Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

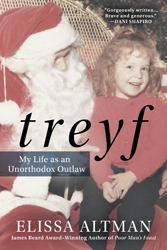

Elissa Altman’s second memoir, Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw, comes out this week. To celebrate her new book’s release, Elissa is guest blogging for the Jewish Book Council all week as part of the Visiting Scribe series here on The ProsenPeople.

As I write this, I am sitting on a screened-in porch in a small cottage overlooking the Kennebec River in coastal, central Maine. My rakish terrier mutt, Petey, is asleep at my feet in a beige, ever-so-slightly worn Orvis bed that cost as much a pair of Gucci loafers; my partner, Susan, is in the kitchen, planning the third lobster dinner we’ve had since we’ve been here. The scene is something right out of the fall L.L. Bean catalog: there are small bottles of bug spray in every room; the cottage’s scuffed, utilitarian dinnerware is decorated with tiny blue lighthouses; there is a slight edge of chill to the air — it came on suddenly, with the changing of the calendar from August to September — and for the first time since we arrived, I have to wear a fleece vest with my shorts and flipflops. We love it here. We love the people, the land, the water, the food, the literature, the nature, the history. We’ve been coming to Maine for two weeks every September for a few years now. We have close friends and family who live here year-round and we will, most likely, eventually make the state our home.

So when I was asked to do a reading from my new book, Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw, up in bucolic Rockport a few days ago, I was thrilled and delighted and completely honored. And then I realized that the odds of anyone knowing what the word treyf meant — literally and figuratively; halachically and metaphorically — were, to say the least, slim. Here, in the land of the lobster, the shrimp, the mussel, the wild oyster, the all-you-can-eat-fried-clam-supper, the bean-and-ham-community-church-buffet, I would be standing in front of a roomful of gorgeous Mainers tan from a summer spent on the water — the women wearing nary a drop of makeup beyond a slick of lipgloss, the men in ancient, salt-caked Docksiders and polo shirts with fraying collars — in the least religious state in America, talking about Shabbos, and the time my bubbe from the old country fed me boiled calves’ brains the day after I saw Young Frankenstein in 1974, the Coney Island parachute drop hovering in the distance less than a mile from the schmaltz-soaked low-rise Brooklyn apartment building where she lived for sixty years.

“What will you read?” Susan asked as she drove us north through Wiscasset, past Red’s famous lobster roll shack and over the Sheepscot River, past the peninsula turn-offs for Newcastle, Damariscotta, Waldoboro, Friendship.

“Probably the Lipshitz chapter,” I said, staring out the window. She looked over at me. “Because, you know, it ends with cooking Italian food. Everybody understands Italian food. Right?”

“Sure, Honey,” she said. “Whatever you think.”

“Sure, Honey,” she said. “Whatever you think.”

During the last half-hour of our ride to Rockport, I began to worry: this was the very thing that my publisher had fretted over. No one would know what the word treyf meant outside of New York City. It hasn’t yet been dragged into the Yiddish-English lexicon, like schlep and schmuck and yutz and putz. No one at the reading would see the cover image of a three-year-old me sitting on the lap of the 1965 Macy’s Santa and get the joke. I would have to go into great and exhaustive detail about Halachic law, and mixing milk and meat, and cloven hooves, and fish without scales. I would complicate things even further by explaining that treyf can also mean unclean, unacceptable, forbidden. That it contains within it a tinge of exclusion, of being on the outside looking in, of assimilation.

And then, for good measure, I was going to read a chapter involving a Hasidic rabbi named Lipshitz who tried to get me evicted from my long-dead bubbe’s rent-controlled Brooklyn apartment building where he was the superintendent, and where I had moved in 1990 after a bad breakup.

With a woman.

And this, I realized, is the thing that no one ever much talks about while one is in the throes of writing a book that is hard-wired to a particular community and particular sensibility: Will it appeal beyond its obvious audience? Will it make sense? Will it require great and intensive explanation that will ultimately uncoil its narrative timing and humor and insight? Should writers, while we are working, allow ourselves to become distracted by the fear that no one beyond our immediate world will understand what we the hell we’re talking about?

On the face of it, the answer is no. Writers have, since the beginning of time, written what they know and what they live, in their own culture’s vernacular, without the hobbling concern that others simply won’t get it. They’ve had to: the Joe Kavaliers, Dilsey Gibsons, Rabbit Angstroms, Joe Many-Horses, and Codi Nolines of the world depended on their creators to write them unflinchingly, unapologetically, without cultural explanation. But put to the hard test — at events, readings, signings — where we come face-to-face with an audience of readers to whom we and our characters may be utterly alien, things become a little bit more complicated. In my experience, readerly kindness and compassion and an unflagging, almost dire interest in the human condition win out, every time.

My audience in pristine Rockport Maine didn’t flinch when I read about Lipshitz-the-Goniff, and how he and I were outsiders in the worlds in which we landed: both of us, treyf, both of us trying to find our way in a universe that isn’t always kind. When the reading was over, an older Mainer came over and silently touched my elbow — the Down East signal for I’d like to have a word with you.

We stepped away from the throng and she grabbed my hand.

“The thing about it is,” she said, “Treyf is about all of us. We are all on the outside, looking in. Every last one of us. Thank you so much.”

I thanked her, this beautiful older lady with the silver pageboy and the bright blue eyes who, with one line, confirmed my belief: we are far more alike than we are different.

Elissa Altman is a food and cookbook editor and the writer behind PoorMansFeast.com, winner of the 2012 James Beard Award for an Individual Food Blog and the foundation for her previous book, Poor Man’s Feast: A Love Story of Comfort, Desire, and the Art of Simple Cooking.

Related Content:

Elissa Altman writes PoorMansFeast.com, winner of the 2012 James Beard Award for Individual Food Blog. A food and cookbook editor and writer, her work has appeared in Saveur and The New York Times, on Gilt Taste and The Huffington Post, and has twice been selected for inclusion in Best Food Writing. She lives in Connecticut with Susan Turner and a small herd of animals.