The introduction to Roz Chast’s memoir, Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant, pictures an eight-panel, full-color comic of an aging couple sitting on the sofa beside their daughter. As the daughter precariously and awkwardly attempts to involve her parents in a talk about “things” (“What kind of things?” they ask; “Plans,” she responds, adding, “I have no idea what you guys want!”), the couple throws their hands in the air, looks blankly at her, shrugs, and even laughs. “Am I the only sane person here???” she finally asks, exasperated.

This exasperation is a persistent theme in Chast’s memoir, which recounts her relationship with her parents, and especially the last years of their lives, in excruciatingly honest detail. An only child, Chast finds herself bearing the brunt of her parents’ transition from “the sphere of TV commercial old age” to “the part of old age that was scarier, harder to talk about, and not a part of this culture.” Her parents’ adamant refusal to deal with declining physical and mental health becomes an added burden, and she finds herself experiencing conflicting emotions as she commutes from Connecticut to their increasingly neglected and difficult to navigate Brooklyn apartment. Chast eventually transitions the two into assisted living facilities near her home, recounting the “painful, humiliating, long-lasting, complicated, and hideously expensive” trials that account for what she calls “the end.”

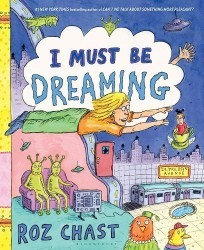

Chast is best known for deceptively buoyant New Yorker cartoons that picture characters and objects in everyday settings, but which are mired in a sharp sensibility often looking to uncover those “harder to talk about” spheres. In this memoir she incorporates her familiarly whimsical humor alongside prose-heavy pages detailing the grief and guilt of facing what can become, for many, one of life’s most challenging and solitary ordeals. To be able to recount the story of your parents’ deaths might seem, to some, an overwhelming feat not worth the pain incurred. But, as readers, witnessing someone grapple with what feels impossible to discuss is, perhaps, the first step towards learning how to talk about “things.” And for that, this reader is deeply grateful.

Tahneer Oksman is a writer, teacher, and scholar. She is the author of “How Come Boys Get to Keep Their Noses?”: Women and Jewish American Identity in Contemporary Graphic Memoirs (Columbia University Press, 2016), and the co-editor of The Comics of Julie Doucet and Gabrielle Bell: A Place Inside Yourself (University Press of Mississippi, 2019), which won the 2020 Comics Studies Society (CSS) Prize for Best Edited Collection. She is also co-editor of a multi-disciplinary Special Issue of Shofar: an Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies, titled “What’s Jewish About Death?” (March 2021). For more of her writing, you can visit tahneeroksman.com.