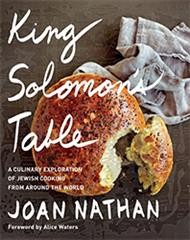

Joan Nathan has a new cookbook out this week! With the release of King Solomon’s Table: A Culinary Exploration of Jewish Cooking around the World, Joan is guest blogging for the Jewish Book Council all week as part of the Visiting Scribe series here on The ProsenPeople.

One of the ideas that I have wrestled with throughout my career is the question of what is “Jewish food”. Working on my latest cookbook, King Solomon’s Table: A Culinary Exploration of Jewish Cooking around the World, has at last answered that question for me.

The special quality of Jewish food first came to me years ago through the cookbook author Lynn Rossetto Kasper, former host of the radio program The Splendid Table. Lynn, when talking about the food of Emilio Romagna, said that this Italian regional cuisine was rooted in the land. I immediately thought that the same could not be said for Jewish food: our cuisine may indeed be metaphorically rooted in the land of Israel but, in truth, being tied to the soil of just one land is not a component of Jewish cooking.

To my mind, Jewish food is tied more strongly to its dietary laws and many food-centered holidays. Even if Jews are not very observant, they know in the back of their minds that kosher laws exist, and that many of these rules go back Biblical times, influencing how we all eat. Indeed, these dietary laws have been a comfort to so many of us through our lives and are a very important component of what is called Jewish food.

The second component that defines Jewish cuisine is that since people first learned about seafaring vessels from the Phoenicians, as it says in the Bible, Jews have gone out in search of food, jewels, and precious stones for Solomon’s Table. Jews have always looked for new flavors and have eagerly incorporated these novel foods (provided they were kosher) into their diet.

The third component is the fact that, as a people, Jews have been displaced again and again throughout history. In moving to Spain, then being kicked out of Spain, and then moving from there throughout the Mediterranean and to the Americas, the Jewish people have had to adjust to new ingredients and new homes.

The haroset we place on our tables at Passover reflect this Diasporic legacy. In some areas we use romaine lettuce for our bitter herbs while in others we use horseradish, both red and white. In places like Maine we have haroset made out of blueberries; in Iran, this symbolic spread is infused with the flavors of almonds and cardamom. Jewish foods vary geographically with different customs, different vegetables, different main dishes, and different desserts, but always retain their connection with the symbolic and the sacred in Jewish traditions.

In a sense all three of these components are interrelated. I remember going to the Russian Embassy in Washington, D.C. for dinner one night and there we feasted on a zakuska made of smoked salmon, blinis, chopped eggs, and scallions, a dish familiar to my husband with his Eastern European background. At this dinner, however, the Russian Ambassador served this recipe alongside beef stroganoff and other dishes that combined meat and dairy.

Treif considerations aside, my husband couldn’t help but remark on how very Jewish all the food was. He didn’t believe me when I told him that what he considered to be “Jewish food” was really just Russian food made with either dairy or meat (but not both). A wandering cuisine since it began in the Middle East, Jewish food was simply what Jews made their own in whatever part of the world in which they found themselves. The very Jewish-tasting Russian zakuska was no exception.

Joan Nathan is a frequent contributor to The New York Times and other publications. She is the author of eleven books, including Jewish Cooking in America and The New American Cooking, both of which won both James Beard Awards and IACP Awards.