-handedly write a great novel without any human intervention or editing. I don’t know. I will say that I’ve used ChatGPT for my writing, insofar as I sometimes use it for research. I’m writing a book right now that’s set in the area of Costa Rica where I grew up. Sometimes I’ll have questions like, What are some particular plants that grow here and their scientific names? and I’ll have ChatGPT tell me about the flora and fauna of that location. I always double-check the information it gives me, though.

BK: Were there certain pieces of art that inspired the book? How did you go about assigning different styles or media to the different artists – or did the styles come to you as inherent parts of the different characters in the same way that Karina’s Jewish background did?

AA: With some characters, I knew from the get-go what kind of art they were going to do. I always knew that Preston was going to be an internet artist doing the Tumblr and Vaporwave stuff that I saw a lot when I was in college. And I always knew that Robert would be a political artist who’d had a more traditional fine arts background. Karina’s work is loosely based on the work of Laura Owens, who is an abstract artist I’ve been a fan of for many years. She plays with all different styles and media — she’s hard to pin down. And that’s what I wanted Karina to do in her work. I wanted her to be endlessly inventive, and to play with all sorts of references to art history. I wanted her to be an undefinable artist the same way that Laura Owens is.

Now Louisa was the character whose work took me a long time to figure out. I had a serendipitous moment in maybe 2015 or 2016, when I went to a show by an artist named Cayla Zeek who grew up with my husband in Louisiana. When I lived in New Orleans in my early twenties, we were in adjacent social circles, but I’d never taken a close look at her work. I heard she was having her first solo show at a pretty young age, and I happened to go to the opening. As soon as I walked in and looked at the work, I thought, This is what Louisa does. This is her style.

As soon as I walked in and looked at the work, I thought, This is what Louisa does. This is her style… It was almost magical.

There are so few moments in writing a book when all these problems you’ve been having are solved in one fell swoop. It was almost magical. Once the book was sold and getting ready for publication, I reached out to Cayla and explained how much her art had inspired me. And Cayla actually ended up participating in the publicity process for the book. We had a preorder campaign where my publisher ordered postcards with a painting by Cayla that had inspired me of a woman who’s transforming into a bird. And we did a giveaway with those. When my book came out, my husband and mother-in-law actually commissioned a painting from her as a publication gift for me. It was so cool to not only get a major source of inspiration from an artist who I knew, but also to have her take part in the publication process. A full-circle moment.

BK:So cool. Especially given what you said about collaboration earlier. If your writing could be represented visually, what style or medium would it take?

AA: Oh my gosh. Okay. I think my ideal visual adaptation of my book would be a TV miniseries. Every author wants their book to be adopted into a movie or a TV show, so I’m not unique in this regard! But Sirens and Muses is such a visual book — not only in that it depicts lots of different art and styles, but also in that it describes the making of art. The set designers would have a lot of choices to make, in terms of How are we going to represent this particular character’s art? What is it going to look like?

BK: That attention to the mechanics of creating beauty also reminds me of Portrait of a Lady on Fire.

AA: Yes. In that movie, you also get to see the process of building a painting. You see the artist making the initial studies and sketches, and then painting it layer by layer on canvas. It’s a painterly movie in the sense that it visually depicts the way a painter’s mind works and then shows you exactly how that painting comes to life. I think Sirens and Muses is doing something similar, and I would love to see that on the screen.

BK: That would be amazing. When I first started to read your book, I saw it as a campus novel, but when I was midway through and the protagonists leave their college for New York, I wasn’t so sure it could be called that. Do you see Sirens and Muses as a campus novel?

AA: I love the campus novel. It’s a genre that I will always, always love. So if people say it’s a campus novel, I am sold. It’s a campus novel and also a post-campus novel.

I started writing the book when I was right out of college, when I really missed the life I’d had as a student. My first job out of college was as an elementary school Spanish teacher, and I did that for five years. So I went from an environment where I was around lots of people my age, where everyone was extremely interested in whatever course of study they were pursuing, and where I was having lots of deep-into-the-night conversations with smart people — I went from that environment to teaching very young children. Teaching was rewarding in a lot of ways, but I would sometimes go home and realize I hadn’t talked to an adult all day. I felt my life had been neatly and completely cleaved away from the life that I had led before. When I sat down to write this campus novel, there was a lot of nostalgia involved. It was a kind of mourning.

