Yesterday, Eric L. Muller asked: What does a concentration camp look like? He will be blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning.

My new book Colors of Confinement presents dozens of stunningKodachrome photographs of everyday life inside the barbed wire confines of theHeart Mountain Relocation Center in 1943 and 1944. The photographer was BillManbo, a thirty-something auto mechanic from Hollywood, California, who waslocked up there in September of 1942 along with his family and his wife Mary’sfamily. Although Manbo was not a documentary photographer, his pictures (andthe fact that he was allowed to take them) capture much of what was uniqueabout the confinement sites that the U.S. government created for the WestCoast’s ethnically Japanese population during the war.

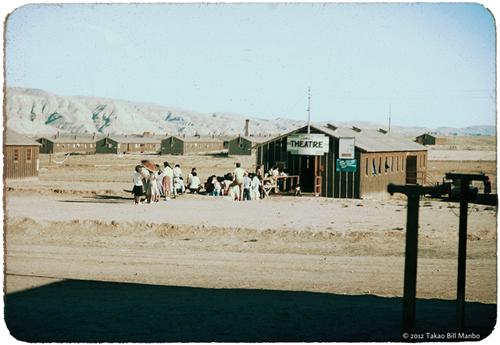

On theone hand, the photographs reveal a population held captive in a desolate desertcompound with no conceivable justification other than suppositions about racialloyalties.

On the other hand, the photos reveal that the population’s captorsallowed them a surprising number of freedoms, including the freedom to engageopenly in Japanese cultural and religious activities … and the freedom towander around taking pictures of them.

Of the first point — the injustice of the mass incarceration —there can be no doubt. Months after the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor,the U.S. government uprooted and exiled some 120,000 people of Japaneseancestry — citizens and resident aliens alike — for reasons that includedbiological racism and economic opportunism. The U.S. Army general whoordered the roundup explained that U.S. citizens were just as dangerous as theirJapanese immigrant parents because the “Japanese race” was an “enemy race” inwhich the “racial strains” ran “undiluted” in the blood of the secondgeneration. White-dominated agricultural interests on the coast that hadlong sought the ouster of successful Japanese farmers saw an opportunity to putthem out of business and were among the most forceful advocates for massexclusion. It would be a distortion to say that the ouster of theJapanese from the West Coast and the ouster of the Jews from Germany had exactlythe same causes, but it would also be a mistake to miss the fact that the twomass deportations shared key motives. U.S. Supreme Court Justice FrankMurphy noted this in a 1943 decision when he wrote that the government’streatment of Japanese Americans bore “a melancholy resemblance” to Germany’s treatment of its Jews.

And yet there can also be no doubt that the War RelocationAuthority (WRA), the civilian agency responsible for confining JapaneseAmericans in the camps, did not share the ugliest views of those who had calledfor and overseen their removal from the coast. The WRA was certainlycapable of manipulation and blunt repression of its charges, but italso often sought to help them make their imprisoned lives more bearable andless dreary, healthier and more productive, and less likely to end up in astate of permanent government dependency. This is why Bill Manbo’sphotographs include images of dancing kimono-clad women, and of sumo-wrestling men, and of inmates lined up for a matinee showing at one of the camp’s two movie theaters.

This helps us appreciate what is arguably the most amazing thingabout this collection of photographs (apart from the fact that they’re incolor): a prisoner had the freedom to walk around the camp and take them.

In the spring of 1942, before Japanese Americans were forced fromtheir homes, cameras (like short-wave radios, binoculars, and other such items)were contraband. In the late winter of 1943, however, the WRA came torealize that camp inmates would have an easier time adjusting to life behind barbedwire if it restored to them the ability to take family photos and documenttheir lives with cameras. Not many had the wherewithal to reclaim theircameras, and fewer still had the skill and commitment to shoot in Kodachrome,then an expensive technology that was just seven or eight years old. BillManbo did, though, and it’s because he did — and because the WRA trusted himenough to allow him — that we have these beautiful glimpses of life at HeartMountain.

Eric L. Muller will be blogging here all week.Images from COLORS OF CONFINEMENT: RARE KODACHROME PHOTOGRAPHS OF JAPANESE AMERICAN INCARCERATION IN WORLD WAR II edited by Eric L. Muller. Copyright © 2012 by the University of North Carolina Press. Photographs by Bill Manbo copyright © 2012 by Takao Bill Manbo. Published in association with the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. Used by permission of the publisher. www.uncpress.unc.edu

Eric L. Muller is Dan K. Moore Distinguished Professor in Jurisprudence and Ethics at the University of North Carolina School of Law and director of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Center for Faculty Excellence. His newest book, Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II, is now available.