In November, David Evanier wrote about Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and the reissuing of his novel Red Love. He is blogging here this week for Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning.

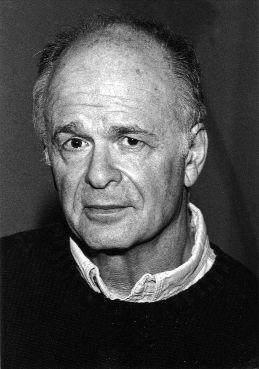

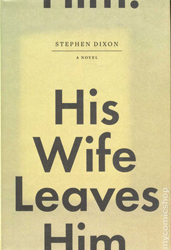

Stephen Dixon is, in my opinion, the best and most overlooked American Jewish fiction writer in the country. If I left out “Jewish,” he would still be the best. He has just published his 32nd book, a novel entitled His Wife Leaves Him, which is partly based on the death of his own beloved wife. Like Philip Roth, Cynthia Ozick, Thomas Beller, Jennifer Belle, Jonathan Lethem, Bruce Jay Friedman, and such predecessors as Saul Bellow, Henry Roth, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Daniel Fuchs, Grace Paley, Tillie Olsen, and Wallace Markfield, Dixon’s Jewishness is not an orthodox or institutional one, but simply a fact that informs and haunts much of his work. It is hard to understand Dixon’s obscurity; he’s a two-time National Book Award finalist and has won four O. Henry Awards, a Guggenheim Fellowship for fiction, and an American Academy of Arts and Letters Literature Award. In 1994 the Boston Globe wrote that “It will take writers twenty years to catch up with what Stephen Dixon is doing.”

Stephen Dixon is, in my opinion, the best and most overlooked American Jewish fiction writer in the country. If I left out “Jewish,” he would still be the best. He has just published his 32nd book, a novel entitled His Wife Leaves Him, which is partly based on the death of his own beloved wife. Like Philip Roth, Cynthia Ozick, Thomas Beller, Jennifer Belle, Jonathan Lethem, Bruce Jay Friedman, and such predecessors as Saul Bellow, Henry Roth, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Daniel Fuchs, Grace Paley, Tillie Olsen, and Wallace Markfield, Dixon’s Jewishness is not an orthodox or institutional one, but simply a fact that informs and haunts much of his work. It is hard to understand Dixon’s obscurity; he’s a two-time National Book Award finalist and has won four O. Henry Awards, a Guggenheim Fellowship for fiction, and an American Academy of Arts and Letters Literature Award. In 1994 the Boston Globe wrote that “It will take writers twenty years to catch up with what Stephen Dixon is doing.”

His output is mind-boggling: in addition to his novels, he has published hundreds of stories and is completing a new book, Late Stories, with hundreds more. Nevertheless, Dixon is not about quantity or longevity. Dixon is about freshness and quality. Among his gifts — which include narrative inventiveness without a trace of pretension or convolution, a hilarious sense of humor, and a memory that seems to evoke every single thing that has ever happened to him — he writes the most moving and lasting love stories I have ever read. Among them are his immortal story Sleep, in which the narrator imagines, with infinite pain and loss, the death of his wife.

And now we have in His Wife Leaves Him, perhaps the most complete love story ever written in the history of American letters. And it too is a story told in the face of death. Martin’s wife, still young, is diagnosed with a degenerative disease that, over the years, is unrelentingly cruel and ultimately fatal. I am certain that American literature has never created a husband who gives of himself so deeply, so fully, taking care of his wife even to the point of physical exhaustion. And it is a story told without false sentimentality or embellishment, which renders it all the more touching and believable.

Martin Samuels, the protagonist, has spent the first forty years of his life bumbling about — as a bartender, actor, reporter, wanderer in Paris, but always a dedicated writer — in search of a true love.

When he encounters Gwen, he finds everything he has been looking for: a truly beautiful, gentle but strong woman of exquisite kindness, sensitivity and literary sensibility, a person of the highest moral standards who shares his values and passions and is ready to start the family he has been yearning for.

She is a translator of the Russian literature he reveres, with a profound knowledge of the literature of the Gulag, Nazism and the inspiration of the Soviet Jewry movement. And she is Jewish, not a small matter to him. Gwen says, “Though I’m by no means a religious or observant Jew — at most, I’ll buy a box of egg matzos for Passover, though I’ll continue to eat bread and rice over the holiday — my Jewish identity is very strong and important to me because of my family history. In fact, the reason I’ve never been seriously involved with Gentile men since high school, or really only one and not for long, is because I never felt they could understand my experience of growing up as the daughter of Holocaust survivors.”

Although he is Jewish, he has not dated a Jewish woman seriously before. “That’s why I said before,” he tells her, “that I was glad you were Jewish. Fact is, for want of a better word this moment — maybe because I am so thrilled — I’m thrilled.” Everything about Gwen fills Martin with gratitude, and it will be a procreative life filled with their children, beautiful environments (Maine, Riverside Drive) and a passionate immersion in creative work — work they both engage in. Martin cries at his own wedding. His mother says, “It shows how sensitive you are and how much she means to you. I’m only saying I never saw or heard of any groom doing it before, and I’ve been to plenty of weddings. I can just imagine how you’ll react when your first baby comes out and you’re in the room.” This kind of dialogue, affectionate, funny and sad, richly steeped in a lived history, is totally representative of Dixon.

The novel is a summing up of the totality of a marriage, its incredible joys, epiphanies, smoldering sensuality, tenderness and moments of frustrated rage as Martin is engulfed, in the later stage of the marriage, in an endless round, night and day, of ministering to Gwen in her terrifying decline. And Dixon summons Gwen back to life unforgettably through her dialogue, and we see a precious person, a brilliant character, rendered real and palpable.

The novel is a summing up of the totality of a marriage, its incredible joys, epiphanies, smoldering sensuality, tenderness and moments of frustrated rage as Martin is engulfed, in the later stage of the marriage, in an endless round, night and day, of ministering to Gwen in her terrifying decline. And Dixon summons Gwen back to life unforgettably through her dialogue, and we see a precious person, a brilliant character, rendered real and palpable.

It’s hard to believe that Dixon’s encyclopedic memory has left a single thing out of this account of an extraordinary marriage. Dixon manages it not only through memory, but with a particularly intimate, vulnerable style of writing, a writing of deep feeling in which nothing is held back, even though it is artfully shaped and the ordinary details and tedium of life are transmuted by a master novelist. Dixon is an obsessed writer (great ones usually are) but he is not solipsistic; his work encompasses everyone he encounters and paints with vivid colors. He blankets the reader with specifics, but specifics so unique and compelling that they have universality. His work will stand as a penetrating record of what a man’s love for a woman can be, and what it means to be a humane, sensitive, flawed, passionate participant in life in our time.

David Evanier has published seven books and has received the Aga Khan Fiction Prize and the McGinnis-Ritchie Short Fiction Award. He was the founding editor of the literary magazine, Event, and the former fiction editor of The Paris Review. His novel Red Love was recently published as an e‑book.

Related Content:

- West and Schwartz, Dreaming at the Movies (Ilan Mochari)

- Writing the Tradition (Daniel Torday)

- Reading List: On Writing Jewish Literature and Being a Jewish Writer

- Reading List: Writers on Other Writers and Books

David Evanier has published eight books and has received the Aga Khan Fiction Prize and the McGinnis-Ritchie Short Fiction Award. He was the founding editor of the literary magazine, Event, and the former fiction editor of The Paris Review. Read more about David Evanier here.

2013

The Best Overlooked American Jewish Novelist