I spent the bulk of my twenties writing this book; I started when I was twenty-two or twenty-three, and I didn’t finish until I turned thirty. By the time I was nearing my mid- to late twenties, I had worked through my grieving process. I didn’t have the same job anymore. I’d moved a bunch of times. I had grown up a lot. And I’d had a lot of time to reflect on my own process of growing into adulthood. At that point I decided that I wanted the novel to have two halves. The first would be set in an insular campus environment. One of the things that makes the campus novel inherently interesting to me is that it’s a closed environment where people are experimenting with all different ideas and stepping on each other’s toes in various ways. And then, in the second half, I wanted to expand the novel into the real world and explore what that transition can look like for different people.

BK: Do you see Sirens and Muses as being in conversation with other campus novels?

AA: I read a lot of campus novels as part of my research and tried to learn from what their authors did. There are many campus satires that I admire. One of them is Dear Committee Members by Julie Schumacher, who was actually my thesis advisor in graduate school. Another classic is Lucky Jim by Kingsley Amos. There’s a reason that there’s so many academic satires; in a lot of ways, academia is an environment where ridiculous things happen and are taken seriously, which sometimes results in situations that are over the top. But I wanted to take academia seriously as an environment that incubates young adults.

BK: Sirens and Muses also reminds me of campus-based novels like Real Life by Brandon Taylor and Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh in how it addresses economic disparity and queer relationships.

AA: I love that you touched on both of those topics. In terms of class and money, another interesting thing about the campus is that it is a place where people of many different socioeconomic classes come together, maybe for the first time. Certainly for me, college was the first time I came into contact with people from really wealthy families. I remember my sense of shock when I realized how vast the chasm was between how they had grown up and seen the world, and how I had. The campus is a fascinating environment in which to explore those class divides. Art in particular is hugely informed by class in ways that we don’t always want to talk about. I was interested in exploring that, both from the perspective of someone from a very privileged background and from the perspective of someone who’s from a humbler background. Real Life by Brandon Taylor is another book that does that phenomenally.

I intentionally set out to write a bisexual novel. I identify as bi, and it’s a type of novel that I don’t see a ton of, even though we’re living in a golden age of queer literature.

In terms of the queer content, I intentionally set out to write a bisexual novel. I identify as bi, and it’s a type of novel that I don’t see a ton of, even though we’re living in a golden age of queer literature. So I wanted to write a novel where that particular experience of queerness was explored. I think one of the things that the book does is to capture the way that being attracted to a man and being attracted to a woman are different experiences.

Bisexuality can be a weird kind of liminal space, especially for bi people like me who are straight-passing. I am married to a cis man. My sexuality isn’t something that people know about me unless they’ve read my work or unless I’ve told them. So I wanted to write a book with explicitly bisexual characters who were navigating that liminal space. One of the really interesting things about writing this novel and talking to readers in the year and change since it’s been published, is how many women in particular are in this exact situation, quietly identifying as bi but not being seen that way. They are navigating a world where they don’t always feel like they belong in queer spaces, but they don’t feel straight, either. I’m someone who has spent a lot of time in liminal spaces because of my upbringing. I’m sort of comfortable in those spaces in between.

BK: I have one last question for you, which is inspired by a piece in the current issue of Paper Brigade. Do you think in words, images, or abstract concepts? How does your style of thinking affect you as a writer? I’m especially curious to hear your response because your novel is so visually evocative.

AA: I’m absolutely the first kind. Since I can remember, I’ve had an internal narrative. As a child, I would narrate it to myself in the third person. I’d be going about my day and think, She opens up her math notebook and solves an algebra problem. As an adult, I’ll sometimes think about a scene and work through the language in my head until I can get back to my computer and write it all down. Other times I’ll take in my surroundings and wonder how I would put them into words. Especially if I’m having a nonverbal experience — like eating something that tastes unusual to me — in the back of my mind, I’ll think, How would I describe this verbally?

I am not a particularly visual thinker at all. So part of the challenge I set for myself with Sirens and Muses was, could I write a book about a highly visual art form? Could I pull this off as a non-illustrated piece of work?

BK: Well, you definitely succeeded!

Becca Kantor is the editorial director of Jewish Book Council and its annual print literary journal, Paper Brigade. She received a BA in English from the University of Pennsylvania and an MA in creative writing from the University of East Anglia. Becca was awarded a Fulbright fellowship to spend a year in Estonia writing and studying the country’s Jewish history. She lives in Brooklyn.