Earlier this week, Leslie Maitland wrote about choosing an epigraph, the artist Gunter Demnig’s Stolpersteine project, and reconnecting branches of her family separated by the Diaspora of the Nazi years. She has been blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning.

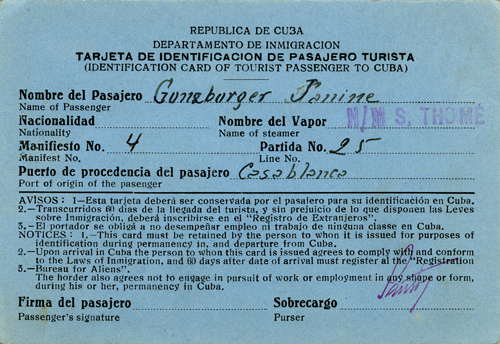

I would not be writing this today but for the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, nor could I have written my newly published book, Crossing the Borders of Time. Indeed, but for the dedicated mission of “the Joint” to save imperiled Jews from murder in the Holocaust, I would not be here at all. It was thanks to the Joint and cooperating agencies that my mother made an eleventh-hour escape from France in 1942 before the Nazis seized the country and sealed its ports. Like thousands of other Jewish refugees, she and her family fled to safety on ships chartered by the Joint from neutral Portugal. There were more than four hundred passengers with her on the Lipari, leaving from Marseille to Casablanca, where they transferred to a freighter, the San Thomé, for a voyage that lasted almost two months before the ship was cleared to land in Havana.

The steamship Lipari, on which Leslie Maitland’s mother sailed with her family from

Marseille to Casablanca on March 13, 1942.

The Joint was a curious name I heard often throughout my childhood, eavesdropping on adult conversation in New York’s German-Jewish refugee community — the so-called Fourth Reich — where I was born and lived until the age of nine. (“What joint?” I remember asking, surprised to hear my very formal German grandfather speaking what sounded to me like slang.) But my understanding and appreciation of the humanitarian agency’s vital role in saving European Jews from Hitler grew exponentially as a result of my research into my mother’s story of persecution, romance in wartime, and escape.

In this I was blessed by access to the remarkable archives of the Joint, which permitted me to study in detail the challenges it combated in securing visas, ships, and funds to rescue as many Jews as possible. In a seemingly indifferent world, even the United States had so sharply restricted entry that between the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 and war’s end in 1945, ninety percent of American visa quotas for would-be immigrants from Nazi-controlled countries in Europe went unfilled. Thus the Joint took on the mission of finding safe havens elsewhere for hunted people who were trapped in deadly situations.

In my mother’s case, through internal Joint reports, I would learn for the first time of dangers that threatened her family even after the agency had managed to get them out of France. They had been at sea for more than four weeks when Cuban president Fulgencio Batista abruptly revoked permission for the San Thomé passengers to land. Once again, it was the Joint that saved them. Rushing into action, the Joint provided sufficient international pressure and inducements to prevent the San Thomé from meeting the same cruel fate as the St. Louis, whose passengers — barred from landing in Cuba or the United States three years earlier — had been sent straight back to Europe to face the Nazis.

In this I was blessed by access to the remarkable archives of the Joint, which permitted me to study in detail the challenges it combated in securing visas, ships, and funds to rescue as many Jews as possible. In a seemingly indifferent world, even the United States had so sharply restricted entry that between the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 and war’s end in 1945, ninety percent of American visa quotas for would-be immigrants from Nazi-controlled countries in Europe went unfilled. Thus the Joint took on the mission of finding safe havens elsewhere for hunted people who were trapped in deadly situations.

In my mother’s case, through internal Joint reports, I would learn for the first time of dangers that threatened her family even after the agency had managed to get them out of France. They had been at sea for more than four weeks when Cuban president Fulgencio Batista abruptly revoked permission for the San Thomé passengers to land. Once again, it was the Joint that saved them. Rushing into action, the Joint provided sufficient international pressure and inducements to prevent the San Thomé from meeting the same cruel fate as the St. Louis, whose passengers — barred from landing in Cuba or the United States three years earlier — had been sent straight back to Europe to face the Nazis.

