Earlier this week, Judy Batalion shared her experience of showing her mother her memoir about their relationship. She is blogging here all week as part of the Visiting Scribe series on The ProsenPeople.

My memoir, a tale of surviving the survivors, centers on how I endured my Mom’s and Bubbie’s hoarding. I hated the embarrassing piles — stashes of dresses procured from bargain-basements, frozen bananas waiting for their supposed transformation to loaf, mountains of handbags haggled over at bazaars across 1980s Montreal — that made me feel emotionally and physically blocked from my family. I spent my adulthood decluttering and running away. My flight, to England, to work as an art historian in cut-glass British museums and white-walled galleries, was in opposition to my family. But this militant minimalism was also, to some degree, in opposition to my Jewishness. “Curator” was the least Yiddish word I knew and I wanted in.

Hoarding is thought to affect a staggering 3 – 4% of the American population. As Randy Frost and Gail Steketee point out in Stuff: Compulsive Hoarding and the Meaning of Things, hoarding behaviors are not necessarily related to a history of war or deprivation. However, many Jews tell me they can relate to my story. “My great-uncle-in-law was a survivor and has a house full of tomato sauce!” or “Oy, my poor newspaper-collecting cousin…” I wonder if accumulation is a Jewish tendency, in reaction to the Holocaust and in a broader way. We’re familiar with stereotypes about excessive calories, volume, words, and I sense it’s similar for objects. You’d think a nation known for thousands of years of nomadism would have perfected the art of living lightly, but it appears that Jews have lots of things. Nu, why?

Hoarding is thought to affect a staggering 3 – 4% of the American population. As Randy Frost and Gail Steketee point out in Stuff: Compulsive Hoarding and the Meaning of Things, hoarding behaviors are not necessarily related to a history of war or deprivation. However, many Jews tell me they can relate to my story. “My great-uncle-in-law was a survivor and has a house full of tomato sauce!” or “Oy, my poor newspaper-collecting cousin…” I wonder if accumulation is a Jewish tendency, in reaction to the Holocaust and in a broader way. We’re familiar with stereotypes about excessive calories, volume, words, and I sense it’s similar for objects. You’d think a nation known for thousands of years of nomadism would have perfected the art of living lightly, but it appears that Jews have lots of things. Nu, why?

There are practical reasons. A priest recently came over for Friday night dinner and confessed his envy. It’s easier to get a younger demographic to follow Jewish custom, he explained, because most of its rituals take place, not in the unpopular church, but in the home. But for those rituals, I thought, you need ritual items. (See: formal set of pareve Passover salad tongs.)

There are emotional reasons, I guessed. Our baggage, when unpacked, might function as an aggressive attempt to lay roots. When we settle, we do so with a vengeance. Hey, I’m planted here, along with 300 kippahs collected at bar mitzvahs since the 1960s. Possessions can form a protective wall. We feel cuddled and coddled surrounded by our things, womby and warm.

I had a nosh with environmental psychologist Sally Augustin who confirmed that our belongings make us feel good, in different ways than I predicted. She explained that objects are important for identity. “We didn’t evolve in a minimalist box,” she said. Our trinkets remind us of what we value, how we see ourselves, what image we want to project to the world, and who we want to be. On top of this, objects provide social clues. We make conversation around a boot collection. We subconsciously act more distanced with people whose surroundings are sparse because we are distracted, confused about who they are. Could it be a vicious substance circle? Jews are talkative, and have tchotchkes, so they’re talkative… I’d always seen a hoard as a blockade, but now I considered how our clutter might enable connection.

Of course, one chat wasn’t enough for this Jewess. I called my friend and professional organizer Elizabeth Savage who told me of a client of hers who madly collected purses. “Holocaust roots,” she said, knowingly. I knew. Bubbie had hundreds; the “pushkin” is the meta-symbol of safety. “In our mobile and transient culture, everything moves so quickly. We cling to our things because we don’t want to die!” Liz cried. Survivors or not, our objects comfort us.

Makes sense. Stuff links us to our pasts, marks our memories, challenges the inevitable demise of our biodegradable beings. Our stashes can be a hassle to store, organize and use, which is perhaps a little bit like Jewish heritage. It’s there, it’s hidden, it’s out, it’s too much, but ultimately, it feels good too.

Judy Batalion is the author of White Walls: A Memoir About Motherhood, Daughterhood, and the Mess In Between.

Related Content:

- Joshua Cohen: Self-Surveillance

- Talia Carner: “Second Generation” Forever

- Inventing Jewish Ritual by Vanessa L. Ochs

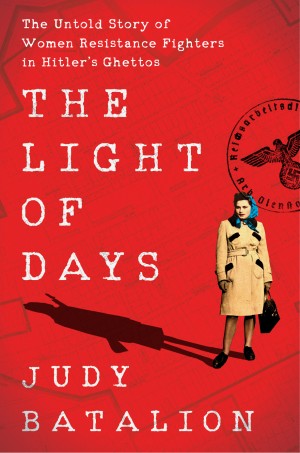

Judy Batalion is the New York Times bestselling author of the highly-acclaimed The Light of Days: The Untold Story of Women Resistance Fighters in Hitler’s Ghettos, published by William Morrow in April 2021. The Light of Days has been published in a young readers’ edition, will be translated into nineteen languages, and has been optioned by Steven Spielberg for a major motion picture for which Judy is co-writing the screenplay. Judy is also the author of White Walls: A Memoir About Motherhood, Daughterhood and the Mess in Between, optioned by Warner Brothers, and her essays have appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Forward, Vogue, and many other publications. Judy has a BA in the History of Science from Harvard, and a PhD in the History of Art from the Courtauld Institute, University of London, and has worked as a museum curator and university lecturer. Born in Montreal, where she grew up speaking English, French, Hebrew, and Yiddish, she lives in New York with her husband and three children.