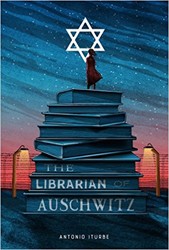

The true story of Dita Kraus, a young Jewish woman who survived Auschwitz, was fictionalized in Antonio Iturbe’s Spanish-language novel, translated into English in 2017. (A Delayed Life: The True Story of the Librarian of Auschwitz is Kraus’s own memoir, and The Children’s Block is a fictionalized account of the same events by her husband, Otto Kraus.) Now, Salva Rubio and Loreto Aroca have interpreted Iturbe’s work in a graphic novel for young adults. They have simplified some of the history behind Dita Kraus’s suffering and liberation, but the impact of the original narrative remains. As in any account of the Holocaust, larger questions arise about why and how the genocide of Europe’s Jews could have occurred. Readers will learn about the anomalous BIIb section of the camp, where families and children were briefly deceived about their ultimate fate in order to conceal the truth from the outside world. While the ending of the graphic novel offers some cautious notes of happiness, the text and pictures nevertheless convey the harsh realities of the infamous death camp.

Like most of the Nazis’ Jewish victims, Dita’s family in Prague is unprepared for the upheaval. She is presented as a bookish child with loving parents. She reads all the time, and her father delights in spinning a globe to teach her geography. But this world is about to end. Aroca captures the Nazi invasion in a series of panels: first boots, then motorcycle wheels, then soldiers, then the swastika flag. Rubio succinctly expresses Dita’s response: “ … that was the day she started to fear men.” Briefly, in a visit to the Jewish cemetery, Dita fantasizes that the mythical golem of her native city will protect its Jews. Her dream soon vanishes.

Although Auschwitz is clearly a location of physical and mental torment in the novel, there is relatively minimal focus on its worst horrors. Rubio does not avoid Josef Mengele’s grotesque medical experiments, allusions to gas chambers, and an image of the crematoria, but most of the book takes place in the children’s block and section BIIb. When Dita first arrives, she is relieved that the situation is not worse. She meets the mysterious Freddy Hirsch, a Zionist who has taken on the role of educating the children permitted to live, if only briefly, in the camp. Although she reveres Freddy, her confusion about his motives, and his willingness to give children hope when he knows they will be killed, cause her great anguish.

In the end, the Nazis’ machinations of deceit are revealed, and they send the ostensibly protected residents of BIIb to their deaths. As they are deported, the grays and earth tones that are most prominent in the book alternate with flashes of red. Then, a pit of bodies takes up a full page. The author and illustrator move, perhaps ambivalently, between images of ruin and suggestions that a “miracle” saved Dita, that a “will to live” played a role in her survival. The thought of such redemption is often tempting to authors analyzing the Holocaust. Here it is subtle, appearing in descriptions of Dita’s life after she has been freed. But despite its more ambivalent elements, this graphic novel is devastatingly powerful.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.