The tourist identification card provided to Leslie’s mother, Janine Gunzburger, aboard

the San Thomé for debarking in Cuba

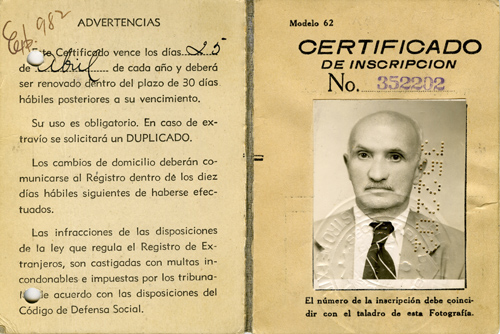

Then again, after the San Thomé refugees were allowed to disembark, the Cuban government locked them into a detention camp, Tiscornia, where they spent months inexplicably confined under terrible conditions, while forced to pay grossly inflated daily fees. Here, too, it was the Joint that fought incessantly to improve their lot, to bring them food and supplies, and ultimately to win the refugees’ release. The files of the Joint offered me eyewitness descriptions of everything that happened. Through once-confidential letters and memoranda, I sat at tables where its tireless staff negotiated strategies for overcoming obstacles and crises, as they worked to help the stricken refugees reclaim lives of freedom and normalcy.

Once freed from the Cuban detention camp where the family spent five months, Leslie’s grandfather, Samuel Sigmar Gunzburger, was required to purchase a Cuban Defense Ministry foreign registration booklet that included his fingerprints.

According to Linda Levi, the Joint’s director of Global Archives, I was one of approximately 850 researchers — scholars, journalists, filmmakers, authors, artists, and genealogists from twenty-eight countries — who annually seek permission to delve into its records. Housed in New York City and Jerusalem, the archives represent a vast repository of information gathered since the agency’s founding in 1914 by wealthy German-Jews in America to aid impoverished communities in Palestine and Eastern Europe struggling through the First World War. Included in the archives are more than three miles of text documents; 1,100 audio recordings of oral histories, broadcasts, and historic speeches; 100,000 photographs; 1,300 video recordings; and data relating to 500,000 names.

Now, just this spring, in a gift to the general public and all researchers, the Joint has started making this material available online through its archival website: http://archives.jdc.org. With funds donated by Dr. Georgette Bennett and Dr. Leonard Polonsky, the project has already digitized records dating from the agency’s founding up through 1932. In a telephone interview, Ms. Levi told me that the effort is continuing, and full archives covering the World War II period should be digitized by year’s end. Some of those Holocaust-era documents are expected to be online as early as this summer, she said, adding to what is already there.

Besides the professional researchers who will clearly benefit from the expanded website, Ms. Levi noted, members of the general public have consistently turned to the Joint seeking answers regarding family members, all too often dead or missing.

“Jews have questions about their pasts,” she said. “There is a hole somewhere they’re longing to fill. There is something intensely powerful about finding information about one’s family in a document in an archive. I’ve seen people burst out crying.”

Meanwhile, as the agency’s online archives grow, so too do its endeavors around the globe. Its work goes on today in more than seventy countries, where it strives to alleviate suffering, rescue endangered Jews, strengthen Jewish life, and provide relief for Jews and non-Jews who fall victim to disasters. It is my hope that through the online archives, the children and grandchildren of the people served and saved may one day learn their stories and join me in saying thank you to the Joint.

Leslie Maitland is a former award-winning reporter and national correspondent for The New York Times who specialized in legal affairs and investigative reporting. Her newest book, Crossing the Borders of Time: A True Story of War, Exile, and Love Reclaimed, is now available.

Leslie Maitland is an award-winning former New York Times investigative reporter who covered the Justice Department. A graduate of the University of Chicago and the Harvard Divinity School, she spent a decade researching this book, traveling to every location involved to plumb archives and interview witnesses. She appears regularly on the Diane Rehm Show on NPR to discuss literature. Leslie Maitland is available to be booked for speaking engagements through Read On. Click here for more information.