Earlier this week, Wendy Lesser wrote about Louis Kahn’s Jewish identity why she chose to write You Say to Brick: The Life of Louis Kahn. Wendy is guest blogging for the Jewish Book Council all week as part of the Visiting Scribe series here on The ProsenPeople.

Early on in my interviewing for the book that would become You Say to Brick: The Life of Louis Kahn, I talked to a Philadelphia architect, David Slovic, who had been both a student and an employee of Kahn’s. “Here’s what I want to know,” Slovic mused toward the end of our conversation. “We all went to the same schools. We all had the same training. Why did he turn out to be Louis Kahn and the rest of us didn’t?””

“That’s what I’m hoping to answer in my book,” I said.

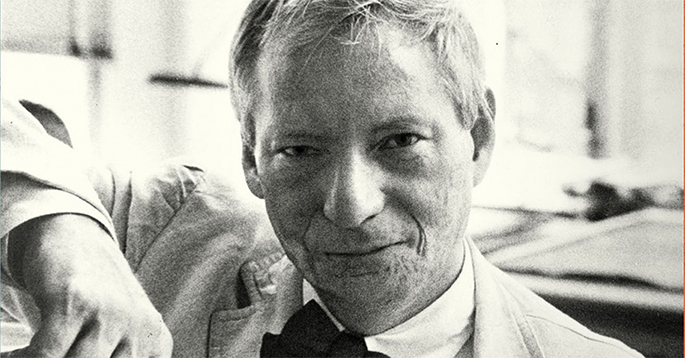

But when you write a biography of an artist — any artist — the effort to find the sources of their inspiration or the key to their work is only part of what you are doing. You are also trying to understand a human being as a fellow human, though in ways that are utterly different from what you might apply to the people around you. I know both more and less about “Lou” than I will ever know about my best friend, my husband, or my own child. I never met Kahn, but I would recognize his voice, his handwriting, perhaps even his style of sketching or his way of putting words together. I probably know more about his fears and dreams and desires than I know about my own; I certainly know more about his death (which was, in its own way, quite mysterious) than I will ever know of my own. And though some of the information I painstakingly gathered helped me to understand his buildings, a great deal of it was just interesting for what it told me about him as a person.

I think now of three key moments in the research process, moments that made me feel I was drawing especially close to the man behind the architect. One was a four-page letter written to Lou in 1945 by his younger brother, Oscar Kahn, when they were both in their early forties. (I learned about the letter from Nathaniel Kahn, who told me to look it up in the Architectural Archives at Penn.) I won’t reproduce the letter here — it appears in full in my book — but suffice to say it gives the clearest, most incisive analysis of Lou’s personality I have yet come across.

The second item was a series of test results that came out of a study run at UC Berkeley in the late 1950s, a “creativity study” in which Kahn was one of the participating architects. No restrictions were ever put on this material, so the kindly people at the Institute for Personality and Social Research — the inheritor of this research — gave me Lou’s Rorschach results, his Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, his Thematic Apperception Test, his psychological interview transcripts, and a whole host of other materials he never imagined would see the light of day. Some of it was uninterpretable garbage, but amid the rubbish were a number of deep and incisive revelations, including key observations about his childhood, his parents, and his relationship to his own work.

And then there was the dream Lou scribbled on the back of his BOAC boarding pass during one of his final visits to Bangladesh in January of 1973. His older daughter, Sue Ann Kahn, handed it to me with a bunch of family papers she had accumulated but not necessarily read. It was written in microscopic handwriting I had to decipher with the aid of a magnifying glass. Again, I can’t really go into the dream and its meaning in this brief space, but what I remember is the uncanny sensation I had when first reading it — almost as if I were touching Kahn’s mind with my hand.

Still, all the personal insights I’ve gained do not really explain why Louis Kahn became the great architect he did. There is always a gap between individual personality and artistic achievement, and with an architect the gap is even greater than usual, because so many factors beyond his own character (collaborators, clients, money, the site itself, various social and historical forces, the state of technological development, etc.) influence the outcome of his work. So I can’t make a case that my biography will fully reveal, for David Slovic or anyone else, the true sources of Kahn’s architecture.

What I can say is that there was a moment in the process when I suddenly became aware of a felt connection between the individual man — that unusual person who carried on all those intense, unconventional love affairs — and the marvelous buildings he produced. When I visited the home of his younger daughter, Alexandra Tyng, she showed me a picture of Lou that hung on her wall, a photograph taken in 1936 of him shooting a bow and arrow at the Brookwood Labor College. As I looked at him standing there in his skimpy archery costume, with his well-muscled body and his confident stance, I thought, Yes: that is the feeling his architecture gives us, the sense that we are fully inhabiting our bodies. His buildings make us feel we are contained within a vast space, at once tenderly embraced and freed into a kind of elevated exaltation, as if the massive environment is lifting us up and making us larger even as it protectively acknowledges our merely human size.

What I can say is that there was a moment in the process when I suddenly became aware of a felt connection between the individual man — that unusual person who carried on all those intense, unconventional love affairs — and the marvelous buildings he produced. When I visited the home of his younger daughter, Alexandra Tyng, she showed me a picture of Lou that hung on her wall, a photograph taken in 1936 of him shooting a bow and arrow at the Brookwood Labor College. As I looked at him standing there in his skimpy archery costume, with his well-muscled body and his confident stance, I thought, Yes: that is the feeling his architecture gives us, the sense that we are fully inhabiting our bodies. His buildings make us feel we are contained within a vast space, at once tenderly embraced and freed into a kind of elevated exaltation, as if the massive environment is lifting us up and making us larger even as it protectively acknowledges our merely human size.

Wendy Lesser is a member of American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the founding editor of The Threepenny Review. She has received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, National Endowment for the Humanities, the Dedalus Foundation, and the New York Public Library’s Cullman Center for Scholars.

Related Content:

- Jenny Feldon: How I Became an Accidental Housewife and Ignored the Labels

- Julian Voloj: The Menschlich Schmuck

- Matthew Baigell: We’re Living in a Golden Age of Jewish American Art and We Don’t Really Know It

Wendy Lesser is an American critic, novelist, and editor based in Berkeley, California. She is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the founding editor of The Threepenny Review. Wendy has received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, National Endowment for the Humanities, the Dedalus Foundation, and the New York Public Library’s Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers.